|

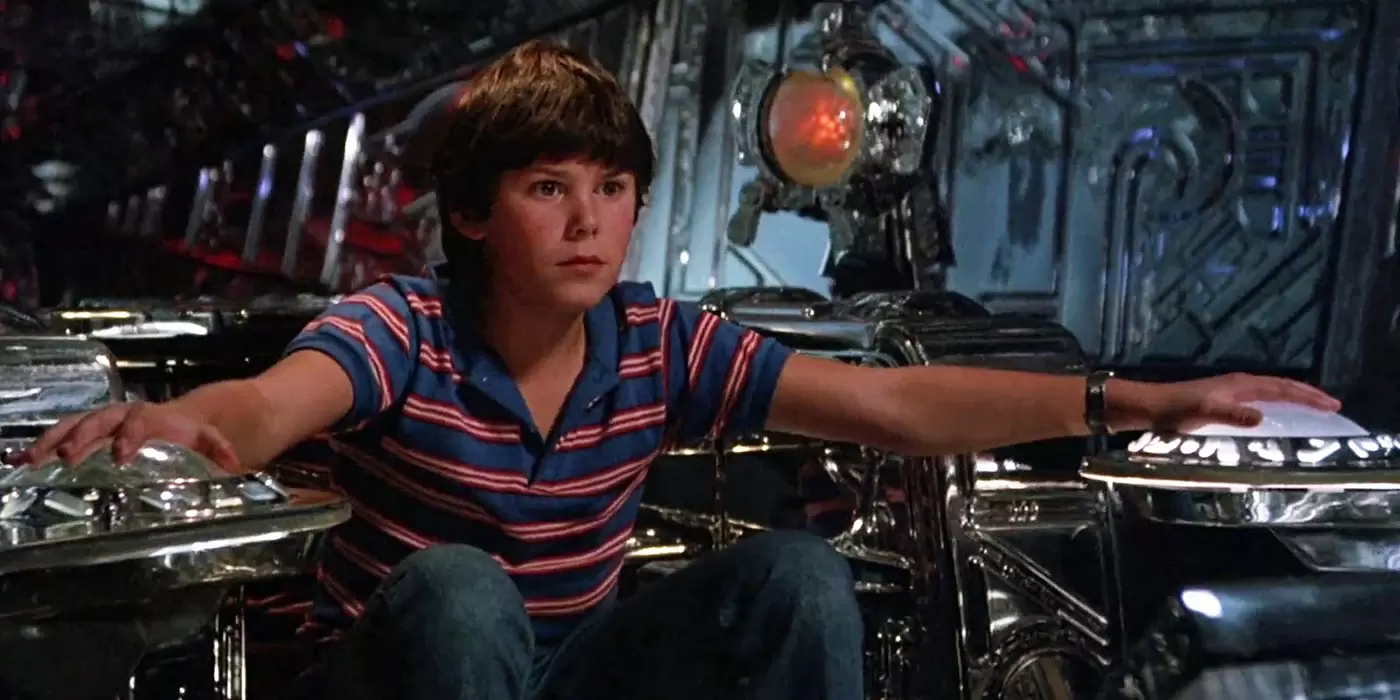

PG. Why is Flight of the Navigator so terrifying? It really is. If many many Disney movies put kids in peril, why does Flight of the Navigator stand out? Part of my argument later is that the peril comes from a very dangerous place. There's a lot of victimhood being touted around here masked by adventure. This might be one of the darker, if not sillier at times, Disney films. There might be some mild language as well. PG.

DIRECTOR: Randal Kleiser I'm in a pickle again! This is another one of those movies that fell through the cracks. I didn't write it in my To-Do List and then I passed it up. I'm only a month behind on this one though. I can write about something I wrote about a month ago, right? Also, I got booted from my Catholic Movie Geeks page. The struggle of being a writer gets no harder than knowing that even fewer people will have access to writing. I got booted for writing this very blog, so that's always fun. It wasn't for content. It just for self-promotion. You know, letting people read your blog? I'm pretty salty. When I brought up to my wife that my family movie night choices was going to be Flight of the Navigator, she thought I was nuts. I also presented The Goonies as an option, but I knew that wouldn't get through. The 1980s were a very different time for family films. The tone was just all over the place and the content was pretty intense. When she got anxious, I knew why. It's very hard to define why Flight of the Navigator is the next tier of family film. It isn't an innocent movie. I'm going to be using myself as an example, so please treat this only as anecdotal evidence, but I really believe that our heads and our hearts don't exactly communicate with us on this film. Having to summarize this film, I would wager that most people say that a kid finds his way onto a spaceship with the personality of Pee Wee Herman and escapes the government chasing him. It's not a perfect summary, but it will do in a pinch. I couldn't really fight that argument too hard. It seems like there's a family film in there. But there's something emotionally sinister about Flight of the Navigator that other films don't exactly carry. I imagine that Return to Oz would be the next step beyond Flight of the Navigator. Navigator never gets as sinister as Return to Oz did, although it has been a while. (I have no desire to revisit that right now. I don't need my kids waking up in the middle of the night screaming.) But the reason, in my head, why Navigator is so troubling is the argument that I started introducing in my MPAA section. Navigator surrounds the concept of victimhood. It doesn't really address it very well. It's not like David is all about taking back the power stripped from him as a child. There is an element of that, and I don't want to dismiss that. But David is very much a passenger on his own journey. It's ironic that the movie is called Flight of the Navigator because he has as much authority and understanding of his own fate as a ride at Disney World. Also, how is there not a Flight of the Navigator ride at Disney World? From David's perspective, he's completely devoid of responsibility of the things that happen to him. He treats his little brother with contempt. But regardless of the feelings that he harbors for his little brother, he would still have to go out to the woods to look for him. His brother is the one who enjoys playing pranks. It isn't due to David's actions that he is led to the hole where he falls. He falls in a hole and wakes up in the future. What goes from a sense of security goes into a darker version of what would actually happen to David? Instead of walking back into his life, he immediately gets involved in authorities. There's something that kids probably don't think about when it comes to kidnapping. I know that I tell my kids not to talk to strangers because they could get kidnapped, but Flight of the Navigator adds a sci-fi twist to that entire scenario to make it all the more real. Returning to one's own house to find it occupied by someone else is absolutely a haunting reality of a kidnapping victim that probably people don't think about. Because I have to state this very very clearly: Max is the bad guy of the piece. We're all emotionally attached to NASA being the bad guy of Flight of the Navigator. It's probably one of the few times that NASA comes across as being evil. It's actually weird writing that. Part of it comes from the idea that the government is the bad guy. If you want to take that stance, please do. Just realize that everyone's wearing a NASA hat and it technically is a government agency. But Max straight up kidnaps David. Sure, he talks like Pee-Wee Herman (eventually) and is super charming. But David had no sense of agency or permission in the story that allowed these events to happen. It's a nightmare for him when he wakes up. He is alone in the woods, old people live in his house. When he reunites with his family, they want to love him but can't. I take it back. The house thing is scary, but the idea that your parents want to love you but can't? That's where it kind of crosses a line. Because you are the exact same, they can't look at you. I can't help but think of Room (not The Room!) and how this might be a commentary on the other side of that. The victimhood becomes about time. It's about this fantasy that can never exist: the return to innocence. Which is what makes the end of this movie such a fantasy. If Flight of the Navigator is an allegory for missing persons reports and innocence lost, David is able to reclaim that time lost that no one else really has the ability to do. The movie, for all of its sci-fi tropes, really leans hard into the fantastic wishes of this kid. The movie straight up lies to us. It heavily implies that David wouldn't be able to survive the trip back in time. Max's choices throughout the story were to subject David to a series of disappointments and government experiments (which I never really got to tack onto the list of crimes that Max was responsible for). These things happened in an alternate reality. It all becomes part of a made up past for David that only he can't appreciate and understand. Yet, every single adult or advanced intellect in the story is ultimately selfish. Max uses David for his own understanding of humanity. The government uses David for an understanding of life beyond the stars. I don't know what Sarah Jessica Parker was doing, but she had a cool robot and that's probably pretty selfish, right? Honestly, this movie might be family-friendly torture [insert word here]. David has an escapist adventure, but only because he's dealt this insane pile of horrible events that he has no control over. There's no moral that David can really overcome. If he had turned left instead of right, he could have been saved? Nope. David is the definition of a victim and that's really played throughout the film from moment one. It's probably what makes the movie so scary. Most kids' movies stress a lesson to be learned that gets the protagonist into trouble. It becomes part of the internal conflict. "Don't do this", the moral screams, "or you'll run into trouble." None of that. I don't deny that NASA is actually objectively spooky in this movie, but that's one small part of a much larger fear mood. But that being said, my kids loved it. I loved it. I talk like this is some dire problem. It's just probably why Flight of the Navigator reads as something other when there are a bunch of other movies that put kids in danger. It's a fun film. I love the multiple levels of retro storytelling going on here. 1986 commenting on how advanced it is compared to 1979 is adorable. Regardless, just keep in mind why you probably feel a little nervous around this movie. It's the story of victimhood.

0 Comments

HA HA HA HA HA! It's so R-rated! SO R-RATED. Look at that still. That's a mild still of the things that you see in this movie. The movie is just littered with nudity. There's so much blood and dismemberment. It's the kind of blood that just squirts EVERYWHERE. If you want to laugh, there's child endangerment in here. The movie, and this is where I get serious, also is framed around rape. It's so R-rated everyone. Not for the feint of heart.

DIRECTOR: Buichi Saito One day, probably during some degree of quarantine, I'll finish all of the Lone Wolf and Cub movies. It's so bizarre that I want to talk about Lone Wolf and Cub nowadays. I loved The Mandalorian so much, but no one I know is really talking about how it is just a sci-fantasy version of Lone Wolf and Cub. It's been a while since I've watched any of these movies, mainly because they're a lot. I get the appeal of Shogun Assassin as a condensed version of these films because if I binged these movies, I think I would instantly get desensitized to a lot of stuff. I'm in the latter half of the film series...barely. It took a while to get through the first three. Something in me is inspired to just barrel through the final two. I enjoy these movies, but I don't think I've seen a movie in a franchise that represents "Part 4" of a serialized story than this movie. It's no that long of a film. It's an hour and twenty-one minutes long. That's a little baby movie. As such, it almost reads as an episode of television more than anything else in its structure. The movie introduces a really cool conceit. There's a woman. Of course, because these movies are as misogynist and bro-ey as you can get, she has to be topless for a majority of the film. Similarly, she has to be the victim of sexual abuse because this entire genre has some backwards morality. But this woman has to be the match for Ogami Itto. She's insanely fast with a sword. She's one of those villains that is both sexist and not sexist at the same time. She is the object of sexual desire for the movie, which isn't exactly progressive. But on the other end, she's a character worthy of respect both in skill and objective. We know that these two characters will spar because when you have an unstoppable force, what's the point without it meeting an immovable object? But then the story takes a really weird angle in terms of formula. There's only so much keeping these characters apart. There doesn't seem to be a direct tie between these two characters, so to put them on a path where they have to encounter each other means that the two must fight in that moment. Sure, the film has the option to break up the fight when Itto is losing, but I don't know if the filmmakers and storytellers are cool with Itto falling to a woman that we've never met before this film. Instead, Itto and Daigoro must fill the time dealing with minor scrapes as a means to remind us that these are characters with unimaginable fighting talent who must go around with the blood of others on their clothes throughout. As part of this stall tactic, the film gets a little bit confusing at the beginning. Itto's departure from Daigoro at the beginning is communicated to be something foreign and strange. While Itto regularly goes to the temple on this Road to Hell, Daigoro stresses that something is very different about this whole scenario. I'm a little confused that maybe I didn't pick up on something that I really should have because a lot of film real estate is devoted to what Daigoro is going to do in the absence of his father. We have this character who follows Daigoro around. The problem with spreading these movies around in the way that I have is that I feel like I should know who that character was, but I straight up don't. I got the vibe with the use of flashbacks that he's been in the other movies. But he's right there in Itto's origin story. I'm not sure if this is a retcon or a flashback, but the movie keeps pulling me away from what I should consider the main plot: the tattooed woman. Daigoro spends his time in this movie looking like a little psychopath. I don't blame the movie for focusing on Daigoro. The narrative is an absolute mess of episodic adventures, so we need to have something compelling to make the fourth entry in the series something that has meat and value. Daigoro is the conceit of the film. It's what makes the Lone Wolf and Cub movies, besides the over-the-top sex and violence, different from other samurai films. Most brutal assassins don't bring their children into battle, but that's what makes Itto so interesting. Yet, there's few moments where Daigoro a liability. He's almost part of the cart. But like The Mandalorian, he's possibly the most fascinating character. With it's ugly structure, the silver lining is that Daigoro has some time to be in isolation. We know that he's a stone cold killer as well. He just lacks the hand-eye coordination of Itto, so he's can't do crazy sword work. Daigoro in isolation though, not juxtaposed to Itto, provides a look into his psychosis. Watching him walk through the field on fire is a great visual image. I get the vibe that there wasn't too much concern for the kid's safety on set. That's a lot of me guessing versus having evidence, but it also makes crazy sense to me. There's this narrative going on by his little stalker guy which both builds Daigoro's character and the stalker's character as well. It's a really interesting opportunity considering that so much of the movie doesn't work. I don't love throwing the word "Mary Sue" around. It's horribly sexist, but Itto completely obliterates the line for Mary Sue in this movie. A Mary Sue can't be stopped. He or she is able to accomplish anything that they need to do and there's no threat of death. There's a reason that there's a term for this archetype. Batman has a lot of that going on. I actively disliked the original Charlie's Angels movies for this reason. But what happens when a character is a Mary Sue is that death has no meaning. The film ends with Itto and Daigoro against an entire army. They are pinned down in a quarry, probably for budgetary reasons, and there is no hope of escape. Itto takes on tons of guys. He actually does a pretty good job. He takes reasonable damage. But the movie really turns into the level of a video game when Itto takes down every single minion and then has a boss fight at the end. That boss wrecks him. Absolutely wrecks him. There are a handful of moments where the choice becomes binary for the screenwriter. It's either that Itto dies in this moment, which probably wouldn't be allowed, or someone else has to save him. There are just too many puncture wounds in one character to justify that Itto saves himself. But the lazy writer adds a phrase something along the lines of "And then Itto rallies once again" and wins. The movie ends with Itto trailing buckets of blood that he's losing before the credits roll. I want to say that this is a cool moment. As a visual choice, it actually works really well. It's a cool concept that Itto can get wrecked. It starts that there might actually be stakes to the whole thing. If Itto can be killed, there's actually a risk to the storytelling. The problem is that Itto takes way too much damage. Even if Itto didn't die from those wounds due to plausible deniability, he shouldn't be able to go on. I almost wouldn't mind if the story started with Itto healing from his wounds somewhere else. But Itto staggers. If the franchise ended with Baby Cart in Peril, then you would imply that Itto would have died minutes after the movie ended. But we know that he comes back for another entry. As much as the film wanted to give Itto some degree of vulnerability, it actually does quite the opposite. Itto can take any kind of damage and clearly none of it is. The only way that he's actually allowed to die is if the entire franchise ends. It's always presumed that Itto wouldn't die before the last film, but giving him conditions where he should die really highlights the flaws of watching movie where there are no consequences. The evil part of me likes this movie because it is just fun action. The world of Lone Wolf and Cub kind of borders on a fantasy realm. There are moments where the supernatural come into play, or at least things that toe that line. It's absolutely shameless and it really plays on the worst instincts of filmmaking. Completely lacking subtlety is normally a turn off. But I can't help that I admit that I enjoy these films. Part of it definitely comes from the fact that I never tried binging these movies. There's one thing that the series hasn't been and that's boring. But that also being said, it's not much actual substance. It's putting away a whole birthday cake in one sitting. You can do it, but it makes you feel kind of gross that you enjoyed it that much. You also shouldn't do that very often. Also, you'd have to cover the birthday cake with a lot of sex and blood and that's not something that's probably healthy for anyone. Yah! A G movie that is genuinely pretty G rated that's not criminally aimed at babies. Okay, it's a little scary. If they branded it with a PG, there are moments that are a little spooky. Like, there's some scary jaguars and bats. Kuzco is more than a little bit of a punk. There's some very questionable behavior on the part of the protagonist, but that's simply because it is his internal conflict. It's G and I'm standing by that.

DIRECTOR: Mark Dindal I'm flabbergasted that I haven't written about this before. I searched for it and I was sure that I had written about it. You see, a few years ago I tried showing this gem to my kids and they did not care for it. Kids are finnicky like that. This time worked out far better. They have at least some degrees of senses of humor (there's gotta be a better way to say that) and they were able to appreciate the fact that this was just a funny movie. For some reason, The Emperor's New Groove might be one of Disney's cult movies. I understand a lot of the movies in the Disney archives acting as niche pictures. I'd probably throw a lot of the live action movies in that category. Maybe I'll also throw The Great Mouse Detective and The Rescuers as well. My only theory is that both The Great Mouse Detective and The Emperor's New Groove are animated features that aren't actually musicals. I'm sure that there's some Disney suit who hears that an animated picture that isn't a musical comes through the pipeline and instantly freezes up. But then again, the Pixar movies do just fine and they aren't musicals. Sure, we have the lovely pipes of Randy Newman on the Toy Story movies, but these aren't diagetic moments in film. Rather there's no music. However, The Emperor's New Groove might be the most rewatchable film in the Disney archives. A lot of that is subjective. This came out in 2000. I talk a lot about the weird cinematic age that lasted from 1999 to 2002. It was just a weird time to make movies. But The Emperor's New Groove decided to take a different tone than its contemporaries. Perhaps taking influence by the shock culture of Howard Stern and the era of political incorrectness, The Emperor's New Groove feels like a small movie that just really wanted to be its own thing. Its protagonist, Kuzco, is fundamentally unlikable. We've had protagonists before who have unlikable traits, but are mostly heroic. I guess it's not completely its own thing because A Christmas Carol also does this with its protagonist. But The Emperor's New Groove only really winks at its source material compared to the fairly reverent animated version of "A Christmas Carol." But despite having a protagonist that is a huge jerk, the story works really well. Part of that comes from the idea that internal conflicts are always interesting to me. Kuzco is painted in large swaths. It's not exactly nuance with what is happening in The Emperor's New Groove. He's a jerk. He makes a friend. He's no longer a jerk. But the way that this film is created is what allows for this unlikable character who has fairly simple motivation to stand outside of other characters of his ilk. For those not in the know, Emperor's New Groove plays heavily with metanarrative and breaking the fourth wall. Kuzco acts as a narrator to the events. But similar to a character like Deadpool, he is aware that he is in an animated story for kids. He has very specific knowledge that he should not have. He actually has control over the film. The consequence of this is that Kuzco is able to split himself into separate personalities based on where the narrative falls. As a means to deceive, Kuzco starts the film, as a narrator, commenting on a later element of the story from the point of derision. This creates multiple unreliable narrators. From our initial perspective, we get the Kuzko as introduced in the beginning of the film. He is a braggart who sees himself as the victim of misfortune. Everything is everyone else's fault. But this is oddly telling because he actually despises the character who has some degree of emotional growth. That llama weeping in a storm should cancel out the narrator Kuzco. The narrator, again, is aware that he is in a movie and retelling the events of the story to an audience. This presupposes that the narrator would be telling the story once the events are complete. Wherever the initial Kuzco comes from is an odd anomaly, but one that our brains are completely willing to accept. But we can't forget that this is a Disney film. Complicated narrators and problematic protagonists aside, the story has a fairly straight forward moral. Playing up the idea of trust and self-sacrifice, Pacha acts as a foil for the selfish Kuzco. It's really weird, because we get that Pacha is completely the model for heroism. He is a loving father. He takes a lot of abuse. He has everything to lose in the story, going as far as being imprisoned for life. But he doesn't always come across as perfectly heroic. There are times where Pacha suffers the same character flaws that Kuzco does. He realizes, as part of the journey, that he must convince Kuzco that his home is not to be demolished in repayment for his friendship. This is Pacha's internal struggle. The moral, upstanding father that Pacha is, he is aware that there is always a risk that all of this will come crashing down on his head. But the movie addresses Pacha's conditional altruism directly. Kuzco calls him out for this duplicitous charity and we actually are forced to look at the bastion of goodness in a different light. I like that Pacha is overall a good guy, but kind of sucks. It's hard to relate to Kuzco. He's a commentary for the rich. The rich probably won't change their behavior based on a viewing of The Emperor's New Groove. However, Pacha acts as far more of an avatar than a talking llama emperor. Pacha knows that he's a good guy, but is forced to reevaluate his decisions in light of confrontation. It seems like I'm doing a deep dive into something that seems pretty common: a character who is not perfect. But usually the character flaw is tied directly to the sense of inadequacy. Instead, Pacha is actually very much the yang to Kuzco's yin. Humanity / llamahood is selfish. It just takes the greater man / llama to place that need in check. Also, there's never been a better character than Kronk. I have no analysis that's worth its weight in salt for Kronk. I will say that Disney has a history of making fun sidekicks for villains. Okay, mostly I'm just thinking about Iago from Aladdin. But Kronk is straight up a good guy accidentally being a bad guy. I don't think I'm in the headspace to watch the direct to VHS sequel, Kronk's New Groove, but what did it take to get this good human being to be such a great villain. Sure, he's dumb (but that's not even accurate!). But there is this great archetypal commentary by having Yzma juxtaposed with Kronk. It makes Yzma so much better. I actually feel bad for Eartha Kitt because she's so good in this role, but completely overshadowed by Patrick Warburton. I want to say that they are a pair, but Kronk steals every single scene he's in. I love this movie. Most people love this movie. I actually don't know of anyone who isn't mildly obsessed with this movie. I'm going to hear from people I haven't heard from in years for posting this. Another PG James Bond movie with straight up nudity. Maurice Binder's title sequences always throw these movies' ratings out the window, especially in the advent of high def film. There is so much nudity during "All Time High" that very little is left to the imagination. It also has a wildly offensive title. A movie named Octopussy is rated PG. Oh, it's exactly what you think it means. A clown gets a knife to the back. All sorts of people are killed. India gets that sense of otherness to it. This might be a light R in reality. But guess what? That's not my job. PG.

DIRECTOR: John Glen Oh my. Do you understand how much I wish this movie actually followed Ian Fleming's title for this story? The original story, which the film is loosely based on, was entitled "The Property of a Lady". That title actually has a lot more in common with the content of the film than Octopussy. Really, it's absolutely bizarre that this movie is called Octopussy considering that it is just named after one of the characters. Goldfinger had the same issues. Thunderball was the name of the operation. But really, just naming a character something loaded with innuendo and then naming the film after it? That's a bold choice. I wonder if it had anything to do with Never Say Never Again. For those people not in the know, Octopussy came out in 1983, the year I was born. At the same time, another production company found a loophole in the rights for Thunderball, and decided to release their own bootleg James Bond movie the same year starring Sean Connery. I choose not to talk about that travesty. If I have the legs to keep writing about movies forever, I might get around to watching Never Say Never Again. But Octopussy does probably draw a lot more attention than a film entitled The Property of a Lady. (I absolutely adore that as the title of a Bond movie and I actively wish that Never Say Never Again was never made.) A lot of people don't care for Octopussy. I genuinely look forward to watching Octopussy every time. For a while, it was up there with my favorites. I'm sure that if I ranked all of the Bond movies, I might be able to say that it is still amongst my favorites. We're about to hit a little stretch of really fun Bond films. People comment on the Roger Moore era as the time of goofballery. I can't really fight them. If you put a list of the silliest Bond movie moments, the Roger Moore films probably have a lot of them. But I don't have a problem with goofiness for the most part. The problem that a lot of the Roger Moore era movies had was finding a sense of identity on its own. Live and Let Die, for what it was, started off strong. It identified that the world was changing and that Roger Moore was not Sean Connery. It let Roger Moore be Bond in the way that he saw most fit. But like what would define this entire era, Live and Let Die was a response to blaxspoitation. It wasn't quite its own thing, but the thing it was mimicking was pretty entertaining. The Man with the Golden Gun employed Herve Villechaize as his character of Tattoo for a darker version of Fantasy Island. There was a Bond plot woven into it, but it didn't really say anything all that original. Moonraker was unabashedly trying to be Star Wars and 2001: A Space Odyssey. For Your Eyes Only was an attempt to course-correct from this series of trendy knockoffs without really establishing what it wanted to do. Octopussy, however, is perhaps the most Moore film in the canon without the excuse of chasing or avoiding cultural trends. Moore is silly, but the movie exists solely for itself. It's an odd commentary on Broccoli and Saltzman that it took ten years to really figure out Moore's Bond. Part of it, I think, comes from the idea of the Cold War understanding what it is. Connery's Bond was always under the thumb of SPECTRE. SPECTRE was always an excuse to talk about the Russians without directly talking about the Russians. It's odd because I remember the actor who played General Gogol in SPECTRE early in the day. The conflict between the West and the U.S.S.R. was always so much more complicated than the Bond movies would allow. SPECTRE allowed for Bond to fight a secret evil. It's only once the Cold War ramped up in the '80s that the Bond movies were really allowed to address the Russians as they were: complex. Bond couldn't just go around invading Russia because the Cold War prevented such things. But the tail end of the Cold War would start showing Russian desperation. Some of the cracks of the unknown enemy came to light and that makes for excellent storytelling. Instead of the Russians trying to grasp at some nuclear secret, it became about a grab for lost power. When the Russians in Bond's world were strong, it became two unstoppable forces. However, Octopussy plays up the idea that there is a hint of reasonability behind the Russians and their decisions. Instead of being KGB driven madmen, it became an argument for and against moving into the modern era. The scene around the map room under the spectre (sorry) of Vladmir Lenin is extremely telling. There's that element of the past and the move towards communism, but most of the room understanding that the U.S.S.R. was part of a global community. That's why General Orlov makes such a good villain. He's an extremist. He sees the good old days of violence and military superiority and he sees this dove trying to take it away from him. Orlov makes Russia seem somewhat real. There were the "good old days" (no there wasn't, but that's a lesson in history that I don't have time for) and that's what we shoot for. It's a little scary that the same attitude that General Orlov has in Octopussy kind of parallels "Make America Great Again", but that's a whole 'nother can of worms that I'm not getting into. Bond was never really about the complexities of the political theater. It was always about England being the good guys and the Russians being the bad guys. Somehow, Octopussy gets to have its cake and eat it too because we still have the "us v. them" attitude that other Bond movies have, but the movie presents it in a light that's interesting...and on the global scale. Putting the beginning of the movie in Cuba, one of my favorite Bond opening sequences by-the-bye, cements the idea of the fear of communism worldwide. Yeah, it has a pretty conservative view of communism, but that fear was of the communism of 1983 and it makes a ton of sense. But I also get why people don't really dig Octopussy. While it falls at the higher end of my list of Bond movies, the story doesn't really make a lick of sense. At the end of the day, when everything falls apart in the story, it becomes about money. There's this image that is absolutely haunting at the beginning of the film that acts as a phenomenal inciting incident. The body of 009, dressed in full clown regalia, crashes through a window and drops a Faberge Egg. It's this great puzzle to solve. What is up with that egg? Why is it so important? Ultimately, the egg itself isn't important. It is representative of the soviet financial treasure chest. That's not so interesting. And I hate to say it, because I really like the story, but there is no direct connection between the egg and the nuclear weapon at the end. Part of it is that the bad guys are super sloppy with their intentions. They draw a lot of attention to themselves with the egg. The possession of the egg doesn't actually directly tie to the villains' main goal: the incitement of war with the west. Kamal Khan, who has a really dubious connection to all of the events in the story, fights tooth and nail to get the egg back from Bond. It even goes into a "The Most Dangerous Game" reference for a while. But really, Khan and Orlov could proceed with their mission to blow up the base with a nuclear weapon without the egg. It's just that people would have figured out their plan...which they did anyway. As a Macguffin, the Faberge Egg doesn't work the way it is supposed to. Ultimately, what makes Octopussy work is the individual elements thrown together. It's not good storytelling. I acknowledge that. One of the problems with The Spy Who Loved Me was that it felt like the world hopping that didn't give it a sense of cohesiveness. The same thing happens with Octopussy. The only difference is that these scenes kind of work for me. There are a bunch of set pieces that absolutely shine in Octopussy that make the movie worth watching to me: the jet sequence in Cuba, the cab in India, "the Most Dangerous Game", the train fight, the bomb defusal, the raid on Kamal's fortress. That's a lot of good time. When the story doesn't work, that kind of becomes okay because the movie really almost acts as an anthology of loosely related Bond adventures. The movie feels like a bunch of pre-credit adventures that have a common storyline. Somehow, there's a way to tie all of these stories together. As of right now, it is a bit fragmented. Can I tell you one thing that happens in Octopussy that I don't see in Bond for a lot of the other films? The one thing that On Her Majesty's Secret Service gets really right is that it makes us care about death. When Tracy dies, it is absolutely crushing. It makes sense. Bond loses someone he absolutely loves. But Bond loses all kinds of other people in his adventures. "He has a license to kill or be killed." But usually, supporting characters don't evoke any kind of emotions. Not with Vijay. Vijay is this great character who is being built into almost being the Indian James Bond. He's this wonderfully charismatic character who bounces a lot of fun ideas into a Bond movie. Yet, he dies. The movie, wisely, builds this character up as our avatar character and then eliminates him fairly brutally. We care for our own reason, but we also care because Bond cares. I like the idea that James Bond has emotional reactions to things. This later wouldn't work as well with Licence to Kill, but I'll get to that when I get to that movie. When Bond feels actual pain, it really sells the idea that Bond is not a Mary Sue, but a relatable character that is interesting. I admit that Octopussy is far from a perfect film. I'll even go as far as to say it's far from a perfect Bond movie. But as an experience of what the Roger Moore era should have been, Octopussy is such a fun time that I can't wait to watch it again. I was actually getting burned out by Bond, then this movie showed up. That's saying something. It's PG, but 1980s PG. That's a very different beast. Yeah, still completely tailored to kids. I think the '80s aimed movies at children my kids' age, but didn't really care about what was considered appropriate. My anecdotal evidence is that I turned out fine, but there were a handful of really cringey moments, like when a preteen screamed out that she was sexually assaulted by the antagonist in a crowded casino and the director probably put that in there for laughs? Also, just casual language. You were totally allowed to swear in kids' movies in the '80s. Regardless, PG.

DIRECTOR: Todd Holland I did it. You see this? I went back to my childhood to a movie I knew wouldn't hold up and decided to challenge its cult status. It's because I have nothing to lose. My blog is still in Facebook jail and isolation is bringing the worst out of us. So I'm just going to sit here, on a Friday, and write about The Wizard. People my age love being the one to remember The Wizard. It's on par with dropping a Denver the Last Dinosaur reference in conversation. Those people who were just emotionally moved by what I just wrote, you know exactly what I'm talking about. My generation gets blamed for being nostalgia hounds. We are, but other generations are as well. It's just really easy to jump back into our generation of nostalgia because it's so easy to get a hold of. As everyone points out about The Wizard, it's a Nintendo commercial as a movie. We all remember the poster child for the '80s, Fred Savage, going to a tournament and having to see a Power Glove coupled with Super Mario Bros. 3. (Odd true story: I got an advance copy of Super Mario Bros. 3 from the video store somehow. It didn't have a box and it was already tagged with a "Be Kind, Rewind" sticker on it, but I played that thing, like, two days before anyone else did. This sound spurious, but I'm fairly certain that happened.) Well, the Power Glove and the Mario 3 thing weren't in the same scene and it wasn't Fred Savage who was playing. Also, you probably completely forgot that the movie also starred Beau Bridges and Christian Slater. At least I forgot that stuff. The Wizard almost could exist as a movie. There's this thing where I see this director wanting to make the next Rain Man. I won't be dancing around the Rain Man comparison. He's got this story and he's got a pretty impressive cast. People are immediately reeling from the phenomenon that is Rain Man and imagine if it was with children? Geez, that's got to be a punch to the heart, right? There are so many moments where I see Holland trying to craft something marvelous. He's got this kid, walking down the highway, hauntingly chanting "California." (I, after seeing this movie as a kid, would walk around my house also chanting "California" because I haven't changed a bit.) There's this story of child endangerment and abuse. There's a story of friendship. He's got a bit of a budget. But, and it's not the first time I've griped about the studio system and corporate America, he's got these financial overlords just looming over him. If you ever watched the later seasons of Chuck, you'll know how bad sponsorship can get. I know that that the suits behind this movie wanted to capitalize on Nintendo. I know it. It was probably even pitched to Holland with that premise. But I'm sure that he thought he could rein it in. He couldn't. What ends up happening is that The Wizard ends up being a cautionary tale that Hollywood has only heeded on occasion. Sometimes, cross-promotion can be too much. I remember watching CastAway and I would just get actively annoyed how many FedEx things showed up in that movie. All the boxes looked amazing and they all were side up. The Cheerios box in Superman: The Movie keeps pivoting to hit the ray of sunlight through Ma Kent's window. But I don't think anything takes the cake like The Wizard. There actually might be something of meat behind the Nintendo swag. Yeah, going across the country to enter a video game tournament seems pretty pandering, even for the '80s. But at the heart of the movie is a desperate attempt to discuss the complexities of family. I'm sure that some of the suits would have killed to find a way to talk about how Nintendo brings families together. There's a little bit of that inside The Wizard. But ultimately, there's a story about these kids and how no one understands them. One of them is in criminal need of bonding and the world keeps using him as a pawn. At its core, there is something really moving about The Wizard. But every time the movie exposes some degree of vulnerability, Fred Savage has to say something about "getting 50,000 points in Double Dragon." This is silly of me to bring up, but does it feel like The Wizard was made by someone who genuinely does not understand video games. I know. It had to be a screenwriter. Nintendo probably gave him a list of games to mention: Double Dragon, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Rad Racer. But when these moments come on the screen, you really learn about as much from these games as watching a commercial for the game. No one was playing Double Dragon for the score. I know that cabinets thrive on the idea that, if your score was high enough, you got to put your name into it. But Jimmy was playing that cabinet for a few minutes. If it came down to score, those kids would have noticed just the hours that he had been playing that machine. The value that The Wizard holds to today's society is the idea that video games became mainstream. Very much like how Hackers was an inaccurate portrayal of "hacking culture", The Wizard oh-so-desperately tried to pan to an audience who wanted to have their seminal film break box office records. But what actually happened? I don't know if hardcore gamers worship at the feet of The Wizard, but I get the vibe that they don't. The movie drops these video game references in without an actual love for the product they are selling. When I watched Wreck-It Ralph, I knew that the people who made the movie were genuine video game fans. There's so many references, but a lot of them are stuff that was clearly precious to them. Yeah, Sonic shows up for a second. But really, the movie is full of notes to classic titles. These are things that the creators grew up with and wanted to share. It becomes something made out of love versus something made out of necessity. Now, I'm not the biggest NES Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle fan in the world. I really got the vibe that the references that Beau Bridges throws out are completely and utterly made up. Who knows? Maybe I'm wrong. What I do know about the NES Ninja Turtles is that there is no way that Beau Bridges would get hooked on Nintendo based on that very rage-quitty game. There's one thing that you can really take away from that game and that is the fact that it is almost unplayable. They even show in the film the infamous underwater level. You know that first time gamer Beau Bridges was playing that water level and saying, "You know what, I get it now." Nope, he'd be shattering that controller into a million pieces and probably growing more distant from Christian Slater as opposed to closer to him. I was going to ask this movie why it was so afraid to be vulnerable, but I think we all know the answer to that. As I have stated, the studio wanted something poppy and commercial. They had this sponsor with Nintendo, who wanted to move as many bits of product as possible, including this mythic new Power Glove (that worked nothing like it did in the game. Trust me. I know from experience) and they had these titles that needed advertisement, including the super rad Super Mario Bros. 3. There was a director who had a loose outline of a touching story and if it was finessed just a little bit, it could turn into something important. But I'm sure that the studio kept peeking in and pushing a little more in. Then Universal Studios showed up and then offered more money. Despite the fact that the central focus of this essay is The Wizard as a cautionary tale, it did exactly what it was supposed to. Do you understand that everyone my age remembers The Wizard to a certain extent? The movie wanted money, but it also didn't want us to forget the awesomeness that was Nintendo. Yeah, there's no one shooting for those legacy points, but The Wizard permeated culture way more than it had any right to. Even the most general analysis of this movie would deem it a Rain Man knock off. The more accurate interpretation is that it is an hour-and-a-half commercial for Nintendo. And yet...I watched it as an adult. I introduced my kids to it. And I'm weirdly okay that I did. PG, for crude humor. It really rests in that space where parents cringe a little bit, but kids go absolutely nuts. Really, you could pair Hop with stuff like Captain Underpants. There's a good deal of poop jokes. An odd situation where it plays up blindness as a conceit. E.B. himself is pretty rude throughout the movie. The bad guy gets pretty threatening. Nothing that would be considered overtly offensive, but it does kind of come down to taste for Hop.

DIRECTOR: Tim Hill Do you know how hard a shift it is to go from writing about 28 Days Later into pivoting to Hop? My wife even called it. The movie was over and she said something along the idea of "Ha! You have to write about Hop." At the time, I thought it was going to be my pleasure. I had a germ of an idea of how to approach it and I've written about far worse movies than Hop. But then, the sun decided not to come out today and the wife and I are having political differences. I'm a very sensitive little boy and I don't want to be writing right now. But when you see that I wrote way too much about a CG crass bunny / buddy comedy with James Marsden, you'll know that this is all an exercise in willpower and of maintaining a routine. I didn't hate Hop. I missed a few parts. One of the interesting consequences of doing a family movie night every night during quarantine is that the kids love having the routine, but also make it way harder to watch the movie closely. There are some moments that I'm a little lost on. I don't quite get the characterization of David Hasselhoff. It could be that, like his many other cameos in things, the entire joke is that David Hasselhoff is there. I also don't know if E.B. really makes the switch he needs to for the story to actually have a moral...you know, for kids? But I caught it close enough to get more than foundational elements of the movie. If I'm way off, call me one it. I'm not going to host a private screening after the kids go to bed to really confirm a lot of my discussion points, so keep that in mind. If I'm way off, you're probably right because I missed, mentally, 5-10 minutes while begging the kids to shut up and watch the movie. I think I've learned that James Marsden was born to interact with CG cartoon characters. For most of his career, I've thought of Marsden as Cyclops in the X-Men movies or as the guy who keeps dying in Westworld. But Marsden actually has a very specific talent that I didn't think that people necessarily wanted. It seems like movies that cast actors across from animated characters, especially computer generated animated characters, are making a throwaway movie. If you are using Hop as the only bit of evidence for this argument, you might have a point. There are some really unpolished elements of Hop that allow you to fight for any opinion about this movie. Again, I thought it was fine, but that's because I had really low investment for the movie. But Marsden crushed it across from Sonic in Sonic the Hedgehog. The thing about comedy is that it is something that works really well when you play off of someone. It's about that give or take. I don't mind what a lot of comedians have done with quarantine videos. But there's something a little off about even the best of the quarantine transitions. There still is some quality, but it doesn't feel the same. Marsden might be one of those people who has an understanding of what it means to act across from a tennis ball and still make it seem believable. I don't know if Russell Brand was on set or anything, but Marsden makes his interaction with E.B., the tennis ball morphed into a computer generated bunny, pretty believable. It's got to be a talent and a lot that translates to the film. So far, this is all evaluative versus analytical, but it also is probably my greatest takeaway. I really feel like Hop might have been James Marsden's audition tape for Sonic the Hedgehog because the movies are just so darned similar. Should I get into it? I guess. I mean, I fill this section with nonsense anyway, so let's be explicit. James Marsden confronts a CG animal with attitude. He's been displaced from his home and has to get to a location to restore the status quo. They initially don't get along, but thanks to the faith of James Marsden, the two become a dynamic duo, looking out for one another as the villain gets closer and closer to destroying the pair. It's the same movie. But that's not really where I want to go. That's more of a commentary that kids' movies tend to be really formulaic. The movie that I want to comment on was Noelle. Now there's a movie that really owes a lot to Hop. I know that other movies have talked about the concept of replacing a mythical successor. With Noelle, I talked a lot about The Santa Clause because everything is ultimately a knock off of something else. But Hop gets points in my head. Noelle had the idea that someone who wasn't built to be something got to be something. Hop might get a little icky because a white man earns more privilege through his actions in this movie. I want to talk about that forever now that I just thought of it, but I do love the fact that this is about Easter. Easter is fundamentally a religious holiday. Christmas always has the argument whether it is a holiday for everyone or fundamentally a religious holiday. That gets pretty complex. But treating Easter like it is Christmas brings up a some funny concepts. There is this seriousness to this comic film that is infused in a way that I haven't seen done with Easter before. Listen, I have no problem telling my kids that the Easter bunny is fake. Not many people are really fighting that battle because it is really silly. But I'm thinking of the final act of Hop. It takes a lot to like E.B. He's a character who, despite being the protagonist, keeps breaking the rules in ways that he knows he's doing so. With a character like Paddington, the protagonist breaks the rules by accident a lot. He causes all this trouble trying to do the right thing. E.B. keeps making selfish choices. I'm going to be writing about The Emperor's New Groove soon, which also connects to the many many examples of these kinds of characters, but The Emperor's New Groove doesn't mince words. I think the filmmakers want us to cheer for EB. So when he represents Easter, the thing we're fighting both for and against is that Easter will be ruined by a character we don't really bond with. That's where James Marsden comes in. He's kind of a waste of space too, but his crimes are far more passive than E.B.'s. He's the character we can actually bond with. With these stories, where there's a CG character bonded to a protagonist, I always assume that the protagonist is going to be the cartoon. But I might be wrong. In those cases, the characters stay pretty static. It's the human who becomes far more dynamic. But this leads me to the role of privilege. I don't think I've ever seen a movie that promoted first world white people problems harder than this movie. This is an adult who lives at home with his parents who rejects every job that comes his way because he's too good for them. He lives very comfortably. Even when he housesits, it is for the most unbelievably expensive house I've ever seen. The character considers himself special, made for greatness. But there's nothing really all that special about him. I get that he's made for something better. It's almost built into the American Dream, the idea that we can become anything that we want to be. But there's probably a mistake there that could have been avoided. Lots of stories, from Death of a Salesman to Office Space dance around the idea of wasted greatness. When Fred rejects jobs, it's kind a of a problem that a bunch of people can't relate to. But look at Office Space. The protagonist works and is miserable. Yeah, he's kind of a jerk. But, ultimately, he's not doing anything wrong. It's a noble quest to fight for greatness. Lots of stories play with that concept. But being lazy and demanding to be taken care of makes the character kind of unlikable. With Sonic the Hedgehog at least, James Marsden plays a cop who wants more. That's proactive. The 2011 slacker is really a terrible character to be reinforcing for the greater good. His father should actually be mad. And now I realize that the father is Gary Cole...who was Lumbergh in Office Space. Hop's biggest problem is that it is TOO generic. It doesn't have anything all that special about it. That's not the worst thing in the world. It was an entertaining watch. But in terms of being a holiday great, there's not much to really sell here. Rated R, mostly for brutal murder and rape. There's drug abuse with a child and I forgot mostly how much nudity was in this movie. Danny Boyle is really good at making things so visceral that it becomes really, really uncomfortable. The volume levels in this movie are alarming. A good chunk of the movie is painfully quiet only to startle its audience with blaring screams and guitar riffs. It's a very R-rated R movie.

DIRECTOR: Danny Boyle It was never really my intention to watch 28 Days Later during a worldwide quarantine. There's actually been too much crossover with the misery outside in terms of my media selection. But it was literally the next movie in my Fox Searchlight box set and I always remembered liking this movie, so I decided to give it another go. The long and short is that the movie is still a great time. in some ways, it's better than I remember. In some ways, it's worse. I'm going to cover the "worse" thing first. Shaun of the Dead references the stupidity of this movie quite a bit. I always thought it was the one bummer part of Shaun of the Dead because I consider that to be one of my favorite movies. But maybe Edgar Wright and his team were right. The comment they made about 28 Days Later might be accurate. It seems really nitpicky, but it actually holds a little weight. I'm referring to, of course, the Rage-Infected monkeys. The opening of this movie is actually pretty dumb. I partially give it a pass because the rest of the movie holds up. But Danny Boyle is desperately trying to say something here that doesn't really have a lot of weight. The opening of the film shows these monkeys forced to watch cruelty. Mirroring the conditioning that Alex receives in A Clockwork Orange, these monkeys are the product of our hubris. They are a commentary on the fact that, if anything horrible happens to us, it is 1) our defining characteristic to breed violence and 2) our own fault. It's a good lesson with a clumsy execution. I want this message to work. I really do. I get, from Boyle's perspective, that his films are meant to have themes that challenge us as people. But the movie already deals with a lot. This idea is really lost in the barrage of other concepts that the movie tossing around. When that concept is lost, it really just comes across as silly and almost like a lyric from a heavy metal emo song. Conceptually cool, but the rest of the film makes it look phenomenally stupid. I don't know why I didn't pick up on it before. Probably because I was in college and loved Moulin Rouge!, so subtlety was completely lost on me. There's going to be a lot of talk about zombies in this and the role of zombies. I just finished a whole presentation on Monster Theory, so it's probably going to show up a bit. The Walking Dead has so influenced this generations understanding of the role of the monster. After all, I think that there's straight up a line where maybe Rick says, "We are the Walking Dead". It doesn't get any more on the nose than that. Romero is clearly a fan of allegory. It's kind of what ends up hindering him the deeper he got into his films. The allegories of Night of the Living Dead and Dawn of the Dead are so spectacular that I got the vibe that he wanted to recapture that magic anyway he could. The one thing that zombie movies need to understand that zombies aren't necessarily the antagonists. They are part of the setting. When zombies become part of the setting, it does a bunch of things that 28 Days Later totally gets. If we're looking at Maslow's hierarchy of needs, shelter is so fundamental to people that complex ideas like emotion and love become deprioritized. This means that characters, who are still experiencing these moments, can't include reason and logic in those emotions. Secondly, if the zombies are part of the background and the setting, another antagonist must step in. I think in 2002 when I was watching this movie on repeat, I didn't really understand why the soldiers were in the movie. I thought zombies were cool and "Didn't this movie look cool with its VHS chic?" That's it. That's the extent of my thought process. But the human beings are far more telling of the evils of a zombie apocalypse. Boyle is extremely critical of both people and the military. There's something wired into soldiers that parallels the zombie rage that's going on throughout the story. (Again, I think rage is dumb, but I can't deny the connection that Boyle is making.) Boyle's commentary on the soldier might make some people angry, but he's also making a pretty solid point. For someone's career, they're taught absolute violence and absolute trust. This is fine when there is a strict sense of rules and morality provided to people trained to kill. The military, besides training soldiers to be weapons of war (and, to satisfy the political spectrum, bringing peace and civilization to ravaged countries), also provides for the needs of the individual. It's very dependent on a great system being in place. However, when that system collapses, something very scary happens. The soldiers in 28 Days Later are the new zombies. We don't associate them with the zombies (I know the movie uses the word "infected", but I don't care that I'm using the shorthand) because they speak and are originally introduced as characters providing hope. But there's something really telling seeing the zombie soldier chained up on the fence. That image is that crossover into metaphor. This was a man who probably did a lot of good. But without a morality system, this character becomes something really problematic. Watching the way that the soldiers act to simple hierarchy of needs once again is really telling to what is happening in the overall story. These characters needs are in different places. With the survivors, Jim, Selena, and Hannah, they are there for survival. There's no thinking beyond that point. It's kind of why the kiss happens when it doesn't really make a lot of sense that these two would be into each other. There's no logic. But the soldiers have shelter, food, and a rudimentary sense of security. (Admittedly, that sense of security is misplaced, but that's another story.) But the survivors have the potential to have all of their needs met, given time. The more that they work together, the closer that they get to having their needs met. Discovering the grocery store is something that satisfies one of those needs, allowing Jim and Selena to explore that sense of intimacy. But the soldiers never have a chance for having that sense of intimacy met, so they become toxic and like the zombies. This doesn't let them off the hook morally. If anything, it's quite damning for these people. Because they aren't willing to sacrifice any other of their needs (like becoming a civilian and sacrificing security), they aggressively hoard something horrible within themselves. There's actually the example of the one solider who has a clear head on his shoulders. He becomes this voice for the potential of the solider. Soldiers, as individuals, are good people. However, if that individual cannot recognize his dependence on the institution, he becomes something far more evil. Boyle doesn't make movies just for fun. These characters are something far more interesting and insidious than just scary bad guys who become raping and killing machines. They are the real zombies in the story because they can't change their traits any more than the zombies that acts as foils to these characters. So, yeah, rage infected monkeys are dumb. But there's something that Danny Boyle is trying to do with that idea that could work if it was massaged a little more. There's a lot going on with this story. It adds to the greater narrative of the canon of zombie stories and their goals. Sure, the movie might look different than some of the other films in the fraternity of zombie films, but it uses satire as a means to comment on a war-obsessed 21st century. Rated G for flagrant sexism and abusive relationships. It's G because it's adorable, okay? This might be one of those things that subconsciously plants images of worth into kids' heads. But realistically, it's mostly just a cute movie about singing and hilarious accents. That's most likely the big takeaway, but I also don't have a masters in psychology that would tell me if something screwed up is happening upon watching My Fair Lady. G.

DIRECTOR: George Cukor I keep watching this movie and I keep cringing at Rex Harrison. Listen, I think we all like the idea of Rex Harrison. But Rex Harrison can't sing. He can speak sing. He can almost character sing. But the thing about commenting on My Fair Lady is that you are kind of comment on George Bernard Shaw and the entire Pygmalion myth. There are things that I really enjoy about My Fair Lady. But on the other side, I keep trying to like and it have lots of reasons to not like it. I normally love to stay on the side of classics, but My Fair Lady might be that bridge too far in a lot of respects. What is the message of My Fair Lady? I love virtue signaling apparently because that's what I do on this blog. But My Fair Lady presents a bad guy as a hero and knows that it is doing it. Henry Higgins is absolutely terrible to Elisa. The movie comments on it the entire film. The song "Poor Professor Higgins" is sung ironically. I get the idea that Cukor and everyone involved in every version of My Fair Lady gets that Eliza is the victim of this story. She vocally hates Higgins for his cruelty. He treats Elisa as subhuman and only falls in love with her despite himself. It takes the majority of a very long film to realize that he's in love with Eliza. "I've Grown Accustomed to Her Face" is actually a pretty damning realization that his indication of love is that "I'm used to her." Yet, Eliza falls in love with Higgins. Listen, I also have a problem with Beauty and the Beast, so I'm equal opportunity white knighting here. There is a song where Eliza daydreams of killing her captor. While Eliza may have gone to Higgins for elocution lessons, she had no frame of reference to the severity of the entire situation. There's a very clear line between "intense" and irresponsible. This isn't a boot camp she is signing up for. Boot camp is intense, but it is because the instructors need the recruits to survive training. It is done for the benefit of the soldier. That seeming cruelty is for a healthier goal. With Higgins, Eliza is clearly relegated to subhuman. She doesn't get any rights and abandons her personhood to laboratory science. While that bath scene plays out as very funny, it is aggressive with how little Eliza's intentions are taken into account. As a teacher, it's kind of horrifying. My students' parents pay tuition to go to my school. In no scenario am I allowed to grab a student's hand and force him or her to do work. While the bath may be towards the mutual goal of making Eliza Doolittle a lady, there is no understanding of the process, nor is there empathy for the confused Eliza Doolittle. I remember a few years ago, when A Dog's Purpose was coming out, that people were up in arms about the dog being forced into water. I rolled my eyes a bit because I'm a bad person, but the same thing is happening in that scene with Eliza. Yes, Eliza is fictional. But she also has capability of reason and a complex emotional spectrum. The movie is wholly aware of this. It offers Pickering as the voice of reason and humanity. He constantly comments on Higgins's cruel actions, but does nothing to really stop it. It's all for the greater good of having a romantic storyline. This is one of those romantic stories that is utterly confusing. And I even know why it goes on like this. The message of the story should be that they improve each other. Higgins offers Eliza something that would give her a life outside of her limited station in life. This is all assuming that Eliza's life would be better based on economics, but I'm going to let that one slide. But the contrast is that Eliza has somehow made Henry a better person. I don't know if that's ever really proven. She gives him a point of pride, which the movie also scorns. It's like the movie gets all of the evil that is going on throughout the film and utterly says that the world should be that way. Really, the ending is just that Higgins gets everything. Eliza becomes almost domesticated by Higgins and that Higgins treats Eliza like a pet at the end. His apology is pretty weak all things considering. He never really admits fault, but they both slyly comment on the idea of slippers and the way that things are going to be. It's just a really inappropriate joke. But at the end of the day, these things are all jokes. I know I'm taking this way too seriously because I don't actually hate the movie as much as it sounds like I do right now. It's just that this movie really seems way too self-aware to be promoting the ending it gives. Listen, the movie is three hours long. It's a tank. It has an intermission and everything. It's really because there are a lot of songs and a weird, unrelated side plot about Eliza's father marrying his long time girlfriend. What if some of that time was focused on the development of Henry Higgins? Some people might argue that Higgins does indeed change throughout the film. If he does change, it is through baby steps. My main example is the fact that he doesn't acknowledge Eliza's growth at the ball. He sees it completely as his own victory. Similarly, he is angered when Eliza finds a much more appropriate match for herself. When he confronts her, his primary argument is that Eliza is doing him a disservice. I kind of think My Fair Lady is a bit gross. I know. It's a comedy and it's old timey. But it seems like everyone knows the right thing to do, but they sacrifice it for the greater joke. The takeaway is that Eliza Doolittle has tamed Henry Higgins, but I don't know if the movie really effectively sells that concept. I know people love this movie, but I'm very meh on it. And I still do blame the casting of Rex Harrison. (There's a solid chance that a better singer might get me to ignore the troublesome narrative and I acknowledge my own hypocrisy.) Rated R for all the sex. Like, if you were wondering if a movie from the '80s named Body Heat had any sex and nudity in it, it does. I mean, I suppose it seems moot to point out that it has language as well. There's also murder! And the destruction of property. But who cares about any of that? It's all about sex and sweating and sweaty sex. Just a heads up in case you were wondering "Is this about a fever?" Not the kind of fever you're thinking of. Intense R.

DIRECTOR: Lawrence Kasdan I swear, it was for my class! Yeah, I knew about Body Heat before this moment. But it was never really on my list. In fact, now that I've seen it, I can only classify it as "Okay." It's Lawrence Kasdan directing. Do you understand how insane that is to me? I saw his name pop up in the opening credit and my jaw dropped. This is very not-Lawrence Kasdan. Sure, film scholars would completely disagree with me. But I can't divorce Lawrence Kasdan from the summer blockbuster. He's just that guy in my head. He is involved in the making of some of the biggest movies ever, so to see him do this tiny kinda/sorta remake of Double Indemnity only with a lot more sex is insane to me. The '80s were so unnecessarily sexy. I know. This isn't adolescent Tim, who probably would have been destroyed by this movie. This is happily married Tim who has three kids and gets a little sleepy if he eats a carb. The first sexual act, I gave my wife the eyebrows. We giggled and then settled in for a lot more of the same. No eyebrows...just a lot of sex. I'm going to attack this movie pretty hard, considering that I left thinking that the movie is halfway decent. But I want to comment on how Body Heat may have been instrumental in the lazy sexual thriller. Double Indemnity is the same story. I don't think anyone, including Kasdan would deny that idea. Spider Woman traps man in a web of sexuality to convince him to kill her husband. With Body Heat, Kathleen Turner's character (whom I refer to as "Kathleen Turner" because of the questionable naming situation within the movie) is a lot more sexually aggressive than Phyllis, mainly because this is made in the '80s. But Double Indemnity, because it had to keep its sexuality in check, had to do all this other stuff to compensate for the time that would be otherwise occupied by people having sex on screen. Body Heat, because it's 1981 and my parents' generation clearly were a bunch of horndogs, were okay with constantly filling the screen with sex. I am going to stop virtue signaling for a second and get off my high horse. From an artistic perspective, it's exciting to know that the film is in a generation that can say what it wants to say without having to tip toe around the film. When Barbra Stanwyck's feet are showing in Double Indemnity, it winked at the camera and titillated audiences just enough. But I'm sure Billy Wilder felt like he had to make sacrifices in the name of censorship. Body Heat kind of reads as an alternative history, playing out what Wilder might had wanted to do had he been granted the creative freedom to do so. But so much of the real estate of the movie is the two characters having sex. Inadvertently, despite that I kind of respect Kasdan as a director in this, he establishes a formula for the sexual thriller. Body Heat is pretty bare bones in terms of beats. There's the seduction, the murder plot, the murder itself, the revelation, and the betrayal. But really, if I was to put all of that into a pie chart, the majority of that real estate would go towards the seduction. At one point, there's an element of "We get it. They're sleeping together and it's very warm outside." It's probably one of the more memorable scenes in the movie, but it was a bit much for me. Again, I'm going to go into spoiler territory, so I apologize for that. The entire premise is that Kathleen Turner is seducing Ned from the word "go." The first time she's on screen, she's already deep into her plan. There's a real plausibility thing going on that we kind of see in movies like Skyfall or The Dark Knight where the villain is just too good at everything. Her big plan is to seduce Ned (HIS NAME IS NED!) and get him to kill her husband. There's a lot of loose ends in this plan that I do not care for. But let's assume that the plan starts going off without a hitch. She has to allure him so much so that this serial philanderer keeps coming back and that he needs her. (Why go after a type that hates staying with a woman?) She plays so hard to get that he takes a chair and breaks into the house. This is all part of her plan. She locks him out and stares at him until he makes his move. It's super passionate and sexy...but also super impractical? The point is to both seduce him and not to let anyone know that there's an affair going on. I know the husband is only out there once a week, but your glass guy is so on top of things that you can afford to have a giant hole in your house and a bill for glass repair? It's sexy, but stupid. This all ties into the idea that sexy covers up for stupid. I am embarrassed to make this leap, but I feel like Body Heat has more in common with Species than it does with Double Indemnity, at least tonally. But Body Heat isn't a dumb movie and it isn't the first movie to really try the plausibility factor for how far a character would go to get what she wants. I kind of love what the ending does for the movie. I'm going to complain about one thing with the ending, but I'll try to steer the ship back. The ending sees Ned figure out the scheme. The boathouse is rigged to explode and Kathleen Turner fakes her own death. But also, she really didn't plan to fake her own death. She planned that Ned was going to walk into the boathouse and the corpse of her friend and Ned would be found as a joint suicide or accident or whatever. When she blows up the boathouse, how does she survive? Besides the fact that she got close enough to detonate the boathouse, did she have a boat? Did she swim somewhere? It's very much in the same ballpark as the door through the glass, but I digress. I do love that she gets away with everything. Classic film noir always had crime being punished. From Ned's perspective, he is punished for his crime. But because Kathleen Turner gets away with it, it creates something very different. Her escape leads to the idea of the sexual boogeyman. It's an idea that's explored a few times in cinema history. When it is done well, like it is in Body Heat, it's dynamite. Her escape and loose ends kind of makes the story like a bedtime morality tale. We've seen stuff like this in Keyser Soze in The Usual Suspects. It implies that Kathleen Turner is out there and will do this again. She is so many steps ahead of every character that the only way to prevent what has happened happening to you is to keep it in your pants. It's Jason Voorhees, only way less blood. It's a haunting idea, this almost omniscient villain. Yeah, we're all sitting here thinking "Malarky". I'm actually probably putting words in other people's mouths. The other people in my class were very cool with these perfect plans coming about. While I would have loved a bit more crafting when it came to generating these plans, I do like the effect of it all. Ned, bearded and communicating his theories at the end, is a satisfying end that is absolutely terrifying. It's a hard ending to pull off because, ultimately, Ned does deserve his fate. He did murder someone in cold blood and for selfish reasons. But we also know that this was the plan all along. Ned embodies both the role of criminal and victim. He is worthy of sympathy, but a lack of punishment for his misdeeds is a miscarriage of justice. It's a pretty great ending. The only problem with the movie, for me, is that it is only about fifteen minutes worth of actual storytelling. The lion's share of the movie is the sexuality. We really only need one sex scene in the film to really tell the story. Normally, you could argue against me saying that the sex stuff is really necessary. But because it is a spiritual remake of Double Indemnity, we know that there's so much more that could be explored. Ned, as a patsy, makes him a shallow character throughout. It's actually pretty silly that Ned vocalizes that he wants to kill Kathleen Turner's husband because he doesn't really have that built into his character up to that point. But Ned almost doesn't need to be well developed, despite the fact that he's a protagonist. The entire movie is about how he is a pawn and that's exactly how he's portrayed throughout the film. As much as I dunk on this movie, it's objectively pretty genius. Yeah, I whine because I can. I won't watch it if I don't have to, but that's because I'm happily married and softcore sexuality seems odd to me in films now. Also, there's a chance my wife might be reading this and I want to score some points. PG for scary stuff, I guess? I mean, the guys fight a dragon. There's a lot of other things that could kill them, but that's pretty mild I suppose. I feel like every Disney movie has some degree of peril at this point, so PG should be for all Disney movies. I can't even think of anything that has innuendo. I would like to say that the PG surprises me, but it doesn't. But I also can't think of a straight up G rated movie at this point for 2020.