|

PG, but the allegory is just there on the screen, man. It's got the same thing that Zootopia has going on. Seemingly a fun story about hairy babies singing about stuff, the entire film is a strong message about being an anti-racist. I'm all for that. I loved Zootopia for doing that. I love this for doing the same thing. But I know that a lot of parents might feel icky about the preachy factor being lined into kids' movies. Being all for it, I tend to encourage this kind of thing. But I also know that this movie may require a heavy discussion after watching it. PG.

DIRECTORS: Walt Dohrn and David P. Smith How is it that I really dislike the first entry and completely get on board the second entry? Seriously, the first Trolls movie would play in our house on repeat for months after it hit home video. I'm not going to read my thoughts on the first movie right now. For all I know, I was positive about the movie. I just know that, after multiple viewings of the film, I find that movie to be grating and annoying. It's got a really weird message and I don't want to hear the same snippets of songs again. I don't know why I was down to watch Trolls World Tour though. I think it was because it seemed fairly new and it was on Hulu. Like, I felt like I was cheating the system by distracting my kids long enough for this to hit one the streaming services we were already paying for. But Trolls World Tour kind of made me turn my head and take it seriously, considering it still is a movie about big haired baby people who sing. If I get politically charged, it's because I stayed up and watched the debates last night and I realized how terrible things have gotten in this country. Sorry if that bums anyone out, but considering that Trolls World Tour (with a name like that, how can you not appreciate the irony?!) is about anti-racism, I can't help but get intense. While I will always hold Zootopia as the pinnacle of challenging kids' movies, Trolls World Tour might get my second place. The thing that really works about Trolls World Tour is that it really sneaks up on you. I think a lot of that comes from the fact that the first film is just so vapid and empty, that when the seeds of racism are being discussed, I had to question what I was watching. My mental narration was, "Wouldn't it be crazy if the music represented cultural appropriation and not-seeing-race?" And then I scoffed at that, thinking that Dreamworks didn't have the guts to do that. But as the movie kept going on, I kept seeing those seeds getting fed and there were more and more things that really sold the idea. It's such a complex battle that the movie fights for. I mean, there are levels here that I wasn't prepped. The message I always had growing up was that we were one global community. There's something valuable about viewing civilization as human first and cultural / racial second. But it also is an overly simplistic and demeaning idea to think that people shouldn't celebrate their differences. Using the metaphor of music (which could get pretty touchy, the more I think about it), World Tour sells the concept that so much about what white culture views as open-minded is simply the recurring concept that white people aren't monsters. You did get that the Pop Trolls represented white people, right? Because the movie straight up calls out the Pop Trolls for the concept of institutionalized racism. Yeah, the Rock Trolls (it's very odd to be writing this, by the way. Just sympathize with the surrealness I'm dealing with right now for a second) are the clear bad guys. By using violence to spread their own culture, it harkens back to conquistador culture and the de facto segregation of cultures. Because the Rock Trolls view their music as superior, the other types of cultures / musics must therefore be inferior. I won't deny that this bummed me out because I was jazzed (pun intended) to hear some music that wasn't pop with this film. I probably sang along with the Rock Trolls more than I'm comfortable admitting to. But the idea that everyone else has to conform to the most powerful aggressor's cultural norm is the toxic, visible threat makes the secondary threat all the more troubling. When it is revealed that the Pop Trolls were the first group to attempt the Rock Trolls' plan, there's something to be said about the rewriting of history to comfort the aggressor. Poppy and her tribe live a pretty charmed life. (Or since they're the Pop Trolls, you could say "Semi-Charmed Sort of Life".) But that comfort stemmed from the idea that they thought that they were the superior tribe. It's a really weird gag when Poppy's father tries hushing the whole thing up and claims moral victory over the happy ending, but it is a kids' movie. But that realization that absolute unity isn't necessarily a good thing. People have voices and cultural beliefs that should be respected and not appropriated. The idea that these cultures should be respected for what they are, while maintaining healthy relationships is probably a better idea. Not everyone should be what White America considers the norm. It's appreciation and respect, not co-opting a culture to make the self feel comfortable. Because the message of Trolls World Tour is so overt and central to the film, the actual mythology of Trolls might not be serviced as much as it should though. I know. I am also reading the sentence I'm writing and question everything I'm doing with my life. But the movie sells a couple of major plot points for the characters to grow. Poppy is so obsessed with being seen as an effective leader. Branch is in love with Poppy and he doesn't know how to tell her, especially when she is making mistakes left and right. James Corden's character, for some reason, feels betrayed. These are all storytelling tropes that feel distantly second compared to the central message. While there is a bit of a disjointed tie to the central theme, it does require a lot of heavy lifting for the viewer to get to these moments. They don't come organically. But Trolls World Tour is great. Yeah, I know a lot of parents don't like message movies, especially ones that tie into politics. But if we're going to ask our kids to be better than we are, stories like this might be important. It takes a complex concept and makes it relatable.

0 Comments

PG-13 for forty years of Bond family-friendly sexuality and violence. Per usual, James Bond tends to sleep with a lot of women and kill a lot of dudes. Possibly the only questionable content on top of that comes from the fact that James Bond is tortured for the beginning of the film. Also, we get to see slightly more blood than usual due to recurring sword fighting sequences. There's also all kinds of filthy jokes. I don't know if any of them reach the one I think of with The World is Not Enough, but they are pretty overt.

DIRECTOR: Lee Tamahori Oh man. I have been dreading this one and dreading this one. As quickly as I started the Brosnan era of James Bond, it would fizzle out in what I clearly think is the worst Bond movie ever made. It's so rough, guys. It's so rough. It's not like all of the James Bond movies are absolute winners. I know it was kind of pulling teeth for me to sit down and rewatch some of the rougher Roger Moore entries. But Die Another Day is in such a different level of bad that it really burned out my obsession with James Bond. That's even considering that potentially the best Bond movie is next, that is kind of saying something. While I can't free the producers from their responsibility with this movie, I do think a lot of the problems lie squarely on the director, Lee Tamahori. There's some choices being made with this movie. Perhaps Tamahori is the child of 2002, an end of an era that I consider the Mountain Dew of filmmaking. Everything in 2002 was angsty and stylized for the worst. The Matrix had done amazing things for science fiction, but stylistically tainted every action movie that would come out for the next few years. Die Another Day was released as the 40th Anniversary celebration of all things 007. It was the twentieth Bond movie on the fortieth anniversary. Expectations were that Die Another Day was going to bring Bond into the new millennium while paying tribute to all of the movies that paved the way. For director Lee Tamahori, I think that meant "Lean heavy into the spy-fi and have stylized edits. But there's nothing at all special about Die Another Day. It is overloaded with really bad references to each Bond movie that came before it. (Some of the references are stretches or just plain old lame.) But instead of focusing on making a good Bond movie or something that would change the world of Bond forever, the story becomes easily one of the most forgettable in the series, mainly because it is just an homage / rip-off to Diamonds are Forever. There's something to be said about being beholden to the past. There's a really fine, but important, line between nodding to the past and straight up addressing it. Because the movie is so drowning in the past, it kind of treats Bond history like Austin Powers does. Rather than viewing forty years of Bond filmmaking as revolutionary long-term storytelling, it strips away any degree of complexity to simply the Bond tropes. What Die Another Day leaves us with is heavy, heavy spy-fi. The spy-fi stuff in Bond might be the worst. There's a reason that the Craig movies shot for a more grounded foundation for the films. Gustav Graves' mech suit is over-the-top stupid. Couple that with really bad electric special effects and the movie just has nothing to stand on. I guess this kind of spirals into the moment where my love for Bond died. In my World is Not Enough blog entry, I talked about one of the worst deliveries of a line in cinema history. (Again, my apologies to Denise Richards for my long diatribe.) But the use of CG in this movie is a travesty. The 40th anniversary is meant to be a celebration of Bond. As part of that, it should also be a celebration of stuntmen and the risks they take. I'm talking about Bond surfing down a glacier here. This is a scene that has two separate surfing action sequences. (Yeah, I just realized that too.) But the second one, where Bond converts the hydrofoil into a surfboard crosses a big line. One of my favorite action sequences in Bond history comes from The Living Daylights. The rear of the cargo hold is open and Bond is holding onto netting for dear life. The sequence is homaged here with the helicopter coming out of the plane. Uncharted 3 also did the same bit. But in The Living Daylights, Dalton's stunt double is being whipped around and that scene is genuinely suspenseful. I know that James Bond is going to make it out of there alive, because it is a James Bond movie. But with the surfing down a glacier scene, it doesn't even have an uncanny valley feel. It just feels like watching a video game. There isn't a moment of investment there at all. I know that no one is really doing the stunt. It looks like someone just copied and pasted Pierce Brosnan's head onto a computer generated model. But most importantly, and I've always felt this about Die Another Day, is that if a real person can't do the stunt, James Bond can't do the stunt. That's a weird logic that I want to explore. I get that one stuntman isn't doing all of Bond's stunts. He has a team that specialize in each choreographed sequence to ensure that the stuntman can leave the scene unharmed. But the idea that someone is really doing that action in the moment gives us that element of fantasy that we need to imagine one man doing all of these stunts. Yeah, James Bond should have been dead ages ago, considering the things that have been thrown at him. But when Bond starts surfing down a glacier, it completely pulls the viewer out of the fantasy. No one could do that. It's the bridge too far. We can't be expected to have an emotional attachment to the impossible. Halle Berry is wasted on this movie. I honestly don't know how they got her to show up for a film like this. Maybe it was the prestige of being part of an anniversary? But Jinx might be one of the least developed Bond girls in the franchise's history. Say what you will about Miranda Frost, at least she has some motivating characteristics. Miranda Frost is supposed to be the secondary Bond girl. She's there for the plot and that's it. But Frost is way more compelling than Jinx. Part of it comes from the fact that her lines are eye-rolling bad. I've heard Berry complain about a lot of her roles being poorly framed and I don't think it ever really gets worse than Jinx. Why Gustav Graves? There's a line in the movie where Colonel Moon says that he based Gustav Graves off of James Bond. I mean, he has to instantly retract that by saying "Just in the details". But there's almost nothing about Toby Stephens and his weird sneer that come across like actual Bond. If you squint, I suppose he might look like a passable Roger Moore. But Graves is possibly one of the most vanilla bad guys in the franchise. Bond villains are fun to play and they should be horrifying and scary. Graves, as a commentary on Bond, doesn't work. It's a strong misunderstanding of what the character is about and it just sucks. The funny thing is, each time I watch Die Another Day, there are elements of a decent Bond movie. The first half isn't that bad. I know that some people would be mortified to know that Bond is captured early on and tortured for over a year. But that's very Ian Fleming and I think it makes sense. It's just odd that the movie wouldn't embrace that element in the movie more. That year should have had psychological repercussions on the character. Skyfall would eventually learn from this mistake and play up the idea that Bond can't always be perfect all of the time. There's something to be explored. But when a self-given haircut can wipe away years of abuse, that's pretty weak. This movie should have crushed and it continues to be a disappointment. It's so bad because it is at the hands of people who don't really understand what Bond could be. It embraces formula over substance at every turn and took one of my favorite Bond actors to a low point. PG-13? Really? I honestly thought it was pretty R rated. I mean, the movie is aggressively talking about underage premarital sex throughout the story. It hits on some pretty dark territory. There's language all over the place. Because it is Diablo Cody, perhaps the language is not traditional cursing. But it still really has the vibe of pretty vulgar language. It isn't exactly an easy movie to get through at times. But PG-13 is PG-13. There you go.

DIRECTOR: Jason Reitman What is Diablo Cody up to? I mean, I have the Juno IMdB page up. It's really just a click away from having answers. It just feels like so much...work. I remember when she was having her heyday. It seems like she was attached to every project because of Juno. But in 2007, I was 24. This was a very different movie for me. I was obsessed with merely the language and the aesthetics. I mean, this is a movie that still wildly entertains me. But I'm not sure if this is an aggressively pro-life movie or if I simply imbued the film with that attitude. I always sold Juno as the most subversive pro-life movie ever made. But I probably need to play Devil's Advocate if I'm going to be at all attempting objectivity. Pro-choice doesn't mean that all unwanted pregnancies should be aborted. This is such a heavy topic to talk about, but it is at the center of the film. Juno, when she visits the pregnancy center, is there to get an abortion. Her step-mother, Bren, even asks if she wants to get an abortion. The roots of the pro-choice movement are really concretely established in the film itself. Juno and Bren don't come across as morally bankrupt in these moments. Rather, it is something that is part of the narrative that the movie pushes. I really don't get the vibe that Diablo Cody is vocally pro-life, so I have to take all of this into consideration. But it is pretty telling that Juno's reason for leaving the pregnancy clinic before receiving an abortion because of Su-Chin's protest. It is the connection that Juno makes that the baby has fingernails that causes her to turn around and hold onto the child. While I'm not an expert at the pro-choice argument, one of the thoughts is that the mother imbues the fetus with life when she chooses. I dismiss this concept, but it is kind of marvelous that Juno, with the realization that the baby has fingernails, that she is carrying a living person inside of her. In this moment, she has this shift in philosophy and belief. This one is going to get preachy and I apologize, but that's a really big shift. Because the baby has fingernails, there's the epiphany that the baby is actually a baby and not a fetus. But then Juno comes to a greater awareness. Not only is the fetus a baby and the baby has fingernails, but that there are people oh-so-desperate to have a child. It's great that they find the parents in the Pennysaver, but the abstract idea of infertile couples becomes real. Yeah, they are deeply broken people. Vanessa, for all of her positive parental traits, has lost sight of her marriage. Mark, the far more toxic element in the marriage, is so self-centered that he wants to seduce this high schooler because he feels like he hasn't gotten the attention that he desired. But the idea is completely sound. Vanessa, as is stressed throughout the film, would make an amazing mother. She has tried and tried and is barely holding onto hope to be a mother. Reitman and Cody build this vulnerability into her. She is a woman who keeps taking a beating in her marriage and keeps pushing on. Yeah, Mark is tired, but he's also part of the reason that she's falling apart. One of the key arguments in the pro-life movement is that there are just couple upon couple waiting to adopt a child, but the world has made it so hard to do that. But the pro-life movement isn't exactly given a free pass with this film either. If the central conceit lies in the idea that Juno is carrying this baby for this couple that can't have their own, the way that she is treated through the course of her pregnancy is pretty damning. As much as the movie is about a twee upstart carrying a baby and speaking her own language, people treat Juno like dirt throughout the piece. The administrative assistant gives her the side eye when she's late for class. The abortion clinic receptionist has a hard time sympathizing with her. Even the ultrasound tech can't set aside her prejudices because that's what we've been taught as a culture. If a girl gets pregnant, her secret is out and she is deserving of scorn. Again, I'm pretty pro-life, but we're far from the nicest people about being open about sin. As annoying and petty as Juno is at times in the movie (it's forgivable, she's a teenager), it can't be ignored that Juno is doing something completely holy in the act of carrying this baby for this couple that can't have it. I don't know what to think about Paulie Bleeker. Besides the fact that I can't mentally separate Michael Cera from Jason Bateman in this movie, I don't quite know the message the film is sending about Bleeker. Bleeker ends up being the perfect boyfriend. He's never really meant to be vilified by the film because Juno ends up with him in the happy ending. But Bleeker is frustrating and sympathetic simultaneously. I suppose he might be the problem with the "nice guy" character. With Juno being such an alpha character, Paulie Bleeker often comes across as a little of a wuss. He continues to lead a care free life, comparatively, with his running and his orange Tic-Tacs. But we know that he both should and shouldn't fight for investment with this child. Part of the issue with breaking Bleeker down as a character is that Juno doesn't really let us connect with him in a situation that gives him any real power. Juno recommends that Bleeker starts dating Katrina DeVoort. He states his disinterest with Katrina because he makes his intentions with Juno fairly clear. When he actually goes to Katrina, we're disappointed because he's not with Juno and because he clearly doesn't like her. But more than that, we are angry with him because he's moving on with his life and leaving Juno behind. But that's what makes the repair of that relationship all the more cathartic. He gets the right level of investment that Juno is comfortable with and is able to be vulnerable as well. I love Juno's parents so much. Besides the fact that they are being played by J.K. Simmons and Allison Janney, they really balance this line between profound disappointment in their daughter's choices and sincere admiration for being to undertake this Herculean task as her age. It's so funny now that I'm an old fart that I find that I relate far more to the old farts than I do the hip young kids. There was a time that I questioned Juno's hamburger phone as something the kids would do. But I kind of let that go and focused on all of the adult characters. I looked at the toxic things that Mark was offering and the temptation to hold onto youth. I saw elements of Vanessa in my wife (the good stuff). The entire film made me wonder which kid was going to drop a huge bombshell on me and how I was going to handle it. But that's kind of what makes it a good film. Cody and Reitman made this film that, yeah, is super twee. But they also populated it with characters that made us sympathize and ignore all of the window dressing that the movie offers. Juno is one of those movies that I really like. Yeah, it gets into heavy material. Sure, sometimes it feels very self-conscious and desires to cover up flaws with hipster wit (I also really like Gilmore Girls for the record). But at its center is a story of a scared young girl who refuses to be vulnerable, despite the fact that she is sacrificing a year of her life to ensure that a couple has a baby. That's pretty great. Rated PG-13 for all of the scary stuff involving The Beast. I mean, Split was PG-13. Unbreakable was PG-13. If Unbreakable could potentially water down the very disturbing Split, I can easily see this movie being PG-13. There is some blood and there is some very troubling violence, especially the casual murder of hospital staff. Death is something that isn't absent from this world, so major characters are at risk. Similarly, Mr. Glass's condition means that you have to get comfortable with seeing broken bones on both the adult and flashback versions of Elijah. PG-13 is pretty accurate.

DIRECTOR: M. Night Shyamalan When I was real young, when only the OG Star Wars trilogy, pre-Special Editions, existed, I remember that we would talk about the things we heard about the future of the franchise. When the VHS tapes started listing the first Star Wars film as "Episode IV: A New Hope", we started gossiping. "George Lucas will probably make a prequel trilogy and a sequel trilogy." When I was in high school, I remember similar voices murmuring about a potential Unbreakable trilogy. We knew that Unbreakable didn't have the box office to carry a franchise, but we hoped. The ending of Unbreakable meant that we were going to see the poncho man fighting super villains and it was going to be awesome. Well, it's 2020. Besides the fact that the sky is Blade Runner red now and I'm borderline teaching with a biohazard suit, there are a boatload of Star Wars movies and now we finally have the trilogy of Unbreakable movies. I mean, when I found out that Split was a secret sequel to Unbreakable, my hopes were raised pretty high. I think it was Facebook that spoiled the end of that movie for me. It wasn't even my friends. It was some random algorithm that posted a link to saying "How M. Night Shyamalan made Split a sequel to REDACTED." It didn't take very long to figure out what that was going to be. But Split proved that there was something else to say about the role of superhero fantasy. The greatest part of Split is that we didn't even know that we were getting preached to. In Unbreakable, Elijah goes into this speech about how there are two kinds of villains. There's the physical villain, who is a challenge for the hero. But then there is the mental villain, who is the real threat. While watching Split, because Shyamalan never brought David Dunn into the equation until the last possible second, we have all of this focus on the origins of a supervillain. While not a perfect film (I still enjoy Unbreakable better), Split does right what every origin story does wrong. Most origin stories tend to devote so much time to the protagonist's origin story that it shortchanges the villain. Kevin / The Beast, instead, gets all of the attention. He's this force that drives the film. Which brings us to Glass, I suppose. See, those early rumors of an Unbreakable trilogy were true. Shyamalan wanted to have three movies exploring the world of Unbreakable. In the first film, he would discuss the psychology of the hero. In the second film, he would discuss the psychology of a villain. But in the third film, it has to act as a conclusion to this world. If the first two films are about the psychology of the characters, what new ground would Glass tread? The answer is...not much. What made the first two films so great is that they weren't about the glitz and glamour of superheroics. It was a world where superherodom was just being discovered and that's what was interesting? What would happen if the unimaginable fantasy realm started becoming plausible? When Superman rescues Lois Lane from a falling helicopter in Donner's film, it's this giant leap forward. We go from a world without superheroes to a world with brightly colored flying people. But Unbreakable and Split stress that the world is fundamentally the same, but slightly different. So when we talk about Glass, there's really nothing much more to say. I feel like Shyamalan is desperately trying to say something profound with this movie. The cool part is that the film does play with making the audience second guess everything that they know to be true. After all, these aren't established characters that we have been following for decades. It is plausible that we have been using our confirmation bias to want these characters to be special. But we as an audience know that stripping these characters of what makes them special is a profoundly disappointing and borderline impossible way to make a film satisfying. So if the first two films were about stripping away what makes a superhero movie a superhero movie, Glass is embracing everything that makes a superhero movie what it is. The problem is, we have superhero movies. We have amazing superhero movies now. We have superhero movies that make us question the value of cinema because they're so good. With movies like The Dark Knight and Avengers: Endgame, these movies have broken free of any pre-determined value categories because they are engaging. So when a movie like Glass happens, it seems kind of quaint. This is a superhero grudge match that just seems kind of piddly. Shyamalan has created a world where flash can't actually be that flashy. So a grudge match between David Dunn and The Beast is fun, but it really feels kind of anti-climactic. To do something bigger would be a betrayal of everything that went into making the first two films. But that's kind of what we need for the finale of a trilogy. The reason that a lot of "Part 3s" are lame is that they need us to rethink everything we've experienced going into what we've seen. It needs to imply that with the first two movies, "you ain't seen nothin' yet." But Glass is simply a watered down (pun intended) version of things we've seen in the previous two films. If anything, the movie turns some of the characters into caricatures of other franchises. It's so odd that this film is called Glass. I know that we find out that Elijah is the connecting thread between all of the major characters in the story. But that connection is really artificial. It's a connection because Shyamalan simply tells us that it is a connection. Also, out of the three big characters, Sam Jackson has the least to do in the film. He spends the entire first half of the movie faking being catatonic. But really, he's just being Lex Luthor. He's the villain who sews chaos for the hero of the story. He's a genius wrapped inside of an even bigger genius. That's a fun character in certain settings, but it also isn't the Elijah of Unbreakable. The Elijah of Unbreakable is a deeply sympathetic villain. While he knows that he's the villain of the piece, it's something that he feels is thrust upon him by fate. He is hesitant to be the villain because he knows the greater good of his actions. Because Mr. Glass is the villain of the piece, it is meant to prompt a rise in heroes. It's the entire Reverse Flash thing, but from the comics not the TV show. But Elijah in Glass is more concerned with being right. Unbreakable Elijah is on a crusade to awaken superheroes at any cost. Glass Elijah wants to see a good, old-fashioned superhero fight. He also has changed his theory. Rather than saying that there is one special hero and one special villain, he believes that there's a glut of superheroes waiting to be awakened. He wants the Marvel Cinematic Universe for the real world. It makes him really villainous, which is kind of disappointing. He becomes what Mr. Freeze is after a while. In Batman: The Animated Series, Mr. Freeze was this character who was completely sympathetic. But when he starts robbing banks over time and just trying to make the world cold, he became just like every other villain. Elijah in Glass becomes the later version of Mr. Freeze. Sure, his scheming is kind of cool and I love plans-inside-of-plans, but there's almost a cackling that happens when he's committing atrocities. When the first Matrix movie ended, Neo flies off. It is implied that he is going to liberate humanity from the prison that is the titular Matrix. We really don't need to know how he's going to do it. The ending implies that he's going to be successful. But the lizard brain within us really wants to see super-Neo fighting robots. That drive to see that happen is fun...until we actually see it. While I love that Split returned us to the world of Unbreakable, it wasn't cool because we got to see David Dunn fight The Beast. It was cool because Shyamalan had something cool to say about monsters. The super fight in our mind is always going to be cooler than the actual thing. (Okay, except for the Endgame final battle. That fight owns.) For all of its attempt to talk about secret societies, nobody really cares about that stuff. It's just fluff and an attempt to talk about some of the more obscure comic book tropes. There's nothing about the human condition that really allows us to latch onto anything. I want to talk about the death of characters. SPOILER FOR AN ALREADY SPOILER-LADEN BLOG ENTRY. The trio dying at the end is an attempt to put a cap on this franchise, but it just reads really wrong. Mr. Glass dying, that kind of makes sense. He messed with The Beast and it is an appropriate punishment. His death also reads like Moriarty's death on Sherlock: It was always part of the plan. That's fine. The Beast dying is a bummer, but it also reads like the early days of superhero cinema. But David's death is borderline stupid. It reads more like "Bruce Willis is done playing this part" than needed for the story to evolve. It is completely blah. It is one of the most bummer deaths in film because it really kind of comes out of nowhere. That secret society wasn't established. He dies in a pathetic way. There's nothing sacrificial about his death. And Elijah's cryptic comment "This is the origin story" is silly, because it doesn't really read like an origin story. Sure, it might awaken the world to the existence of superheroes, but that doesn't make it an origin story. (I suppose every story is an origin story for someone.) Death should have weight and David's death just feels blah. Also, if Shyamalan is obsessed with his own made up rules about comic book tropes, why doesn't David resurrect? I mean, even Zack Snyder got that right with Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice. A hero never dying is so central to comic book formula that his death just seems to spit in the face of what the first two films are saying. David nearly drowns at the bottom of a pool as a child, and comes back. So, this time he drowns in a dirty hole. What is the message of that? But at the end of the day, Glass is more watchable than people make out. The thing I was saying about "Part 3" is that I always enjoy the movie for the spectacle of it. Yeah, they tend to be pretty weak in a lot of cases, but there's still time with characters we like. I wish that Glass had more weight, but it is completely a watchable film. Shyamalan is a pretty talented filmmaker who is always trying to mine the same well. The more he returns, the weaker he gets. PG-13 for a lot of off-screen carnage. Like, the death reach the statistics level. We don't see much blood or violence, but we're told about a lot of death. Also, the movie is intensely bleak. At one point, a child points a handgun at his father thinking that he is bulletproof. The protagonist also has flashes of people's evil deeds. Some of these get pretty intense. Part of me thought that the kids could watch this, but it really isn't a family friendly movie. PG-13.

DIRECTOR: M. Night Shyamalan "They alive, d*mmit!" Sorry, I can't think of the title without going right into Kimmy Schmidt. It's not this movie's fault. Kimmy came way after Unbreakable came out. But that theme song is just aggressively catchy. I wasn't supposed to rewatch Unbreakable for a long time. I have an oddly specific method to which movie comes next. But Glass was next on my queue, and it had been some time since I've seen the first in the trilogy. So I threw this one in. Now, for a long time, I claimed that this was one of my favorite movies. I was the kid who took the controversial stance to say that Unbreakable was better than The Sixth Sense. I bet this movie ages better than The Sixth Sense at least, probably because of the comic book film boom that we're currently experiencing. But I knew that I needed a refresher on the OG entry in the series before I really approached Glass. It totally holds up. It's better than I remember. Unbreakable was always one of those movies for me that I aggressively recommended to people, secretly knowing that that they would probably hate it. It makes me a bad person who desperately wanted people to like the things that I liked. But I realized that the reason that people didn't like it is because it is shockingly boring. For a movie about superheroes and supervillains, practically nothing happens in the film. Really, the central conceit of the film is that we never really know if David is superheroic or if Elijah is just playing the long con. But in my head, that's what makes the movie really interesting. I'm not saying that I need my superheroes to so grounded that we can't even tell if the film is a superhero piece. But I like the idea of applying a formula over a film that intentionally subverts formula. Everything Elijah says (which I want to talk about later) refers to the formula of comic books. While he's meant to sound like Campbell, he really is stressing that comic books aren't all that original. They tend to do the same things over and over again. His theory, the concept that comic books are simply transcribed history, is a little silly, but it gives the character a bit of gravitas. So when we're watching Unbreakable, we're really seeing how every day life applies to Elijah's (kind of made up) formula. I'm always worried about sounding like Elijah. I love Samuel L. Jackson in this role and none of the following things are a commentary on his performance. It is flawless. It's more about the writing. I am currently teaching John Lewis's March. As supplemental material, I'm showing the kids Robert Kirkman's The Secret History of Comics, specifically the "Voices of Color" episode. My entire grad school career was built around the notion that comic books are simply a form of storytelling and that they should be used in the classroom. Trust me, I'm well on my way to becoming a Mr. Glass. But Elijah never really reads as human to me at times. As much as I talk like Mr. Glass, I don't really respect his rules about the comic book. Shyamalan gives Glass all these lines about absolutes. "The villain is the exact opposite of the hero". "Villains have bigger eyes because they see the world differently." It's fun, but it's also kind of malarky. Sometimes, the villain is the opposite of the hero. I'm sure that some artist out there probably justified stylistic choices under the banner of artistic mumbo jumbo. But in a lot of cases, it's just the artist being the artist. Like, I want to jump on board and talk about the philosophy of superheroes, but it is just talking about tropes like they have deeper meaning. I feel like Bruce Willis always plays a crappy husband. I like how that is the center of David's personality, but we've seen him play this same part before. Heck, he even played it in Shyamalan's last entry before this, The Sixth Sense. There's this choice that Shyamalan imbues David with. He is always sacrificing what makes him special to be the quiet hero to the ones he loves. With Audrey, he intentionally abandons a football career to allow Audrey to feel a little more comfortable about David's safety. (Question: Why doesn't Audrey know he was faking? She was in the car and rescued by David, who seems perfectly fine when help comes.) But with his son, it almost feels like he is trying to hold onto a sense of normality so his son could have something safe with his father. It causes both of them misery. David wakes up every day feeling misery. Joseph feels gaslit. It's this cycle where the two end up keeping this secret together. But considering that secrets are what kind of start ruining Audrey and David's relationship, isn't it a little weird that David rejuvenates his relationship with his wife by keeping another secret. David pushes the paper across the table to Joseph, who is appropriately shocked. It's this amazing shot of Spencer Treat Clark completely flabbergasted. (Shyamalan will use this footage in the sequel.) But he's intentionally keeping this from Audrey. It's romantic in the sense that he knows that Audrey doesn't want David being involved with violence or danger in any way, shape, or form. But on the other side, David always feels unhappy because he's been keeping this secret about his potential quiet for his entire life. What is going to stop the story from progressing the same way that it did before? If David is meant to be a dynamic character, is he really changing? The movie really sells that David is this dynamic character. He goes from being a nobody to being a superhero. But David's central conflict isn't that he was powerless and now he's powerful. It's that he internalizes everything. He doesn't feel the need to express things that are bothering him. When Audrey asks him point blank to tell him if he's been with anyone, he clearly states the negative. But we know that, in the credit sequence on the train, that he hides his wedding ring when a pretty girl starts talking to him. He hits on her so much that she feels uncomfortable, and stresses that she's married. So while he's technically telling the truth, that he's not been with someone, it wasn't for a lack of trying. He keeps secrets with the assumption that the truth is going to break them. He even gaslights Joseph. The only reason that Joseph is in the circle of trust is because he was there when Elijah revealed his theory. Joseph needs his father to be special because he's kind of been a deadbeat his entire life. Making him a superhero gives that intense secrecy a reason for existing. I love the twist in this one, but I don't know if it was good for M. Night Shyamalan's career. When The Sixth Sense came out, everyone kept talking about the twist over and over. To follow that film with another movie that had a pretty great twist (but one not as strong as The Sixth Sense) made him the twist guy. I mean, I still make Shyamalan twist references. But I do have to question one of the moments in the twist. Glass makes Elijah full on Lex Luthor: Criminal Genius. But in this one, he feels simply part of the greater tapestry of discovery. But there's a moment where Elijah takes David's hand to wish him well. I 70 / 30 believe that he gives his hand on purpose. There's a need to reveal everything that he's done. He wants to be the bad guy for David. I don't quite know why he needs David to try to stop his evil deeds. (The text revealing what happened after is a pretty weak step on Shyamalan's point.) But there's this big question of "Why?" As the audience, it's extremely satisfying knowing that Elijah set up all of these disasters. But from a grounded perspective, why would he do that? Why make an enemy of David just because he can? It's such an odd point and I only have theories that stand up under squinting. But Unbreakable is an absolutely rad movie 20 years later. I loved Split. I'll talk about Glass tomorrow. But Unbreakable is genius not in spite it being boring, but because it is boring. That boring attitude allowed for character and setting to take the front seat instead of glitz and glamour. Also, I think Samuel L. Jackson is standing in front of a copy of Nick Fury: Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. towards the end, which is great. R for language and innuendo. At the core of Before Sunset is the idea that Jesse is tapdancing around having an affair. The movie doesn't really address the morality of this decision head-on. Instead, it focuses on the relationship between Jesse and Celine. The two also get lightly graphic about their sexual histories and choices, meaning that the vulgar language actually carries a vulgar connotation. It's pretty deserving of an R-rating, both for intended audience and for content.

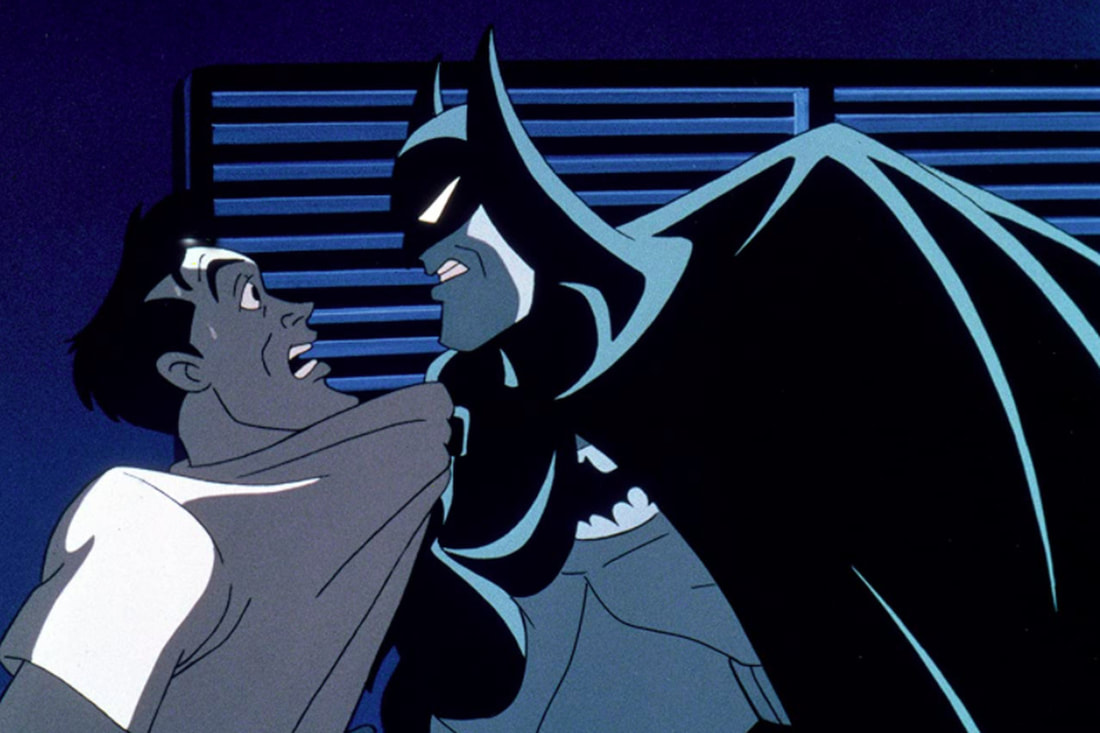

DIRECTOR: Richard Linklater I know that I'm going to watch the third one. I mean, I just know it. But there's something about the Before trilogy that both enthralls me and infuriates me at the same time. I have seen my fair share of Richard Linklater movies. If I had that time and the readership to justify making a "Directors" page, you could probably see that I have made my thoughts on Linklater pretty clear. There are times that I adore him and there's times that I roll my eyes at him. The Before series definitely reminds me of some of the stuff that annoy me about the director. Part of that comes from the fact that I simply have completely unreasonable expectations about the guy. I guess the annoying thing for me is that I kind of want him to sell out. That's a horrible thing to say, right? I mean, Linklater is famous and loved for a reason. But part of me thinks, completely unjustifiably, that movies like the Before series and some of his later independent feeling films, are easy for him to write. I'm going to try to redeem my thinking in a second, so please bear with me. The thing about independent film is that it is almost experimental by nature. The studio system does something one way and has developed a clear formula. But independent filmmakers do things another way. They break the mold when they make movies. The idea is that they have something new to say and they want to say it in their own fashion. Linklater totally does this. In my heart of hearts, I really like Linklater. But he also seems to be going to the same well time and again. If an experiment is to see if something works, he keeps running the same experiments over and over. Yes, Before Sunset is a commentary on time passing, both in the fictional world and in the real world. Ethan Hawke tends to like this kind of stuff, as evidenced by Boyhood. But looking at the Linklater ouevre, he keeps making movies about white people taking wittily. Very little of the story is plot driven. Instead, it almost seems to be this fly on the wall element to movie making. "Isn't it interesting how philosophical people can get when they think that no one is watching?" Before Sunset is an example of a fun date. The element that makes it a bit interesting ties into the title of the film. Because there is a deadline on the date, we realize that there has to be a change in the character before the end of the film. Instead of some grandiose gesture like we see in many rom-coms, the only requirement is that the protagonists either change or stay the same. But for all my criticisms that Linklater tends to stay in his little niche, I do enjoy these films. I mean, you have to be okay with boring. Both Jesse and Celine are likable and irritating as heck. I suppose that's Linklater's sweet spot for characters. Maybe they are all facets of him as artist and writer. But Before Sunset begs its audience to be a little bit evil while watching. From Celine's re-introduction, Jesse stands as a sympathetic character. The events of Before Sunrise defined Jesse. He was so moved and wrecked by Celine standing him up, that everything in his life revolved around the girl that got away. I don't know what kind of spouse would be excited to allow her spouse to write about the real love of his life, but that's simply something we have to accept. Because the moment we know that Jesse has a spouse and that he has technically (almost in a legal sense only) moved on, Jesse kind of becomes the bad guy. Our sympathies shift from Jesse to Celine. But even Celine is a deeply frustrating character. Celine chooses to encounter Jesse on this tour. Sure, Jesse laid out one of the most overt breadcrumb trails in cinema history, writing a novel about their romance. But Celine wants to seduce Jesse. Even when she finds out that he is married, she doesn't draw clear lines. (I'm still placing most of the onus on Jesse, considering it looks like he's actively trying to cheat on his wife with the girl that got away.) But the two intentionally, and completely unabashedly, wander into discussions about sex. They touch and flirt. This isn't even an attempt at closure. So when Celine grows irritated with Jesse in the car, there's a little bit of "What are you doing?" from the audience's perspective. Because the truth is that Celine is a very broken person. For as much as I gripe about Linklater returning to the same well repeatedly, he does really play the slow game when it comes to commentary on the problems with society's views on aging. In Before Sunset, Celine was meant to find the love of her life. That question of whether they'd see each other in Vienna six months later reflects Jesse's discussions with the reporters at the beginning of the story. If you are an optimist, then they lived happily ever after. If you are a pessimist, love doesn't really exist. But Linklater takes the road of the realist: sometimes things don't work out in real life as they do in movies. (I also read the irony of this sentence.) Sometimes grandparents die, or we get cold feet. But Celine is trying to be the girl she was in the '90s. She has responsibilities now. People have expectations of her to be married. And she keeps running into married men. I always thought the concepts of affairs was something that was only in popular culture, but apparently it's a thing. So Linklater absolutely nails the concept that people are defined by cultural norms and it is not fair. Jesse absolutely sucks for what he's doing throughout the movie. That ending, where he intentionally decides to miss his flight, is reflective of a person who feels entitled. He was supposed to meet Celine in Vienna and he felt abandoned. So his morality is now completely inappropriate. He is trying to recreate a past that never technically existed. Celine is okay with Jesse abandoning his wife and child. Remember, Jesse is not simply living for himself. One of the things about marriage is that there is no "just you" anymore. There are times where I wish I could have alone time. But I also know that my alone time means that someone is pulling double duty for me. Celine's frustration about being with married men is only compounded and Jesse is both the cause and the infection that follows. Is it a romantic movie? Yeah, I want to distance myself from that but I can't. It is wildly romantic. I need to know what happens in the third one. Is it probably going to be more of the same? Yeah. Linklater is more commenting on history progressing more than he is about specific relationship stuff. This movie is the product of being in 2004. While 9/11 isn't specifically mentioned, it does feel like Linklater is taking a photograph of the era for us to remember what conversations were like during this time. It's a bit dated sure and Hawke looks...rough (Sorry, Ethan Hawke). But it still is a romantic movie, even if it has this bummer context surrounding the film. PG, mainly because it is an animated movie. But the conceit of the movie is that there is a villain killing folks. This vigilante is acting like The Punisher and Batman needs to stop him. Okay, I don't know how PG that is. Add to the fact that there's straight up animated blood in this movie coupled with the Joker being hecka disturbing makes this a very questionable PG. It's part of the idea that animated films get passes that live action films don't. But I'm a bit of a hypocrite on this already. I also admit that Mask of the Phantasm is a good younger age Batman film before any of the live action entries. PG.

DIRECTORS: Eric Radomski and Bruce Timm There was a time in my life where I would testify to this film. Before you lose my meaning, Batman: Mask of the Phantasm is a fantastic Batman story. But I would be one of the hipsters who swore that Batman: Mask of the Phantasm was the quintessential Batman movie. Mind you, this is in the olden times, pre-Nolan Dark Knight trilogy. But there was a pride to really loving this movie. I always wondered, "Am I really a fan of this movie?" After all, Batman: The Animated Series was always quintessential Batman. But there has to be something special when a TV show makes the leap to film. The takeaway, as I've established, is that for a spin-off movie, it is pretty darned impressive. As much as my wife wasn't into watching this because it was an animated Batman movie, she didn't seem to hate it either. There was a sense of engagement. But the oddest negative thing I took away was how cheap this movie looks. It's not a pretty looking movie. I read a Buzzfeed article or something on this movie, and they talked about the genius art design. Really, Mask of the Phantasm looks only slightly better than a normal episode of Batman: The Animated Series. I'm pretty sure that I remember seeing this movie in the theater. Sure, back in the day, I might not have noticed that this movie lacked a certain polish that other movies would have. But my kids instantly pointed out some of the lower quality animation. The guests at Bruce Wayne's party are completely stationary. Also, this movie, despite being brought over to Netflix, never really had a high def remaster. I could have put my DVD into the player and probably gotten the exact same quality of film than what I showed the kids. It's so odd thinking that The Simpsons got a major animation upgrade but Batman got absolutely nothing. Because the movie is so short, I always thought that the film was a little underdeveloped. I don't know if that's true anymore. This really just felt like a tight, but short film. Because it focuses on a new character, it really did feel like reading something like Jeph Loeb and Jim Lee's Hush for the first time. The image of the Phantasm is a great and scary villain. It's a pretty smart move to have the Phantasm parallel the motivation of Batman. The motivation of the death of parents seems to be something that happens in comic books quite a bit. I feel a little bit like Elijah from Unbreakable (for good reason!) when I talk about comic book tropes, but the choice to make Phantasm a parallel for both Bruce Wayne and Batman is what really hits in this story. As much as I love Batman's code in these stories, the idea that he doesn't kill doesn't really make a ton of sense with his origin story. I suppose the idea that Thomas Wayne, as a doctor, would take the Hippocratic oath implies that he would do no harm. But Batman does plenty of harm. He just doesn't kill. And that's where the story gets interesting. What Batman: Mask of the Phantasm really nails is the stuff that isn't quite Batman. We care more about Bruce Wayne and Andrea than we do the character of Batman. Batman is seen as the burden that he is meant to be. I mean, the movie even ramps up that conflict by placing Batman in direct odds to the police, similar to the ending of Batman Begins. That might actually be an apt comparison. Because so much of this is Batman: Year One, it is interesting to see that some of the similar beats would be repeated again in Nolan's franchise. But I was always floored with the idea of the Gotham PD versus Batman. There's an episode of the newer Batman adventures (I forget the exact title of the later seasons of the show when there's a time jump and a change in artistic style), where Jim Gordon takes on Batman directly. We find out that the entire thing is a hypothetical situation due to Scarecrow's fear toxin, but that's when the show speaks most clearly. Batman is cool and all. He'll always be cool. As a Superman fan myself, I can't ever argue that Batman has the cool thing down. He's clever and agile. He does all kinds of martial arts tricks to take down the bad guys. But he's also the guy who has the least right to be out on the streets beating up bad guys. Yeah, the Gotham PD doesn't know that it isn't Batman killing all of the bad guys. They don't know about the Phantasm (although the assistant DA seems to have some insight into that). But it also is really revealing that Batman, with the violent beat-'em-up philosophies, is always just on the edge of what is acceptable. Because even though Gordon isn't on the squad, the rest of the police are aggressively opening fire on Batman. Remember, Batman isn't really fighting them. But the sour taste that Batman creates with the way he treats the law imbues him with the level of threat that the police see gunning him down as the only option. Part of it comes from the idea that Batman is talented. But is there a stipulation in the law that says if a criminal is really good at getting away, he should be open to lethal force? I actually don't know this answer. I'm sure a member of law enforcement could point that out. But remember, the GCPD went from having a Batsignal on the roof of Police Headquarters to full spread of weapons based on rumors. The fact that Phantasm is Andrea is a great shoe being dropped, but I don't know if it has the same staying power that the flashback sequences of Bruce and Andrea have. I mean, don't get me wrong. It might be the only way to really close up the movie. It was always so odd that, when reading Hush, people were wondering who was behind the Hush bandages. I mean, it was the only character who was being introduced in the series. Mask of the Phantasm has the same structure, again years before Batman: Hush. But I love the idea that the Batman persona is the element of the story that is most toxic to Bruce Wayne. We also read young Bruce as lost to the death of his parents. Batman was apparently born that day. But we see that there's an active moment where Bruce chooses to kill the Bruce Wayne identity and to become Batman. It's not something that was simply in him. The drive is there, but the obsession is almost cleared away when he puts on the mantle. I have to remember that Batman: The Animated Series is kind of / sort of a spinoff of the Tim Burton entries of Batman. The fact that the soundtrack to both sound so darned similar. I mean, Danny Elfman did both the film and the animated series, so it's not shocking. But Mask of the Phantasm really plays it a bit fast and loose with the Joker origin story. We don't get very much with that in this movie. But there's enough to contradict things that we're seeing in the comic books right now, especially "The Three Jokers" storyline. But since the Burton film acted as a very loose template for the show, and that film has a Joker origin, I can give it a pass. I will still say that Nolan's trilogy might be the ideal Batman films. But Batman: Mask of the Phantasm is a pretty great story, coupled with amazing visuals in a solid runtime. It's great to see when animation doesn't need to feel like a second class storytelling medium. Because the film focuses so much on the character of Bruce Wayne and Batman and not on the action elements, the film just really works. PG-13, but it does have some R-rated moments to it. It seems like it really floats around vulgarity at times. The language isn't anything to completely ignore. The movie centers around themes of adultery and alcoholism. Also, there's a scene that really glorifies the objectification of women, so it's not like there's a completely honorable disposition of the film. But it does kind of read like a really decent PG-13 movie. Just go in knowing that there's some questionable stuff. PG-13.

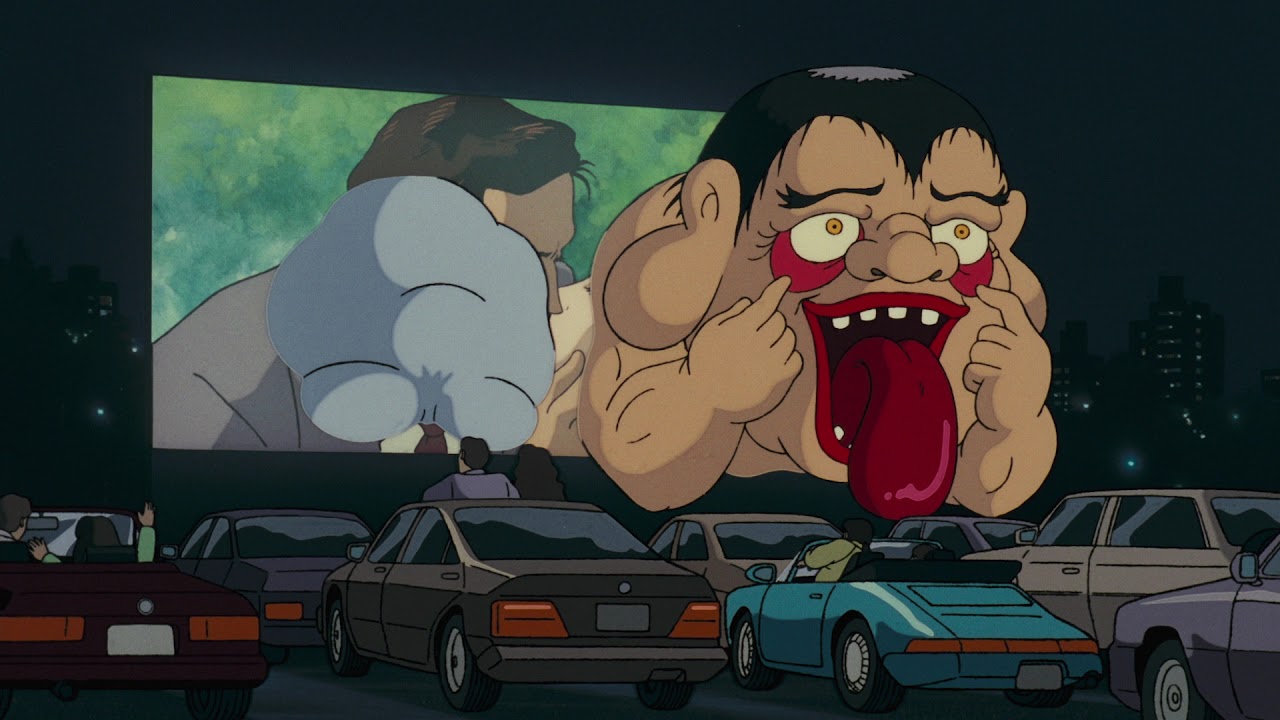

DIRECTORS: Jim Rash and Nat Faxon It's such a good movie and the disc came scratched. My wife's attitude is to just miss a section and rewind to where it is working again. There was a part of me that was grateful that we would have missed 20 minutes because we ended up getting another copy of the disc. Regardless, it does kind of throw a monkey-wrench in the ideal way to view a movie. I didn't really care though. Since having a billion kids, I've learned to watch movies any way I can. And with the case of The Way, Way Back, it was definitely worth my time. My wife and I have quietly and secretly become Jim Rash fans. Most of it comes from our rewatch of Community on Netflix. I know that he's an Academy Award winning writer for The Descendants, but in my mind he's still Dean Pelton. The Way, Way Back was way, way back in my queue, so it was a pleasant surprise to see when it came in the Netflix DVD sleeve. I think I've been pushing heavy movies for too long with my wife, so to watch a fun indie dramedy was exactly the mood we were going for. (Note: If you aren't in the mood for a fun indie dramedy, this probably isn't for you.) The Way, Way Back balances something that is very difficult to pull off properly. It is light and charming at times and sinisterly dark at others. A lot of props go to casting Sam Rockwell and Steve Carrell as opposite sides of the same coin. I will say that I never imagined that Steve Carrell could play this character in my mind. While he's played bad dudes, like his role in Foxcatcher, I never imagined him as the mean boyfriend character. While I'm not the biggest fan of Dan in Real Life, I've always pictured Carrell as that kind of male role model. He's the lovable dope who really tries doing the best thing. So when he's playing this role of Trent (which might be the perfect name for a jerk who is dating your mom), it's scary. He's really good in that role. The movie's opening, when he's asking Duncan to rate himself, is so telling of what that character will be is perfect. Carrell sells that character from moment one. Actually, before I go into Rockwell, I want to talk about why Trent works so well in this film. Trent is the bad guy. We're all meant to hate Trent from moment one because Duncan is our avatar. It doesn't matter that I'm 37, which seems to be ideal Trent age. We all sympathize with this kid because we don't want anyone dating our mom. ("Our mom" being "the universe's mom.") We are predisposed not to like him, which is normal. But Trent is a bad guy who doesn't see himself as the bad guy. He's a realistic jerk. He's the kind of jerk we all kind of know. He sees himself as a guy in a flawed situation. He thinks he's helping out the family with is tough love. This makes his attempts to bond all the more toxic because he's imbued himself with the role of the father before he really has any right to. Let's be clear: Trent is not a good person. But Trent is in a lose-lose situation. He knows that Duncan needs a father figure and, sometimes, being a father means being the bad guy. It's just that he actually is the bad guy. In the first half of the film, Joan attempts to seduce Trent. He does some B- fending her off. He doesn't quite reciprocate, but he doesn't get out of there as fast as he needs to either. But we see theses moments where he sees himself as the hero. He has this gorgeous woman throwing herself at him while his actual girlfriend kind of is a stick in the mud. It's this dynamic where two worlds are colliding and people can't force themselves to just make the entire situation work. Trent really sees himself as the victim of this whole thing. The joy of everyone in his house feels like it falls on his shoulders, and that's something that Carrell is playing fabulously. He is the bad guy, but he's a bad guy who keeps justifying his bad behavior because he feels put upon. Then there's Rockwell. Rockwell is great in so many things. Carrell's role is to be stone-faced serious. Trent is never hilarious, nor should be be. Owen, on the other hand, is completely hilarious. He's the relief and the father that Duncan and the audience bond with. It's so odd because, as an old fart, I know that Owen isn't a reality. Owen is the cool guy to the Nth degree. We all know that his life is a mess, but that never really affects him. He's Ferris Bueller all grown up and he's proud of that idea. It is a double-edged sword though. Owen is fun and he brightens up every scene that he's in, but also, I would never want an Owen in my life. Because the film is trying to swing the emotional pendulum both ways, we do have some painfully unrealistic and uncomfortable moments. It does really kind of feel like Owen is grooming Duncan. The Way, Way Back celebrates a more innocent time, when teens and adults can be friends. But it is really weird to watch Owen clamp onto Duncan. Duncan is quiet and reserved. Owen runs a water park. He sees all kinds of teens every day. What makes Duncan stand out? Have there been a million Duncans for Owen? I mean, what makes Duncan so special to this park? I get that he really works out once the film gets going, but those initial meetings come across as kind of gross. But all this being said, I was the teenager who hung out with Owens growing up, so my cynical blog can't really hold up to my flimsy anecdotal evidence. I think I probably was just watching as a nagging parent and I couldn't separate the concept. Moving on. The message of the selfish adult really hit home. There's so much in my life that is completely devoted to my family. I'm probably tired all of the time. I'm at a stage in my life that, if I decide to close my eyes and fall asleep, there are few places where that wouldn't have a follow-through. Heck, accidentally closing my eyes for more than ten seconds would probably lead me to completely take a trip to dreamland. My eyelids are getting heavy right now and I'm actively using my brain and sitting up in a well-lit room. So to watch a movie about parents who hold double standards for their kids is horrifying. Trent's warning to Duncan at the beginning, demanding that he leads a life outside the home, gets so much of a mixed message that it is dizzying. It's odd that everyone gives Duncan such a hard time considering that he's fulfilling the brief which has been given to him. But he's so afraid of his home life that he actually keeps a summer job secret. It's something that is his. Because he constantly is criticized, he can't actually risk sharing something so personal with the people who are meant to be closest to him. The Way, Way Back might be a criticism on our culture's view of aging. There's been a push back against adulthood with the assumption that adults know everything. But The Way, Way Back just have these immature adults that act like people do today. It's horrifying in a way. Do you know which couple I've rooted for harder than any fictional couple before? Sam Rockwell and Maya Rudolph. I had no idea. It was there and I loved the way that they played off of each other. There's something really cute about them together. I love how he worked to make the relationship into something, but lacked that certain extra step. While the movie is about Duncan and I never want to take the spotlight off of Duncan, Owen has his own journey. As much as Owen is a good influence on Duncan, Duncan is an equally good influence on Owen. There's this moment where Owen realizes his real age. He sees that Duncan is borderline abused at home and lives a life that he constantly wants to flee from. Owen's epiphany that he is the father figure that Duncan never had is satisfying. It's not saying that Owen has grown up in this moment. But he does realize that his goofballery has more value than bringing himself pleasure. I really dug this movie. I knew that I would probably like it, but it hit the spot I wanted it to. It's fun. It's funny without trying to be funny. It's serious without feeling too serious. It has this great vibe to the whole thing. It makes me want to rewatch The Descendants, which thankfully is in my Fox Searchlight box. PG, but it is a really weird and uncomfortable PG. Apparently, there's this element about raccoon mythology (you read that right) in Japan that involve raccoon testicles? That's a thing that is really lost in translation over her. So, like, a lot of the movie has very clear testicles on the drawings. The raccoons inflate these testicles to make blankets and fly around with them. Yeah, I'm uncomfortable writing this as much as you should be uncomfortable reading this. Similarly, male and female raccoons are distinctive because of breasts. If this wasn't uncomfortable enough, the raccoons try terrifying humans into leaving their land, so there are some disturbing images within the movie. But oddly enough, I kinda / sorta support the PG decision on this movie in the long run. My kids didn't pick up on a lot of the stuff that my wife were side-eyeing each other about. PG.

DIRECTOR: Isao Takahata So like when we watched Asterix the Gaul because my students were studying France, we decided to watch a Studio Ghibli film for Japan. Since we have watched all the ones that they wanted to watch in the past before, we decided to try this one. I don't know if I'm going too far on a limb to say that anime can get weird, especially by Western standards. Hiyao Miyazaki is a little off, but he is inspired by a lot of Western filmmaking. Pom Poko is next level weird. It never really gets into the absolute bananas stuff that I've seen with a lot of other anime. But I can't deny that this is an absolutely bizarre movie that I often have a hard time wrapping my head around. Part of that comes from the fact that the story of Pom Poko is entrenched in a lot of Japanese cultural norms that, as an American, I only have a little exposure to. For example, the testicle thing that I talk about in the MPAA rating. But I will never let my own cultural ignorance decide the value of a movie because I actually really liked it. I mean, I'm only occasionally grateful when my wife puts her nose to the iPhone, but she was giving some really good cultural background for the movie. And considering that our goal was to expose our kids to some deep Japanese culture, a lot of this really checks the boxes. This might be one of the greatest celebrations of Japanese folklore available to kids. (I mean, I do have to learn what it means when a fantasy character walks around with a leaf on his head because, between this and My Neighbor Totoro, it's clearly a thing that I should be understanding.) While Pom Poko is definitely a message movie, with its focus on environmentalism versus the onslaught of progress, it feels like it a mix between a character piece and something that is a fairy tale to those who know the story of raccoons. Again, as an American, I have to run to catch up on a lot of things. Things that I probably should have known before starting the movie is the rich cultural history of raccoons. The film stresses that people in Japan assume that raccoons are supernatural creatures that have the ability to shapeshift. That is not a thing over here. But I do like how this ability kind of defines their personalities. These aren't shapeshifting raccoons that often go for utilitarian choices with their decisions. Rather, there's something really telling about the forms that the raccoons decide to take. It's odd, especially, because the raccoons in this movie act almost as a hybrid protagonist. While we have Shokichi, the possibly more moral raccoon, he doesn't have a goal any different from the rest of his pack. Shokichi, instead, seems to be the character who is simply more developed than the other characters. He has a fate, and a depressing fate at that. You won't find me complaining very loudly when a story has a bittersweet, or even an outright sad ending. Shokichi, as a protagonist, is simply someone who we are meant to hold onto as our avatar. He's possibly the most human of the characters. He voices what the audience is thinking. He's one of the few characters in the story who have a named love interest. But even Shokichi isn't anything separate from his pack. While there are some that follow Gonta, voiced by a very Lex Luthor-y Clancy Brown, these raccoons all make decisions together. It's almost like we need Shokichi to remind us that there's a value in the individual. It's the concept that it is hard to empathize with a large group, but it becomes easier to relate to a smaller pack of animals. For a movie so entrenched in fantasy, it's weird that the movie is so darned serious about the ending of the story. Okay, it's not really weird. I completely respect that choice. Because it is a message movie, having elements of fantasy affect how the real world works is a bit of a cop out. The raccoons are losing their homes to industry and civilization. I like that the movie doesn't do what Avatar does and try to make the concept of progress this overt evil. Because people are moving in and need a place to live, they are wiping out the forest areas of the town. It's depressing, but it also makes a lot of sense. Considering that the majority of the movie is spent trying to find ways to get rid of the humans in the town, the grounded elements of us understands that they will fail. Civilization is an unstoppable force, for better or worse. (In this case, for definitely worse.) We are an invasive species. It's this brutal story to tell to children. It's not like we see a ton of death. Some of the raccoons die by getting hit by cars. It's bleak, but it also isn't overt. Instead, we're left with the flaws of a utopian vision of harmony. The raccoons, as a last reminder of their supernatural abilities, show the world of apartments surrounded by nature. We know that this isn't ever going to be a reality, but it is this nice dream of man and nature living symbiotically instead of parasitically. There's also a weird meta narrative to the whole thing. So, my favorite scene is the part where the raccoons all shapeshift into people without faces and torture the poor policeman. Oh my goodness. Good stuff. I'm surprised that my kids didn't freak out forever over that. (For all I know, they did and this is all being repressed.) But the real piece de resistance is the parade in the middle of town. The goal of the raccoons is to put on an absolute nightmare of a parade. They have all been practicing to up their games. They have gotten the shapeshifting masters to help them learn what needs to be done to ensure success. Cool. All of this is rad. And they put on the most insane spectacle. The best part is, while some do honestly become frightened, the general consensus is that this is the best parade that is imaginable. Instead of fleeing for their lives, they're all mesmerized by this spectacle. Eventually, to provide further commentary, a local huckster takes credit for the spectacle, which is pretty damning of human beings in general. But what a commentary that makes about the fascination with horror. Pom Poko is all about scaring humanity out of complacency. But we're watching the movie to see how horrifying these raccoons can get. Once the film is over, there's a good chance that we'll continue living in our comfortable homes. I know that my house a hundred years ago wasn't the suburbs. As much as I'd like to think that I'm the hero of the story because I sympathize with the raccoons who are losing their homes, I'm really still the villain. Like the spectators of the parade, I'm there to see the spectacle, think about it, and move on. Pom Poko is pretty great. I don't have any kind of authority to say if Pom Poko gets the respect it deserves. I know that it is in the Ghibli lineup, but I feel like it doesn't get the attention that the Miyazaki ones do. A lot of that comes from the idea that Westerners probably can't wrap their heads around the overt weirdness of the movie. But really, it should be watched. Most environmental message films tend to be a bit...trash? But Pom Poko really hits a lot of sweet spots, despite the abundance of raccoon testicles. Approved. A Raisin in the Sun is a heavy one. While not littered with traditional bad language, the film does feature heavy racial and homophobic language. The protagonist is thoroughly unlikable and the film has the specter of abortion hanging over the film as a whole. Walter is also a serious drinker and does terrible things while he is drinking. It's an important movie, and important stories often have controversial content. Approved.