|

Rated R for some pretty brutal imagery. Candyman has always been one of those horror movies that bled out of Clive Barker's imagination. Barker was always known for the visceral more than the actual storytelling. While this Candyman tells the story with the best of them, the notion of hooks murdering folks is still very present. I will say that DaCosta milks the off-screen kills, which seem far more brutal than they actually are. There's also some sexual content, but that's pretty minor when people are getting killed by hook. R.

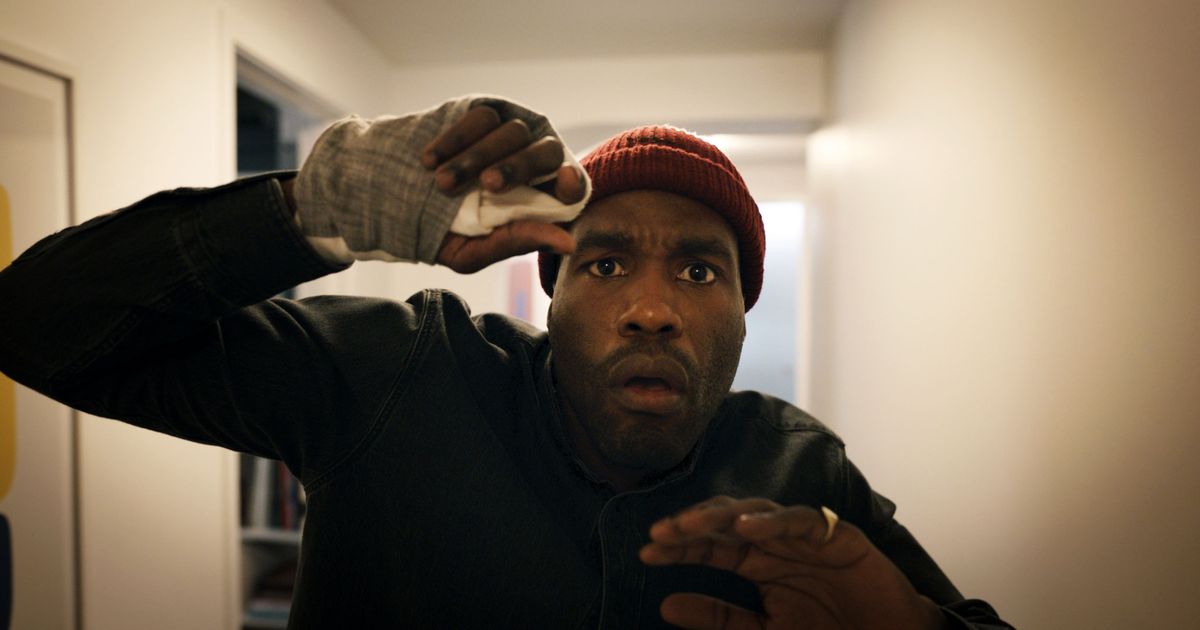

DIRECTOR: Nia DaCosta See? I told you! I told you that the first movie was underbaked and that there was something there! The first Candyman was a watch to prepare myself for Nia DaCosta's sequel. I am so glad I watched it. I mean, I broke one of my own unwritten rules to watch this Candyman movie right now. Normally, if a new movie is going to come out, I'll binge the entire franchise before watching the new film, regardless of how stand-alone the film is. But no one ever talks about Candyman 2 or 3. Also, I went to the library and this was on the Lucky Day shelf. (The Lucky Day shelf are books and movies that have a long wait on hold for them, but they have some copies that just happen to be in that aren't being reserved.) So I told myself to chill out and just watch the movie that I wanted to see. Maybe one day I'll knock out the two sequels that I just passed by, but it might be a little bit unlikely. The first film was a film made by a white man starring a white woman about the plight of Black people. It felt like tourism to me. There was this vibe that only white audiences spend big bucks on movies, so they put Virginia Madsen in the leading role, despite the fact that this was a narrative about the oppression of Black people in lower income communities. Despite my reservations about the movie, there was something at the core of the film that really spoke to something beyond the horror genre, something pretty rare to find in 1992. It was Jordan Peele who decided that horror movies need to be less obtuse when it comes to finding a message in the story. Horror movies offered filmmakers opportunities to criticize and satire society in a scathing way and nothing really changed the horror genre more than Get Out. When I found out that Jordan Peele was attached to a Candyman reboot / soft sequel, I thought it was genius. Sure, I hadn't seen the first Candyman because I'm a hypocrite who is actively trying to be anti-racist now. But I knew Candyman's reputation. It was Black horror to me, which always seemed more intense and less jokey than the horror that I had experienced in my adolescence. But once I had watched the OG Candyman, I had hoped that Peele would bring his experience to the franchise. But I keep calling this movie Peele's film. A lot of that comes from the fact that it feels like a Jordan Peele movie. But really, this is Nia DaCosta's baby. There's a visual style here that is accusatory while being unabashedly artistic at the same time. What DaCosta did with this film is remove all of the ambiguity from the message. With the OG Candyman, which I seem to be holding in more and more disdain the more I write, it wanted to take this really broad stroke at the idea of racism. Racism was something of the past that simply existed today. The eponymous villain was a slave. What happened to him happened in the past and that affected the world of academia today. Yeah, I love that a lot. But it also lacked the nuance of what was really going on in lower income communities. It only hinted at police abuse. It didn't straight up condemn the notion of liberal tourism. But DaCosta's film, in its origin story especially, attacks the notion that slavery was a thing of the past. The Candyman in DaCosta's film is not one man. Instead, the Candyman is a history of violence from 1890 to the present. Every Black man who was abused by the system and tortured in a specific manner became the Candyman. It becomes this hive mind, making the imagery of bees all that more appropriate given the message of the movie. It's absolutely brilliant. Coupled with this haunting shadow imagery, the story genuinely gets scary. There's a line. I've heard it in other works and in other contexts. "They love what we make. They hate us." The line is referring to white people and the consumption of Black art. I know that I'm on trial with this comment. After all, here I am, a few days before Christmas, reveling in my wonderful suburban home and writing about the plight of the Black man in cinema. Candyman, with both versions, really points a finger or a hook at academia. The notion that a blog would try to unpack a horror movie of this scope is almost forcing me to say his name five times because I'm tempting fate. (I didn't realize that the analogy would work so well before I wrote it, but now I'm just finishing writing because I've written so much up to this point!) DaCosta's version of the film really attacks law enforcement for their shoot-first, ask-questions-never attitude. But the film isn't about a police officer. I don't know that a single officer gets a name in this movie even. But it does torture an artist, a savant out of grad school. He was the child in the first movie, a haunting if unnecessary nod to the original film. But the moral crime that brings him to the Candyman's attention is the academic response that Anthony McCoy has to a brutal story as he enjoys the benefits of his gentrified neighborhood. McCoy almost gets a pass --despite the fact that he was actually baited to invoking the Candyman's name by William Burke, who interests me more than most antagonists. Because he is a Black artist, the movie isn't as damning towards him, despite the fact that the movie ends with his mutilation and eternal damnation. He does receive barbs, stating that artists are the first wave of gentrification. But Anthony seems to be in that position of both exploiting the fruits of tragedy and meaning well from an intellectual perspective. The movie's end, with Anthony becoming this generation's Candyman, is a little muddy. I love it from an emotional perspective. It's very creepy, watching him being built into this new Golem for Cabrini-Green. But it also doesn't make as much sense as it should. In terms of emotional justice being served, Anthony broke some of the cinema sins that basically locked him into an awful sense of karma. He needed something terrible to happen to him. He did evoke Candyman's name, despite the warnings not to. But even worse, when people started dying around his artwork, he did elicit a sense of sympathy to those who had died. Instead, he only saw the value of press surrounding his work. But there's a missing beat in there somewhere. I was going to post this as a perfect score on Letterboxd, but that might be a bit of a flaw in the film. Still, I don't know where the low ratings come from. Part of me believes that there are always going to be naysayers when it comes to revitalizing a franchise. But I think that this Candyman is smarter and more impactful than the original. It's a powerhouse that is scary in all of the right places. And as much as the movie is a sledgehammer, there's something really fun and haunting about the film that I can't ever complain about. I'm sure that I might have just been in the perfect headspace, but I won't apologize for really liking the movie.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Film is great. It can challenge us. It can entertain us. It can puzzle us. It can awaken us.

AuthorMr. H has watched an upsetting amount of movies. They bring him a level of joy that few things have achieved. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed