|

PG, and for really weird reasons. Like, I totally agree. This movie should not be G rated, but I don't think I've ever written, "because the parents are terrible people." Like, the entire movie is about intentional child endangerment, leading to the kids planning horrible death traps for their kids. This is Tim Burton movie with a better color scheme. There's a lot of talk about wanting to be orphans. There's constant risk to children. There's also probably the odd concept that kids should rebel against their parents, which I can't have around my house. PG.

DIRECTORS: Kris Pearn, Cory Evans, and Rob Lodermeier It's my wife's birthday. Today has consisted of me getting early morning pancakes, giving my wife her birthday gifts, and then getting a filling. Her goal today is to relax and do puzzles in her book. I was sitting down, eager to read my book (The Dark Tower VI: Song of Susannah) and then remembered, "Oh, it's Friday, not Saturday. You need to write.) That's fine. The Willoughbys was the biggest surprise pick. I couldn't get the Amazon Fire Stick to work on the outdoor projector for some reason, so we had to rely on old Netflix for a movie. (Netflix and Hulu work on our Blu-Ray player and nothing else is worth our time out there.) For a surprise movie, it was pretty excellent. Part of me was terrified to see this movie. I watched the trailer on Facebook for the movie, and then I discovered it was a movie about a bunch of kids trying to kill their parents. The whole children-trying-to-get-rid-of-guardians thing is becoming a worrisome trend in our house. My daughter is low-key obsessed with A Series of Unfortunate Events and I'm just starting to take the hint. That trailer made it seem like they were just a bunch of kids trying to bump off their parents. Thank the Lord that it is far more than that. Again, like Count Olaf, the parents are horrible human beings that actively loathe their children. The movie presents these parents as comically bad parents. They are almost unaware that their children exist. And the kids aren't trying to kill their parents. They're just trying to get their parents to abandon them, which is somehow better? Listen, I didn't want to show my kids this movie and now I have. I can probably live with that. It ended up being a slightly darker movie than they normally watch, but overall, it was fine. The thing that sold us? The vocal cast. There's a lot of great actors in this movie and we tend to turn a blind eye to what's good for our kids if we want to see the movie overall. I find the movie's message kind of confusing, but that's what makes this blog worth writing. Some movies aggressively defy me to write something meaningful about them, and this might be one of those movies that do so. The primary conflict in this movie rests between the protagonist, Tim, and his parents. Based on a book by Lois Lowry (which both makes sense and makes absolutely no sense), Tim has this epic heritage behind him. He feels the weight of his ancestors on his shoulders to become something impressive and historic. I get it. It's a cool character trait to have. After all, we can't all be winners. But his parents stand in the way of history. Fundamentally selfish human beings, the couple is so obsessed with their love / lust (?) for one another that they place that love at the center of every decision made in the household. Now, a sane relationship based on love would understand that any children that might be the product of such a love might only expand that love. After all, I anecdotally assume that everyone has the same feelings about children that I do. Instead, the Parents Willoughby actively scorn the children and find them to be distractions from one another. Narratively, it is such a bizarre message to talk about the reason for the parents' cruelty as one that can be defined as love. These people are capable of emotion. They aren't scornful of one another; they are scornful of their children. Don't get me wrong, I often think that I just want to hang out with my wife rather than have to clean up more nonsense around the house. But there's this insane motivation behind everything that goes on in the movie. In terms of directorial success, the movie does sell the concept that this is a really bizarre reality where pretty much everything exists in a stage of absolutes. The movie never really tells us that it is a world of absolutes though. Tim is a failure because he can't grow a mustache. The parents' understanding of love is limited to one person. A candy maker adopts the first child that comes his way. A nanny is either perfect or awful. Basically, the world is one entire black-or-white fallacy, but it only makes sense if that's how it makes sense. For as bizarre as Tim's siblings and he are, they come across as fairly normal because of how the rules of this world make sense. It's actually why I appreciate the parents' reactions to being saved by the children. The end completely sells the movie for me. I mean, I had a good time throughout. There's a lot of gags that really cracked me up and I completely enjoyed. But I also am really tired of formula when it comes to kids' movies. The movie has this long setup for the theme of the movie. Tim, in all of his attempts to become an orphan, loses sight of the fact that his parents have to have some value. I was completely ready to have Tim shift focus away from being an orphan to being someone who has to keep trying. After all, for all we know, Tim is an unreliable narrator. The movie really points hard to that too. There's this implication that the parents encountering a near-death experience might give them a heavy lesson on the meaning of life and love, but that never happens. This is where I stand up and applaud because that would be way too simple. Sure, other movies might do that, but not The Willoughbys. There is this dynamic character shift in Tim where he realized that he made all kinds of mistakes. But those mistakes were the best choices in a series of terrible other options. Yeah, Tim continues to make other big mistakes, but the central mistake he made...wasn't a mistake at all? There's something really satisfying about the parents stealing the zeppelin because it just reminds us that people don't always act the way we want them to act. Trust me. This is a high point in cinema for me. But the one thing about having such bizarre rules in a movie is that we don't know what choices the characters really have. Any kind of figment of law doesn't really exist in the world of The Willoughbys. It's almost as if this is a child's interpretation of how law has to work. The candy maker is simply allowed to keep a baby, despite the fact that the factory is a super dangerous place for the baby to live. (That baby nearly dies a dozen times and that's a choice.) Social services is a kid jail. I kind of want to ruminate on that for a second. Social services and child protective services often get bad raps for making sure that kids have a safe place to sleep. But Tim is actually put inside a prison cell, which makes these characters completely unsympathetic. It's actually Maya Rudolph's Nanny character, who is ultimately a lawbreaker, who comes across as a far more sympathetic character. But she's not meant to keep those kids. The parents are still completely distant and negligent. It's all through the power of love that everything resolves itself. Trying to attach a greater meaning to this movie is a futile task. Sometimes a movie is just a cute movie. There's a narrator who admits that the story wouldn't work unless we kind of shut our brains off. Yeah, he's played by Ricky Gervais. That's pretty on the nose for me, and that's what the movie is about the entire time. There's not much depth, but it is super fun and kind of witty. Not everything, apparently, can have a deeper meaning. (Besides the fact that family is the one you make, not the one you are given. But that's cliche at this point and I refuse to write an essay on it.)

0 Comments

Rated R for language, nudity, and realistic violence. I remember that one of our teachers showed this to us in school. I don't know how. Like, at all. Now that I'm a teacher, I couldn't get permission to show this under any circumstances. I mean, I'm not even upset. This movie blew my mind and opened the world of Spike to me, but I'm floored that it happened. It's weird that I only know this because I'm a teacher. I thought, "Yeah, I could just give a permission slip." Not so much. It's a pretty brutal R when it gets to the violence. R.

DIRECTOR: Spike Lee I tend not to change up the lineup of movies I write about. I love Do the Right Thing. It's one of those few movies that I own in both DVD and Blu-ray. Okay, that might not be the best litmus test because I'm not the biggest fan of The Last Picture Show. I probably watched this a little over a week ago. You can't help but apply Do the Right Thing to the racial climate in America and how little has changed since 1989. I thought it was such a movie that should be watched in response to police brutality. I guess I shouldn't have been surprised that there's now another video of another black man being killed basically for being black. Did I pick to write about Do the Right Thing because of the events in the news? No. But I'm certainly happy to write about it because this has got to stop. I can't say that I get into every Spike movie. I really love Spike. He's one of those directors that raise my eyebrows when I hear of another project from him. Nothing has really ever moved me as much as Do the Right Thing has. I hope that's not a commentary or something on me, besides the fact that you can now pinpoint my tastes. The thing I love about Do the Right Thing is that Spike, in the course of a two-hour film, stresses both the complexities and the simplicities about race. Maybe the words "white privilege" is never officially vocalized in the film, but it explains how everyone feels like they are on the outs, but that those feelings may not reflect the reality of the situation. Mookie's block of Harlem is comprised of flawed individuals. Spike, in the shoes of Mookie, himself is the best of the flawed, with the exception of Mister Senor Love Daddy. As a pizza delivery man, he's allowed to be the avatar for the audience. He's an outside observer to every narrative running throughout the story. He's friends with everybody, but he also gets on half of his friends' nerves. Mookie works really well to show how a setting can be the most important character in the story. Yes, Mookie is the protagonist and main character of the story. But most of the goals of the story are about maintaining the status quo. Mookie is fundamentally counter-revolutionary. He's riding this really tenuous line of working for people that he both respects and loathes. Sal, for all of his talk about how Mookie is part of his own family, has some really racists attitudes. He's raising a son who is aggressively, next-level racist. And Mookie, because he needs a paycheck, must bite his tongue any time something that runs his way. He doesn't even that good of a job at that. He's this diplomat of what it means to survive. He's allowed to say "so much" before he's at risk of being jobless. Why does Radio Raheem break our hearts so? When I watched this in high school, I had no idea. No idea. I lived in a very comfortable suburban environment. I thought that this happened once in a blue moon and that Spike was commenting on that. He created this gentle giant (who's not all that gentle, but you get my point) that has very simple needs. He wants to have his music. Radio makes sense from both sides of the conflict. Radio Raheem has the right to play his music. It's not like people are sleeping and he's blasting "Fight the Power" wherever he goes. No, this is mostly in the middle of the day. His demand can be annoying, but these are one of those things that's just considered irritating rather than anything insidious. If a customer brought in Raheem's boombox while I'm trying to talk to him, I'd also be annoyed. But Sal's reaction is vitriolic. That's where the lesson is. Sal and Raheem's storylines really intersect in this place that explains the theme of the story. People want what they want. Raheem wants his music because it has the message of "Fight the Power." Sure, the song is a bop, but that also defines his identity. The song is meant to be aggressive and in your face because the message needs to be taken from it. The image above of Raheem's Love / Hate insignia reflects this attitude. Sal is incapable of making the logical leap that Raheem or Smiley have made. They come across as simpletons, talking about something that would never really affect Sal. All Sal hears is colored-people's music. He's trying to talk and someone else is co-opting his Italian identity. This is mirrored in Buggin' Out's protest about the Italians on the walls. Admittedly, Buggin' Out is probably part of the reason that Sal can't hear Raheem and his concerns regarding race, but that's another matter. Sal, in his request, isn't hearing that he's telling Raheem to stop talking about the most important thing to him. He's hearing noise and a drowning out of his Italian identity. It's probably what makes Buggin' Out so infuriating. Buggin' Out has a point. Sal's lack of colored representation on the wall is problematic. But Buggin' Out starts at a point of aggression. Buggin' Out's identity is one of confrontation without consequences. He wears that badge of martyrdom, despite the fact that it tends to be the others around him who face the consequences of that martyrdom. I really don't think that Buggin' Out really cares about the imagery on the wall. Instead, he likes the attention that he gets by saying that he's morally outraged by the pictures on the wall. He also knows Sal's buttons. Sal's core goal is honoring his culture. But he also, when not provoked, has a love for the community. Pino doesn't understand that love. Pino, as a foil for Sal, works wonders because it forces Sal to audibly confirm why he stays in this neighborhood. Remember, this is a day that started with Buggin' Out starting a protest of his shop, yet Sal talks about his love for his customers and his community, which falls on Pino's cultural deafness. Yes, Sal is a racist, but he's in a spot where something can be done about it. I don't want to make Sal a Christ figure, despite his sacrifice at the end. But his sons represent the good and bad thieves. They are both tugging on Sal in certain directions. But again, Sal is not Christ. He has NONE of the answers. He's just a guy who is in this place of potential movement. The riot makes the movie. It's a very good movie up to that point. It's a great movie from that point on. I said that Spike complicates the discussion about race throughout the story. In the riot scene, he simplifies it. It's the face of the police officer with his baton on Radio Raheem's neck that strips away all pretension of what people think race is. There's a scene before that where representatives of every ethnicity talk to the camera and say what they think of another race. It's hate filled anger that is in the subconscious of all of the characters, and by proxy, in the back of all of our thought processes. But there's a moment where we all kind of get together when Raheem is being choked. Radio Raheem died because he was a black man. The police officer probably defended the choice because Raheem was a giant. But there's a moment where everyone just stares at the offending police officer. Raheem was done fighting. He was incapable of running or of fighting. Yet, he collapses to the ground, dead. Buggin' Out, in victim fashion, adorns himself with Raheem's sacrifice and the city explodes. The heat wave that covers the city has that explosion that we knew was coming. And it's Mookie who destroys Sal's. Mookie destroying Sal's raises so many questions. I need to learn to distance myself and realize that it's not just one reason that Mookie throws the trash can. Mookie is us. Spike playing Mookie is no accident. If the song throughout the movie is "Fight the Power", a second-person imperative, Spike as Mookie is no accident. We are the ones meant to fight the power and to take to action. He's someone who respects Sal more than his peers, and he's the one to diffuse the tension with violence. That image of MLK and Malcolm X that Smiley continues to show the audience is the reminder of the complexity of nonviolent response. I will always preach nonviolence, but it is eternally frustrating when one side will continue to use violence to push an agenda and that they get away with it. Those quotes at the end offer no solution to a complex problem. But Mookie throwing that trash can in the window probably saved lives. Rather than killing Sal and his boys, Mookie takes something that can be replaced. Sal can't see that. The building is a child to him. Mookie's right: Sal is going to get a sweet insurance payout and ride again. We know this happens because Mookie appears in other Spike Lee joints. But Sal is also right. That building was made by him. Any amount of money can't replace the work that went into decades of service towards the community. There is no right answer. It's the story of reality. There are people who abuse their role as police officers that we can't touch. This week, it is George Floyd who proved that. But we can hurt each other pretty easily. Because there is no easy for us, there's no easy answer for the movie either. Spike presents two seemingly paradoxical philosophies by MLK and Malcolm X. He talks about the value of nonviolence and the necessity for violence. The reason that Do the Right Thing keeps showing up on my favorite movies is that it doesn't offer a cookie cutter view of race relations. There are so many white knight movies that leave a bad taste in my mouth. If life was that easy, there wouldn't be an issue. But Spike presents the real problems to why race is a problem. There are people who can talk all they want and there's not going to be consequences and others who will get choked out simply because they've been associated with being intimidating. To the family and friends of George Lloyd, I'm so sorry. I see you. It's PG for being slightly crass and, for some reason, perilous action sequences. There's some pretty base humor, but that's pretty typical of the Illumination folks. Really, it's because there's some danger for some of the characters throughout the story. Nothing is all that scary, so please keep this in mind. But more sensitive kids might have a hard time with this one. It's mostly fine. PG.

DIRECTORS: Chris Renaud and Jonathan Del Var The problem when swapping choices for family movie night is that, sometimes, Dad hasn't seen the first entry in the series. Sometimes, Dad stayed home when the grandparents took the kids to see the first movie. I wouldn't minded to see the first movie. But I think I can probably state with some degree of confidence that I probably wouldn't have needed to see the first movie. I know that Louis C.K. basically can't voice a children's film anymore and that Patton Oswalt took over from him. It kind of feels like this is a new character, but I can't really attest to that. I'm assuming the last movie ended with Max's owner having a kid that he bonded with. Maybe it was about coming to terms that Max wouldn't be the most important thing in the family's life? Regardless, I think I got the gist. I just feel dirty watching a sequel without having seen the first movie. Everyone I know said it was skippable. A good writer would build to the biggest point. But I write these things every day. It's exhausting planning these things when it comes to building to a crescendo. So I want to talk about the oddest choice for this movie / the fact that filmmakers are really stuck to a formula. The Secret Life of Pets movies don't need real villains. The conceit behind these movies is that pets lead full lives outside of the view of their owners. It's a fun concept. Really, it's another Toy Story concept. Now, I don't know why I have never brought this up with up with stuff like Toy Story 4, but I'm going to really apply it to The Secret Life of Pets 2. Max has a really honest and vulnerable problem. I mean, I'm going to talk about the toxic masculinity of Rooster sometime through here, but a villain and the external conflict should somehow directly tie to the internal conflict of the story. If I had to sit down with the directors right now, I know how they would answer this: Max was afraid to do anything before, but the villain shakes him out of his little world into a much bigger world. The problem I have with that is that is a trait of "all villains". The villain isn't personal to Max or Snowball. Oddly enough, he doesn't really belong in any version of a movie about talking animals. He's almost in his own story that doesn't match. Listen, Kevin Hart is hilarious. I learned this from Jumanji: The Next Level. The man might be a genius and I'm the last person to discover that. But they wanted to give Snowball some things to do that would break the confinements of the conceit. That's a real problem because Snowball learns nothing over the course of the story. Snowball's central drive to the story is to become a superhero. However, his major problem getting in the way of that goal is his own ego. It's weird how that conflict really works for a story like The Secret Life of Pets. Snowball is so obsessed with becoming a famous superhero that he kind of acts like a jerk to the other pets. Instead of having Snowball coming to the realization that removing his ego from the equation means that he could do some real good, they put Snowball into a comic book level action story. Snowball fights Sergei, which is a pretty lazy voice for Nick Kroll by this point, which doesn't really teach Snowball anything. It actually is a conceit breaking story because it is about how human-like animals are when we aren't looking at them. Having a villain is possibly the worst thing that this movie could have done. It really tears at the idea that humans have no idea what animals are doing. Over the course of the film, Snowball actually frees a circus tiger. The movie even jokes with the idea that Snowball has no idea what to do with this giant tiger. But the movie doesn't really do a good job even responding to that. It writes off the idea that an old lady wouldn't notice the difference between a billion cats and a tiger. But that tiger wrecks things everywhere he goes. That joke undoes a lot of the other jokes. You know, the ones where human explain away absolutely insane behaviors? Then, it brings Max into that storyline? There's a scene where Max is fighting wolves on a train and he uncouples train cars to distance himself from the scary wolves. Why is this scene in here? The animals have to show that they are smarter than Sergei to take him down. It's breaking the rules established by the premise of the film. It's called The Secret Life of Pets. I know this seems nitpicky, but I have to write a lot of words about this movie and it's the thing that stuck in my craw. I said that I would be taking about Rooster and toxic masculinity. I really don't like the story and what it is trying to say about Max and his issues. Max actually seems to be having some degree of a mental psychosis. He's got a level of anxiety that is causing him to chew on his own body, causing him physical harm. It's an excuse to have Max wear a cone for a chunk of the film, which I guess is meant to be funny? But when he meets Rooster, he gains an understanding of what it means to be a dog. A dog is supposed to be brave and self-sufficient. A dog is meant to chase away darkness and provide for a family. I think we see where I'm going with this? Rooster is a boomer. You cast Harrison Ford as this standoffish, aggressively judgmental dog who is unapproachable. Good job. You got the most on-the-nose casting out of anyone. Max seems to have real anxiety brought about by not knowing what is around him. It's so intense that it is physically manifesting. The message of Rooster's conditioning of Max is "Anxiety isn't real. Suck it up." That's a problematic story to tell kids, right? I know that the message is even more for parents, but that somehow might just make it worse. Max is concerned for his kid. Max sees himself as a parent for the kid. He's adapting to the constant changes going on around him. Instead of telling him that he's wrong for worrying, what if he got honest help? Rooster is part of the old guard, that was bred to not feel anything. Anxiety was for weak women and men were meant to be aggressive. I thought we were past this kind of storytelling? It seems like a really regressive story to tell. I have to admit: I had little desire to watch this movie. My kids picked this movie and then I mentally checked out. It's a bad thing to admit, but it is true. I didn't want to watch a sequel to a movie that I heard wasn't that good. I went into it trying not to have fun and I fulfilled that prophecy. It's not necessarily the fault of the movie. I just find it bizarre that Patton Oswalt is cool with minimizing mental illness. Again, I'm also reading pretty deep. Also, does Patton hate Louis C.K. now? I have no idea, but it's interesting to read complex relationships based on projects that people are attached to. I'm sure this movie is better than I'm giving it credit for. Regardless, meh. Rated R for intense sexuality and some pretty messed up gore at one point. There's language, but basically this is a movie about people treating each other like dirt in a place in America that is reminiscent of a Fallout video game. There is nudity throughout, so not much is left to the imagination. Just because it's monochromatic doesn't mean it can't have intense content. R.

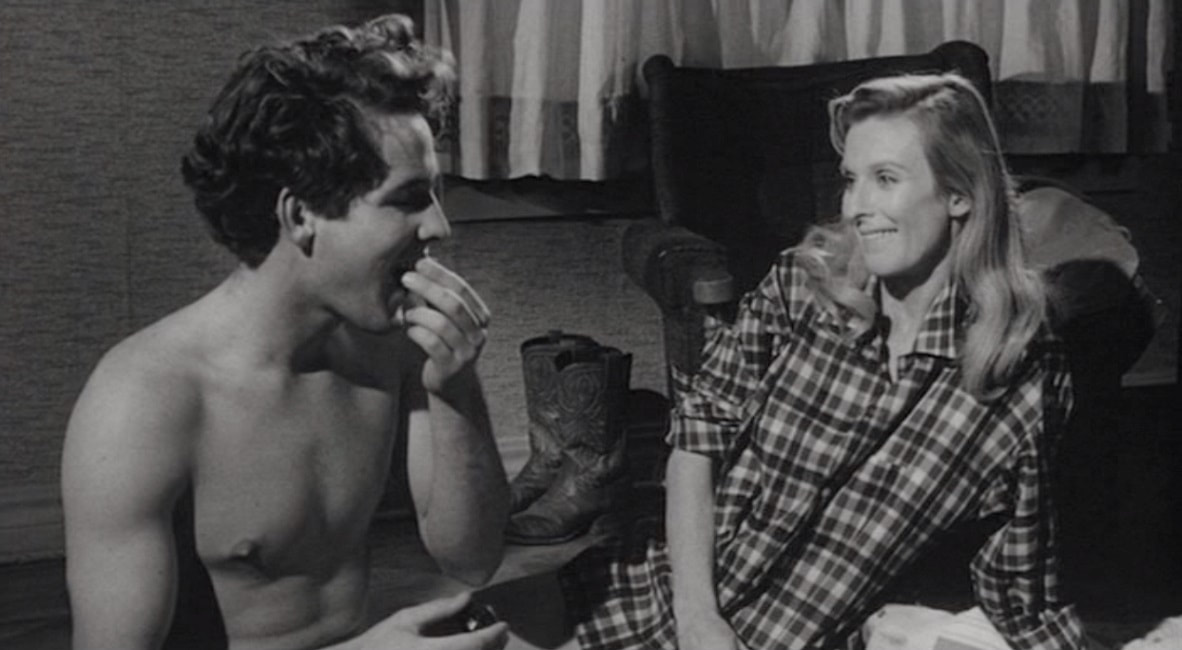

DIRECTOR: Peter Bogdonovich I owned this on DVD for a long time and I watched it the first time I got it. I'm burning through the BBS Criterion box, and guess what is in that collection? So now I've watched The Last Picture Show twice in my life, both times watching a copy that will only be watched once. I'm putting it out there, I get why people like The Last Picture Show. I just don't love it. The Last Picture Show is entering the specific subcategory of film that both waxes nostalgic and comments on the problems of its era. I'm looking at movies like Dazed and Confused and American Graffiti. Bogdonovich seems to set this movie in an era that seems to evoke his own dark adolescence, which is troubling the more you think about it. The world of The Last Picture Show is one fundamentally built on selfishness. I can't give this an absolute characteristic. After all, this is a world where Sam the Lion exists and he seems to be a pretty good dude. But ultimately, most of these characters seem to be focused on the self. Bogdonovich, like Lucas in American Graffiti, focuses his camera on teenagers. Perhaps a lot of their selfishness derives from the fact that they are teenagers in a state of arrested development. These are teenagers right out of high school. The setting of Picture Show is a town that expects high school graduation and then immediate work in the mines. There's not really this attitude of success. There is no real growth for everyone and the entire town is a stark and physical reminder of how the cycle keeps repeating. I can't help but think that the sexuality in this movie is almost animalistic. Bogdonovich uses sexuality as both primal and as currency. Sonny is rejected at the beginning of the film because he wants to have sex before marriage. His girlfriend, on the other end, doesn't really understand the intrinsic value of marriage. Sex is what traps men in a marriage and there is no value to a marriage otherwise. While this is an overly simplified idea of what sex and marriage are, Jacy and her more updated concepts on sex is also ultimately silly. Jacy, on one hand, says that she would never repeat the mistakes that her mother made. She echoes the sentiments on marriage from the beginning of the film, but is entering this period of self-discovery which she, at first, finds liberating. That exploration, however, quickly becomes toxic. Jacy's first moment of vulnerability is one where she is being used and nothing is reciprocal. She starts the film in a place of confusion and frustration about what is expected of her. All of these moments will lead to Jacy's being used by her mother's boyfriend. Jacy perhaps has the clearest throughline, but the movie is fundamentally about Sonny. I know that Jacy gets mixed up in that narrative, which leads to Sonny almost losing an eye. Sonny is such a bleak commentary. He's the hero of the story. He actually seems to care about people around him, unlike Jacy or Duane. But Sonny is still pulled by his own selfishness. He gets entwined with Ruth not because she's that sexually attractive. The leading drive to be in a relationship with Ruth is pity. He sees this woman who is neglected and abused by her husband in a small town that couldn't give a fig about its inhabitants. He seems to actually be the best version of himself when he's sleeping with another man's wife. That level of irony is telling. He's actually the bad guy when he stops Ruth from cheating on her husband. But that's because of motivation. He's with Ruth because he sees her humanity and, subsequently, that humanity being stripped from her. But he doesn't leave Ruth because he realizes that Ruth shouldn't be cheating on her husband. Rather, he trades Ruth for the younger model. On a conscious level, Sonny is with Ruth because he senses her humanity. But on an unconscious level, he's with her because she's absolutely forbidden. Ruth is not only another man's wife, but she's also taboo because of the age difference. When his relationship with Ruth becomes acceptable, he then shifts his relationship to Jacy. While age wise, Jacy is perfect for Sonny, it's her status as Duane's ex-girlfriend and town harlot that attracts him. It's the idea that he's hurting Ruth with this choice to choose the younger model that pushes him towards her. Sonny never really views himself as the bad guy. But he's also a guy who is lost to his baser instincts. It's why he never really understands his marriage with Jacy. Jacy, compared to Sonny, is more in tune with what she's actually looking for. When Sonny is forbidden, the idea to get married is sexy and exciting. When Sonny counters with vulnerability, she's mortified by her actions. When there is a scenario where people might accept their decision, the marriage is a dumb idea. I love how that marriage never really comes into play. Listen, I write a film blog. I talk about movies every day. I know that if I was directing a movie, I would tie cinema into my own movie. It's tempting as heck. But centering the film around something that is clearly at least parallel to Bogdanovich's sense of nostalgia is a bit forced. The cinema is the last thing in the town to really go. It is near Billy's death. It's this whole idea that the era of The Last Picture Show is the last generation to survive in this small little town. But the cinema, as much as I emotionally understand that decision, is an odd commentary on the death of the town. Listen, the cinema represents the only arts hub in this town that is only known for a pool hall and a diner. But is The Last Picture Show a really call to the rise of the arts to free the soul? It's an idea that could really resonate in this story. But the movie theater was a place to meet with your girl and get a thing of popcorn. It's not like Sonny found something inside himself to become a better person because of his experience with the picture show. Really, the biggest thing that the picture show does for the movie is establish a time period and a sense of nostalgia for Bogdonovich himself. It just wants to have this deeper connection to the film that really isn't there. Honestly, I'm more moved by Sam the Lion. The death of Billy might be the actual climax of the film. As much as I want the close of the picture show to be the emotionally important climax of the film, it's the death of Billy that wakes Sonny to his disgusting behavior. Billy is the one good thing in their group of friends. When they try to force Billy into a sexual act, Sonny feels genuine guilt, which is why he's forgiven by Sam. The image of him sweeping dirt during a sandstorm might be the most on-the-nose metaphor ever. I won't lie. I stare at the setting of The Last Picture Show and I just want to clean and fix everything. But that's what Billy is doing in the street is what I want to do to the pool hall. Billy is trying, possibly by the fact that he's considered simple by the town, to fix what can't be fixed. But that's why Billy's death is the most important thing that wakes up Sonny. Billy was never going to fix the town. But he enjoyed trying. Sonny sees the personification of goodness die and then he sees his own selfishness because of it. It's a heavy movie, but it also is remarkably bleak. I don't really ever want to watch The Last Picture Show. It is long. It makes sexuality remarkably uncomfortable. There's nothing fun about The Last Picture Show. It's just bleak misery for long periods of time. Rated PG for mild things. I mean, it's a little kid who hangs out with an imaginary polar bear. But the movie never presents the polar bear as imaginary. It's an extremely tame movie for the most part, but Timmy's unique perspective leaves a lot of the movie to be interpreted for oneself. If you squint, you could find some questionable content, but it's a well-earned PG rating. It's a Disney+ movie, so take from that what you will.

DIRECTOR: Tom McCarthy I broke my own rule. It wasn't for very long, but it did happen. I fell asleep during this movie. It's not even bad. I went from falling asleep in the movie to immediately preaching the movie. Like, I heavily recommend this film for families because I guffawed a few times. There's nothing really annoying about it. But I also fell asleep. I'm getting up there in age. Watching a bunch of films with a critical eye is actually kind of a chore, especially in quarantine where there are so many kids' movies. But it did happen. And I'm terribly sorry about that. Timmy Failure is the first kids movie that explains absolutely nothing. For as simple as the movie is, I kept on wondering what was going on in the subtext, which ultimately seems superficial. It's actually putting the onus on me. I'm rarely this vulnerable when I'm writing these things. Normally, I have a complicated movie where I'm entirely allowed to have a poor interpretation. But Timmy Failure? If I mess this up, I'll be a regular Timmy Failure. I'm dancing around this, but is Timmy Failure: Mistakes Were Made a child-friendly exploration of a protagonist on the spectrum? Timmy sees the world in an aggressively personal way. Timmy, with his lack of smiles and happiness behind this whimsical adventures, dares me to call him out on something. The movie never drops the word "autism" or anything similar. But Timmy's unique point of view is what makes the movie what it is. He lives in a version of Portland that is larger than life, but everyone else doesn't possibly see. Timmy, as the protagonist, demands that we play along or else the story doesn't make sense. It's this bizarre duality that the movie presents. Let's use Total, his polar bear, as an example. Similar to the way that Bill Waterston's Calvin and Hobbes has Hobbes as a character that no one questions, Timmy's relationship with Total is never really explained. The movie even presents an origin to Total, but that origin is insanely bizarre. It's really weird when you are trying to establish the world of Timmy Failure. The movie presents almost a heightened reality that we have to question over and over again. It's not insane that a kids' movie presents animals acting in strange ways. But instead, there are cues for the adults watching the movie to question Timmy as a reliable narrator. And any time that we question Timmy, we come across as the villain. Timmy has this running thread of Timmy trying to get the school to be more accessible to polar bears. He logically presents this concept that there's this backwards thinking behind the school, but none of the students really point out that there has never been a need for a pro-polar bear rule in the school. This is between the adults and children involved. Adults are frustrated with Timmy, to be sure. But there is this tolerance for Timmy's behavior that makes him a unique protagonist. The goal is that we don't want Timmy to change because it is unfair for Timmy to change. Instead, we see someone on the spectrum not as pitiable, but relatable. It's kind of genius in its own way. We're so used to seeing people with various disorders as characters to be pitied. Instead, we have to follow Timmy's train of logic and want for him to be the protagonist of an adventure rather than a drama. There's not really this thread of pity, but rather of adventure. For kids, they get this story where Timmy and Total are taking on the Russians and trying to find the Segway. But for the adults, there's this split in focus. For part of the movie, we relate to the single mother raising a kid who is incredibly frustrating. That's not a commentary on Timmy. But she is fighting this uphill battle of getting a kid who may be incapable of normality. It's bad enough that she's raising a kid alone in a world where it's implied that Timmy's father left them when Timmy was young, but she has a kid who is on the verge of failure because he can't understand that he needs to meet social cues. Then we have Craig Robinson's therapist character, who completely sympathizes with Timmy. He meets him halfway and does all he can to give him cues in ways that Timmy can understand. And then, and this is my favorite character to relate to, is meter maid Crispin. He's entering a world that is extremely overwhelming and he's trying to make the right decisions when there are so many issues that Timmy's family is dealing with. He's this extremely charismatic character who keeps making realistic mistakes. The movie starts with this climactic moment where Timmy drives a truck into his teacher's house. Told through flashback, it's believed that everything that we're seeing leads to Timmy driving a truck into the house. But it's not even real. As frustrating as that is, it is also central to what the story discusses. Timmy doesn't live life in reality. He's a guy who really believes his own imagination to make his narrative progress. It seems like it is a cop out that Timmy never actually drives through a house. But that moment is actually important for Timmy's character as a whole. It is the one moment where Timmy can emotionally distance himself from his imagination. It's actually pretty touching thinking about Timmy making baby steps in the right direction. And that's what the movie, for adults, is all about. It's seeing this sympathetic character never really suffering for his delusions. He gets mad at adults for not understanding what it is like to be him. But it is also a story about a kid learning to say sorry. It's right there, in the title. It's Timmy coming to the realization that his world is not everybody's world. We never get angry at him for not understanding that. Instead, the movie is celebration of the baby steps that Timmy makes in trying to defend a comfort zone. It's not a beautiful movie. Instead, it is a fun movie that just happens to be important at times. Do I wish I hadn't fallen asleep? Sure. But it's a good movie for family night. There might be some conversations that have to happen while watching it. But our kids were cool with this being the way that Timmy saw everyday life. It's a solid movie that's a pretty strong quarantine stream. Enjoy! PG, but as always, James Bond PG. It's not a real PG. It still has a Maurice Binder opening credit sequence, which I feel is accidentally more tame. Regardless, James Bond is still an ultraviolent sex-crazed alcoholic. People die. Someone dies by fish hook to the neck in this one. Someone gets chopped up in an industrial strength fan blade. There's one murder that is so basic, but it comes across as kind of brutal despite its simplicity. It's PG, but 1985 James Bond PG. I don't think we get a PG-13 James Bond until Pierce Brosnan.

DIRECTOR: John Glen I'm not sure which Bond got me stuck longer: Connery or Moore. I think there was a big gap between On Her Majesty's Secret Service and Diamonds are Forever. I watch movies way too systematically. I don't want to go on a binge unless there's some kind of deadline to watch all of the movies before hand. I did that with the Marvel movies going into Avengers: Infinity War. But now I try spreading a franchise out a bit with lots of other movies in that list. But I'm done with the Roger Moore era, and in a way, the end of truly classic Bond. The Dalton era, in my mind, is a liminal period between the truly classic formulaic Bond and the Bond of the contemporary era. I would love to say that A View to a Kill represented the end of Ian Fleming's Bond and the Bond that we're more used to in the Daniel Craig reboot films. (I watched a horrendously long video trying to tie all of the Bond movies into the same character, including the reboot films, and it just completely fails with trying to tie Octopussy and A View to a Kill into the same universe.) It's such a weird way to close up the era of classic Bond because it isn't really all that important of a story. As much as I love the idea of Christopher Walken, Max Zorin represents one of the more one-off bad guys of the franchise. He has no personal ties. The movie tries tying in all of this Cold War mythology into the character, but it is just an excuse to get General Gogol into the film. Really, Zorin is almost a fan-fiction level mess as a background. Roger Moore is getting up there in age by this point. He's slightly a creepy old man in this movie. (Note: if you actively fight against seeing old Roger Moore, he's actually pretty good as Bond in this one.) But he has to know it's his time. They want this ultimate villain to make a commentary about the '80s, so Max Zorin is going to be an industrialism who comments on the tech boom. Okay, conceptually not terrible. It's this great self-aware moment in film. Like how Rocky III has a robot butler, A View to a Kill has a similar looking robot. It's all because Max Zorin is a computer guy, who definitely isn't Bill Gates, despite a clunky disclaimer at the beginning of the movie. But my guess is that they wanted to be a both a movie that commented on our obsession with computers AND give us the ultimate Bond movie, so they gave Christopher Walken all of these traits that would make him the perfect villain. It doesn't. There's a line that says that he's French, but he doesn't speak with any accent. I guess that's a way to describe Christopher Walken's unique speech patterns. But there's this whole throughline of Max Zorin being the product of German eugenics programs that doesn't really come into play. He's supposed to be this super soldier that might be unstoppable. That's great, but he just seems like another rich guy with ambitions to become richer. That's why we have Grace Jones as May Day in the movie. I really wanted to have a great shot of Grace Jones as the photo for this movie. Grace Jones's May Day is one of those actually really game-changing Bond girls. I'm not saying that the character is perfect in any way, but it also starts the idea of the strong female lead. Bond movies always toyed around with the idea of the strong female lead. Honor Blackman's character in Goldfinger was perhaps the ancestor of Grace Jones's May Day, but I never really respected that character like other people do. She was a character who was easily just swayed by Bond's charms. Galore abandons her sexual preferences on a dime for charming James Bond and that's not my definition of a strong female Bond girl. Instead, May Day never really falls for Bond. There are others in the franchise, but none that really command the screen time that May Day does. May Day redeems herself morally by the end of the film, which really puts herself in the category of Bond girl, but it isn't because she's enamored by Bond. I actually get the idea that she dislikes him at the end, but hates Zorin more. Part of that comes from the fact that Grace Jones introduces the idea of sexual violence on the part of the female lead. But all this talk about Grace Jones's character really makes me quesiton Tanya Roberts's Stacey Sutton. While we wouldn't have Xenia Onatopp or Vesper Lynd without May Day, we wouldn't have Christmas Jones without Stacey Sutton. While there have been more and less capable supporting roles for women in the Bond franchise, Stacey Sutton hits an all time low (pun intended). I can't imagine that someone on set didn't see Grace Jones just crushing every scene she was in and then thought "But let's have a complete waif in this movie as well." My logic behind the whole thing, and it's me just guessing, is that the commentary from the era was part of what created Stacey Sutton. The world of Bond is so grandiose and sexy. This is a story of world-hopping. One day Bond is in India with a sexy circus troupe. In another mission, he's in Egypt with a Russian spy at his side. Stacey Sutton is an attempt to get someone real into the Bond universe. She lives in a boring house. She got screwed over by a major corporation. She has her daddy's shotgun. If we're going to give a commentary on America, it may say that we're not sexy. But we are comprised of real people. I know. It's a weird logic. The Bond movies, by this point, might actually share something in common with The Simpsons formula. Watch a Simpsons episode once they are on too long. Like, season 9 or something. They often start with the following: a character --more than likely Homer --is involved in a random event that will have nothing to do with the main plot. Through happenstance at this random event, he stumbles across the main plot. A View to a Kill opens with Bond actually kind of on task. This is one of those rare pre-credit sequences that apparently has a direct tie to the main storyline. But it actually kind of abandons the main piece of evidence into studying Zorin and trades it in for the fact that Bond starts investigating how Zorin keeps winning horse races. And then the movie really doubles down on the horse race element for a good chunk of the film. It's really weird that the horse race thing matters at all. It's super confusing because we're there investigating if Zorin is making defensive technology for the Russians. But so much of the movie is devoted to this horse sale. The James St. John Smythe part of the film is actually baffling because so many of Zorin's deals leave evidence at what should be an unrelated element of the film. This seems to be a trend to this era of Bond storylines. It's not the actual crimes that are garnering attention. It's the villain's fragile ego that gets the better of them. Octopussy had the sale of gems. Moonraker had the public apology that Bond needed to make. If you are going to blow up a chunk of the world, maybe lay low for a few weeks. Don't do anything illegal. Give no reason to be investigated. Honestly, at one point in the film, MI6, the KGB, and the CIA are all investigating Zorin's oil pipelines and a lot of it comes from the idea that Zorin is acting super sketch all the time. Also, Bond be having too many secret identities in this one. I do appreciate "James Stock from the London Financial Times." (Stocks and Bonds? Get it?) A View to a Kill might be the silliest Bond movie that I enjoy. This is about as far as I'm allowed to stretch. It firmly falls into the category of "this isn't a good movie, but I really enjoy it." While I'm watching the film, my brain is telling me "this is dumb." But as a whole experience, it really works. Perhaps the fact that it is unapologetically over-the-top or maybe it is because it feels like it is giving an older Bond one last trip out before hanging up his PPK holster, but A View to a Kill is fun. I mean, the fire truck might not work as a chase as well as I want it to, but that Paris sequence. I can't stress enough that Bond chases an assassin who skydives off the Eiffel Tower by hopping on top of the elevator. He then steals a cab, which he rides downstairs. He loses the roof of his car, launches it on top of a bus, loses the back of the car and then hops onto a boat. There's a lot of too much there. But it also perfectly defines the best elements of the Moore era. Yeah, it's a dumb film. But it also is a really fun movie. You know, besides the mass murder. Passed. It's The Parent Trap. I mean, it's mostly innocent. But, like, it also is about a failed marriage where both parents agreed to abandon one of their children forever. That's a thing that the movie really dances around. The entire conceit is a giant lie to children where they don't know that they actually have a sibling? That's insane. Sure, there's no language or violence, but the morality is pretty darned dubious if you ask me. Also, we see Hailey Mills's underwear kind of.

DIRECTOR: David Swift I don't think I've seen this movie before. I mean, I knew every beat throughout the film, but I've never officially seen it before...I think. Maybe I have. Think of all the kids movies you've probably seen and forgotten. Regardless, this is one of the movies that was near and dear to my wife's heart, so she picked it for family movie night. (Which isn't happening as much as it used to when we thought that Covid-19 was going to be a three week thing.) Regardless, I'm pretty flabbergasted about the whole thing. It's the cynical part of me. The part that is broken kept on giving my wife the eyes regarding this. (Not those eyes. No, the "are you seeing what I'm seeing?" eyes.) I always knew what The Parent Trap was. I think we all basically get the concept. Well, except my six-year-old son who keeps waiting for real traps to catch people. I don't disagree with him. That WOULD make the movie better. But shy of actually capturing adults, does no one want to talk about how this movie really ducks and dodges the concept of divorce. I was born in 1983. Nobody likes my generation. I'm too old to be young; I'm too young to be old. The extremes out there find me to be a waste of space. But being born 1983 means that the word "divorce" was a fairly common topic in storytelling. It was a bummer, but it was there. But 1961 didn't really just throw the word "divorce" around, especially in a Disney movie. It's also something we don't really have conversations with our kids about. It's not a taboo word, but we just haven't really had the sit-down talk. I think Disney probably had the same concept. They didn't want to open kids' eyes about the normality of divorce, but it doesn't mean that I didn't think about it really loudly. There's slightly something unfair about the whole concept. I know. I'm a big stick in the mud. I had better rename this whole blog: "Literally, but Figuratively, a Big Stick in the Mud" because that's all I ever do. But the message of the movie really is that parents can fall back in love if they just hang out enough. Geez, there's some really dicey stuff going on in this movie that kind of teaches kids that it is on them to put their parents back together. The movie does a swell enough job of showing that Charles and Maggie really have a hard time being in the same room together. It really sells that well. Those two, oh boy! They go at it like alley cats. (I've been watching too much old timey Disney and it's affecting the way I write.) But the twins are persistent. They keep pushing for the parents to get back together...and they do. They totally do. Does no one else see the problem with this message, especially for divorced children? If you keep pushing and pushing and pushing, your parents, regardless of the toxicity of their marriage and their problems, will get back together. That's pretty uncomfortable. The more I think about it, the ickier it gets. I don't think that my wife has these thoughts. She loves love and I wish I could be that. I wish that's how I processed. But it isn't and I don't. It's really weird that there's a bad guy in the story. I think I said the same thing about The Love Bug because it seems really shoehorned into the whole affair. In either incarnation, Hailey MIlls has to get rid of Vicky. Vicky is bad news. The thing is...Vicky isn't that bad in her first encounter with the audience. She's a girl who happens to like Charles and wants to start a family. But like a lot of Disney, thy have to evil her up. Do you know why that is? It's because reality is far more complicated than this movie really allows. Vicky as a good person means that the twins have to torture someone that is inherently good. It's the problem that a lot of rom-coms have. They have characters that aren't exactly evil that have to disappear. There are two choices when this happens. 1) Let's make them evil. This is the route that The Parent Trap took and I guess it works better than the second option, which is 2) make this person a plot device who totally understands the greater good in this scenario. Yeah, I'll take evil Vicky any day because it at least justifies the cruelty that Susan and Sharon thrust upon this woman. But it is a bit silly that she's in it for the McKendrick fortune. The Macguffin of the movie takes a movie that really tries to ride the line between reality and fantasy and drives it pretty hard into the world of fantasy. Vicky chasing after Charles's fortune is a non-issue for all of the characters except for Vicky and her mother. Her mother, by the way, is probably one the things that really makes this a Disney movie because she's kindred spirits with the rest of the Disney henchmen. Charles seems rich, but the twins aren't defined by their fortune. It is really weird that Hailey Mills adopts a posh English accent for upper-crust Boston. But that's the only thing that really defines them as rich. Yet, there are apparently characters like Vicky and her mother who need to enmesh themselves into a family to get a hold of this fortune. It seems like a bit much and the story really seems to glide past the idea that Charles is almost bamboozled out of the family fortune by a complete stranger who wants to marry him immediately. I love that Vicky actively hates the girls by the end of the film, but it is only because she doesn't do well camping that crosses her off the list for marriage. The structure of the film is different than I thought it would be as well. I know that I claimed that I saw every beat coming. I saw every beat coming...except for one. Then I saw the movie for the fact that it was two movies. The central concept is that these two girls look alike in every way with the exception of a haircut. Okay, I can buy that so far. I'm actually pretty on board that idea. It's The Prince and the Pauper, only with two rich kids who happen to be related. The reason why Hailey Mills has to film every scene twice (with the exception of the hilarious stating of a double in many scenes) is because it is important that the two girls look exactly alike. But then, about 60% through the movie, the conceit is lost? The girls reveal that they've been setting up a parent trap? And we're supposed to be cool with that? I wasn't ready for that. I swear. It completely took my by surprise when they just up and told the parents. Then, they just confess their plans and expect it to work. I mean, of course it worked, because this is a Disney film and Disney kids don't get to have divorced parents. But I have to stop being a stick in the mud sometimes. I'm literally smirking to myself in an empty room, but I really kinda enjoyed it. For all my virtue signaling and white knighting, there's something really fun about the movie as a whole. The opening animation establishes this absolutely fantastic tone for the movie as a whole. Sure, the movie is really two movies (pre-and-post reveal), but those two movies are super cute. My parents never got divorced, so it didn't rip me in half thinking about this film. That's the most privileged thing I've written today, but it's true. It is a good movie...if the movie doesn't stab you in the heart and gets too personal. That's part of the whole thing. If you watch it as a cute movie, it's a super cute movie. If you are like me, remove your brain from the equation. Because the message of the film is troubling, the format of the movie is bizarre, and the logic is at best dubious. But who really cares? The movie is super cute and has some good gags. I also really like the song "Let's Get Together." If you watch it like that, it'll be a good time. And sometimes that's what you need on a quarantined Disney+ watch. Rated R for nudity, sexuality, violence, blood, and a lot of language. Sideways is a more R-rated movie than most of us probably remember. I mean, I never even addressed that there's just a ton of drinking going on throughout. That's all everyone really remembers. But no, it's straight up and R-rated film. I was running on the treadmill, terrified by kids were going to come down and something really vulgar was going to happen. It's pretty intensely R. We just forget. R.

DIRECTOR: Alexander Payne It's the wine movie! In 2004, that's all we got out of it. Remember when everyone said that they weren't going to drink Merlot? None of us really knew what that meant. I still don't know what that means. I'm not a wine snob, despite taking a class on my honeymoon. I told a joke at the table that cracked up the rest of the guests and the instructor hated me from that moment on. But I don't think people really watched Sideways the way it was supposed to be watched. Sideways is kind of the Fight Club of independent drama. That's a really weird statement and I really need to back that up in the course of this essay. Fight Club is a pretty great film that is completely remembered for the wrong reasons. Fincher, and by proxy Pahalniuk, is pretty damning of Tyler Durden's entire way of life. The movie makes this entire world look super sexy only to bring it down on its face. However, the big takeaway from the movie, by audiences, was to start fight clubs. The counter-culture stuff looked so attractive that, when the story shined a light on the absurdity of it all, the audience was still enamored by the setting of the film and lost the point of the film. The same probably holds true for toxic Rick and Morty fans. Sideways is a really deep film that happens to be outshined by the sexy attractiveness of wine country. There's a deep story there that challenges us. But Payne didn't want to be completely moralizing. He took the story of the manchild and entrenched it in the world of the wine connoisseur. It's kind of smart, by the way, the use of wine? This is a story about the growing up, or not actually growing up. People think that they grow up, but men tend to be the man-children that they have always been. Listen, I acknowledge that I probably haven't grown up that much. I wrote movie reviews of things I watched when I was in high school. I just organize them better and swear less. I have a basement full of comics and I am trying to figure out how to schedule video game time in an environment full of kids and a wife. The same needs that I had in my youth still plague me now. Miles's obsession with wine is an extension of the obsession that comes with youth and hobbidom. It's so weird when people walk into my classroom and wonder why there's a giant blue box labeled "Police Public Call Box." I have a handful of students who think I'm really into law enforcement. Our obsessions are both self-gratifying, but are means of finding kindred spirits; those people who are obsessed about the same things we are. It's not what you're like; it's what you like. However, we associate a knowledge of fine wine as something fundamentally adult. It's not drinking to get drunk. It's drinking in appreciation of labor. But that's Miles's big mistake. Miles, for all of his knowledge about wine and his years of obsession, drinks to get drunk...a lot. His entire life is a lie and he never really realizes that. He has created this persona that seems so mature and figured out, but really, he's as much of a mess as Jack is. Jack is there as a foil. Jack is the guy who has no wall. He is what he is. He is a bad guy. Everyone knows he's a bad guy. Miles is allowed to judge him all day. But the only thing that makes Miles look mildly heroic is the understanding that Jack is there doing something way worse than he is. And the thing is, Miles doesn't really grow. Okay, he grows slightly. But he keeps Jack's lie. I don't deny that it is an awkward position for Miles, narcing on your best bud on the day of his wedding. But Miles sees evil and wrongdoing wherever he goes. He's quick to judge and ride the high horse all day. But he's in a unique position to do something about it. Part of this could be read into the theme of childishness. Jack is a grown man able to make his own decisions and Miles's decision not to rat him out might be read as a respect for that boundary. But on the other end, because Miles as a character is the portrait of a man who is lying to himself, I read his choice to continue not narcing on Miles as a comment on the idea that he just wants people to keep liking him. Miles, as a character, isn't rewriting his code through this adventure. His code has a very specific morality and none of that is really challenging. Instead, and this can be seen as a positive thing, is the idea that Miles has to learn to start loving himself. I agree that it is bad that Miles doesn't really learn the lesson about being liked and growing up from the events of the story. But I will say that admitting that he can't do this alone is a big deal. Payne's good at finding the real shift that people make in life. Miles is a sad sack at the beginning and he starts understanding that he at least has to try to be a better person to find happiness. Payne offers that hope that Miles will someday becomes self-actualized and a better human being. That's what gives him an opportunity with Maya. Maya isn't perfect. She kind of sucks in her own way. But Maya is at least trying. Their relationship, while flawed, at least comes at mistakes from a point of redemption. By acknowledging that Miles chose Jack over Maya, there's the understanding that the two will screw up, but it isn't the end. It's not overwhelmingly hopeful, but it is a realistic understanding of hope. This was hard to write. I've been sitting on this movie for a week-and-a-half and I thought I had all this great insight. But sometimes it is difficult to write. The best takeaway I can give is that it is a movie that has been fundamentally ignored for its depth because people be lovin' wine. Payne knows how to shoot a pretty movie and he knows how to shoot an ugly movie. But the movie is more about what is going on than what is only aesthetically pleasing. PG-13, for dubious morality, language, and violence. It's what you would consider in a typical PG-13 movie, but teaching someone with a disability that amorality is cool can get a little dicey. It's both touching and kinda gross at the same time. The movie never goes full into "laughing at" as opposed to "laughing with", but if the actions done to Zak were done to someone without disabilities, the scene would play very differently. On top of that, there's a lot of loosey goosey attitudes about what is best for people. While heartwarming, if this happened to someone you knew, it would be tragic.

DIRECTORS: Tyler Nilson and Michael Schwartz There's no winning by writing this. I don't become a better human being. I don't become a better writer. What few readers I have left will probably disappear on me. Also, there's a chance that the person who recommended this movie to me will see it and feel betrayed by my disappointment in this film. For the few people who disliked this movie, I probably can't even be considered that intense about the movie either. It's a movie that I simply think is overhyped because it's been done so many times before. The credit it deserves is that it is a movie that actually offers proper representation. In the same way that Ben Kingsley wowed audiences by portraying a different race in Gandhi, it used to be cool to have an actor show off his chops by playing someone who lives with a disability. But like today, it's probably absolutely offensive to those actors who aren't being hired because they aren't handsome white males. Peanut Butter Falcon really hits on the same beats as Rain Man. If anything Rain Man offers something of more weight because it talks about the importance of family. But both Rain Man and Peanut Butter Falcon are trying to tap the same vein of sentimentality over substance. Zak's quest for independence is one that is valuable. But because everyone is completely enabling him, there's really no sense for long term growth. Zak is alone without a real sounding board. He's not really making wise decisions because he has no one to tell him the difference between a good choice. He has all these people who FEEL love for Zak, but ultimately aren't willing to make hard choices with him. His roommate, while good intentioned, doesn't have the familial responsibility to say that running away might be the worst thing for him. Because that's something that the movie is violently ignoring: Zak might die by leaving the nursing home. Eleanor is the antagonist who is, for a period, the only responsible character in the film. Trust me, I get really angry at Eleanor by the end of the film. I'm not letting her off the hook. But at the beginning of the film, she's searching for Zak not because she wants to capture him, but because she's honestly concerned for his well being. After all, both Zak and Tyler almost get destroyed by a boat. (I'm not quite sure how they aren't destroyed by that boat, but I'm going to lay that aside to the fact that my eyes were rolling back into my head for a significant chunk of this film.) That scene, while meant to ratchet up tension in the film and create some sense of danger, is actually really telling that this entire narrative is extremely dangerous. Eleanor is aware of the problems out there, but we're supposed to be rooting for Zak and Tyler's journey to the wrestling school. Tyler is a terrible character to graft onto. Absolutely the worst. For a storytelling perspective, Tyler is meant to grow with Zak. Because he's at this rock bottom place in his life, it gives him lots of room to grow. It's exactly what happens in the film. This dynamic is fairly standard in most storytelling. I would like Lady and the Tramp, although that changes the dynamic. Instead, I'm going to go Isle of Dogs. The gruff leader who needs to examine himself is a tempting protagonist. But Tyler's specific brand of rebellion is extraordinarily dangerous. The events of the story that have him on the run from the fishermen (that's right, isn't it?) is escalated by his destruction of the traps. When Zak attaches himself to Tyler, Tyler should be pointing out that the union would likely get Zak killed. There's this really casual attitude towards potential death over something that is pretty silly throughout. Which brings me back to Eleanor. Eleanor sets out in this movie to save Zak from a world that is way more harsh than most. Zak has never been out on his own, has very specific needs, and is bonded with a guy who is on the run from people who want to kill him. When she catches up to Zak and Tyler, her worst fears are actually realized. This is the worst case scenario. But she somehow finds the entire situation charming. She distances herself from her character's needs and becomes a member of the audience. Yes, I too want Zak to become a wrestling champion. The film told me that is what is desirable and I can get behind that premise. But that goal is absurd. The film has to have an absurd ending for that quest because there's a real problem with that being a final result. Zak, as the Peanut Butter Falcon, needs years of training. He'd have to come to terms with the fact that he'd be treated as a sideshow act. On top of that, there's a right way to go and a wrong way to go. On the run is probably not the way to do that. However, Eleanor has the resources to actually do this properly. Eleanor's not a perfect character at the beginning. She's close, but she's not perfect. I talked about how that antagonist is the one who actually has things right. Her problem is that she's overwhelmed by a crummy situation, so she can't see Zak's emotional needs as clearly as she needs to. What she learns in her hunt for Zak is the emotional necessity to make something out of his life. Great, that's a really good message. But with that knowledge doesn't mean that Zak can do whatever he wants in the way that he wants. Rather, her role is to take her advantages and contacts to figure out a plan instead of barreling forth to an ending that should have no chance of success. Please Stand By dealt with a very similar plot. But the protagonist's goal in Please Stand By was something reasonable and do-able. It was a series of responsible life choices that were being undermined. Eleanor's takeaway shouldn't be that Zak can do anything he wants if he believes. It should be that we can set reasonable goals that can be worked through together. I mean, the issue that everyone has in their head is that we are all aware that showing up at a wrestling school from an old VHS tape without doing any Googling is a road trip to disappointment. It's an absolute moment of disbelief that the Salt Water Redneck was willing to play along. In the course of the film, I realize that the biggest problem with this movie is taking shortcuts towards everything. The easy answer is to just continue with the journey and for characters to forget their motivations. Similarly, plot points just happen. There's no logic. The bad guys somehow become expert trackers. They just show up to the house they are staying without rhyme or reason. Remember, the bad guys are...fishermen. Similarly, Eleanor just...finds them. She's one lady who has no idea what path they are using to get there. She keeps stumbling onto their trail, despite the fact that the odds are completely against her. It's stuff like this that competes against the emotional resonance of the film. Emotionally and tonally, perfect. You did it. You fed a kid with Down Syndrome booze and we all got mushy. But it seems like low-hanging fruit. The conceit sells it all, not the storytelling. So the movie gives all the feels, but I wish it just took it to the next level. Rated R for language, sex, and violence. The language is a bit much in this one. In college, the first playwriting course that I ever took gave us free range to do whatever we wanted. The first thing I did was litter the script with the f-bomb anytime I got the chance. I thought that was being realistic. The script, at least tonally, looked a lot like Uncut Gems. There's so much swearing that it almost comes across amateur at times. I don't know if it grants it a sense of reality or just of language in itself. The violence isn't often, but it is pretty brutal. The sex kind of just paints the world. Regardless, this is a pretty well deserved R rating.