|

Rated R and Marvel is super proud of that. While the f-bombs are akin to what we've seen with other Deadpool movies, Deadpool & Wolverine just amps up how much violence and gore there is. I mean, the other ones are violent. This one is priding itself on the gore going through the roof. There are sex and drug references all through the film, but this movie is tamer in terms of sex and drugs. The movie is trying to offend on a certain level, so keep all of that in mind when taking children to see the newest R-rated MCU film.

DIRECTOR: Shawn Levy Be forewarned! I'm not the biggest Deadpool fan in the world. Things that I think are true: 1) Ryan Reynolds is very funny and a perfect Deadpool. 2) These movies are fun and incredibly watchable. 3) Ultimately, these movies are fine. Like, I get it. The jokes are funny. But the whole meta thing sometimes gets to be a bit much. I absolutely think that these movies should exist and I always have a pretty good time at these movies, but I'm never going to be part of the Deadpool Parade. So keep all of that in mind when I'm not absolutely in love with Deadpool & Wolverine. I remember a time when there were three MCU movies in the theater at the same time. A lot has changed since then. Disney has limited MCU films to apparently one per year. The crazy part is that the only MCU movie we're getting in 2024 is an R-rated MCU movie that I can't take my kids to. Sure, we got a couple of TV shows. Heck, we got Loki season 2, and that's some of the best stuff that the MCU has made. (By the way, for all of the cameos in this movie, how is Owen Wilson not in this film?) As the only MCU movie this year, there's a lot on this movie's shoulders. Part of it comes from the idea that I want the meta-narrative to be pushed forward. Now, I'm in the minority (which has been confirmed by Deadpool & Wolverine itself) that actually really likes the Multiverse Saga. I think Marvel, for the most part, has kept up its tradition of excellence. But on top of needing to continue the entire Marvel Cinematic Universe, Deadpool & Wolverine is also the movie that is responsible for bringing Hugh Jackman out of Wolverine retirement for a movie that should, by all intents and purposes, be the ultimate Wolverine movie. There's a lot on this movie's shoulders. While that responsibility falls on Ryan Reynolds, Hugh Jackman, and Kevin Feige, I don't know if it lived up to that expectation. This movie got sold hard. Like, really hard. Like, it was going to be some top tier Marvel according to them. I will say, it does exactly what it should, but it should not have been lauded as this great return to greatness for Marvel. Really, Deadpool & Wolverine is a great Deadpool movie and an even better Wolverine movie, but it isn't objectively one of those movies that is going to change things. We've been waiting for mutants. Mutants still kind of only exist in another timeline. We've been waiting for Deadpool and Wolverine to join the main canon. That still isn't true. Instead, we have this as a finale to a different universe that has nothing to do with main MCU canon. As a fond farewell to the 20th Century Fox movies, this movie absolutely slaps. It's such a lovely goodbye to an effort that pulled off a proto-MCU before Marvel Studios formalized what is considered the Sacred Timeline. I don't think anyone would deny that first and foremost, this movie is a roast of what came before it. Deadpool movies are silly. They're meant to be silly. But these are jokes told with love. After all, Feige cut his teeth on these movies. He learned what it meant to make quality superhero movies. And, sure, the 20th Century Fox Marvel movies have probably been more miss than hit. But these were movies that were made with an intention to bring quality storytelling to the big screen. As much as we kind of giggle in Deadpool & Wolverine, I was genuinely happy to see some of the characters that showed up from non-MCU films. Honestly, there's a top-tier movie in here if you really trimmed it down. When the movie takes itself with a modicum of seriousness, there's a pretty solid film. A lot of that comes from MVP Hugh Jackman, who hasn't lost a step as Wolverine. Sweet mercy, I was ready to give him a little bit of a pass when it came to this character. Sure, he's done it a million times before. But I've been watching the press circuit with goofy, giggly Hugh Jackman, seemingly giddy to be hanging out with Ryan Reynolds, and I forgot that the guy knew how to give old knifehands so much pathos. Honestly, the dude delivers on every single beat that he's in. He never breaks character. I know that we had an R-Rated Wolverine in Logan before, but somehow he never got lost in the campiness that is a Deadpool movie. Part of me was going to be disappointed that this wasn't the Wolverine from the X-Men movies. I don't know why that bothered me. Maybe because I invested so much into that character that seeing someone who had the same actor, but a different story seemed disingenuous. But honestly, Jackman made me really like this Wolverine. He's a little bit of a "What If...", but I didn't mind that at all. The movie works with what we have with this character. I cannot stress this enough: Hugh Jackman as Wolverine in this movie fit like a glove. He seemed like a young man doing it all over again. But that leaves me with the rest of the movie. I can't stress this enough. This movie is incredibly funny. It absolutely nails what Deadpool is all about. But if a Deadpool movie is a balancing act between diagetic storytelling and meta jokes, this movie might be going too far into the meta world of the MCU. We all get it. Deadpool is aware of the world of comic books. He's aware that he's in a movie. That's fun. But this was some inside baseball stuff that went a little too far. There were a lot of moments where I could feel myself being totally insufferable and explaining a lot of the jokes to my wife. Having to explain Blade: Trinity jokes was almost a step too far. That's kind of the problem with Deadpool though. Deadpool desperately wants to do both. He wants to be a satire of the comic book movie character while simultaneously being the quintessential comic book movie character. I don't know if Deadpool really grew in the ways that I wanted him to go with this movie. Considering that this was the movie that everyone seems to really like, I found myself a little tired of this deep dive into the cinematic history of Marvel movies. But again, it's all well and good. There's a very good chance that I'll end up owning this movie on Blu-ray. I'll watch it a few times. I'll have a good time each time I watch it. Seriously, it's that fun. But in terms of actual comic book storytelling, I got really bored with the Void. The Void was slightly tiring on the few episodes of Loki that we got. Having a big budget tentpole movie take place almost entirely in the Void seemed like a bridge too far. The MCU really hadn't advanced that much because of this film. It kind of felt like another inconsequential side story, despite the fact that it opened the doors to a lot of potential superheroes showing up in a potential future Avengers film. I wanted a "Can you believe that they changed everything?" and really ended up with "I suppose that you could use these elements later on." It's good, not great. Hugh Jackman? Great. The movie as a whole? Fun, but okay.

0 Comments

Not rated, but this movie involves the murder of a little girl. Also, there's a weird sexual sequence involving blood that I really can't explain. Yeah, this movie should be R-rated, but also has the tone of confusion, which makes it seem somehow more scandalous. Honestly, if I could beat-for-beat explain what was going on in this movie, it wouldn't be that bad. Most of the movie is the protagonist walking around, delaying revenge. Oh, and the death of Yan is pretty intense. There's some animal cruelty in the film as well.

DIRECTOR: Yermek Shinarbayev Oh man, there are so many things that I want to do way before writing about Revenge. This is another entry in the Martin Scorsese World Cinema Collection from Criterion. I think Revenge exactly nails what most of these movies feel like. My gut reaction is so disrespectful that it isn't even a little bit fair. Part of what I honestly feel is that I'll probably forget every single movie in this collection. Scorsese's right. These movies need to be shown to the world. Just because we haven't heard about these movies doesn't mean that they don't add to the cinematic canon. But there's also something about these movies that almost feels like homework. Revenge kind of nails that vibe perfectly. One of the coolest things about Revenge is that it is a fairly modern movie that looks gorgeous. Most of the things that Americans associate with Kazakhstan is what we get from Borat. It's kind of why the joke works so well in those movies: we have no idea what Kazakhstan is actually like. In my mind, it is mindblowing that Kazakhstan, Korea, and Russia aren't that separated. I'm going to admit that I'm not used to Asian cultures speaking Russian throughout the movie, let alone the fact that Shinarbayev was trained at the VGIK. Ultimately, the thing I like about Soviet era cinema is the very specific tone that is nailed in these movies. I'm always kind of impressed by how they manage to get an epic scope with a bleak tone throughout. That sounds like I'm dogging the film. I'm not. But I did say that this did feel like homework and that often comes from the fact that the movie dances between experimental film and traditional narrative. From a traditional narrative perspective, a lot of Revenge works. I don't know what it is about the chapter format when it comes to movies, but I like digestible stories that lead to a larger whole. Mostly this works. But there are parts that are either completely abstract and unproven or just a mess. The film wants to get to the point of whether or not the young protagonist, Sungu, should actively pursue a revenge that fundamentally isn't his. That's a really nifty story. All of the stuff with Sungu is the stuff that makes you think and question morality. A good revenge story should do that, by the way. It's critical of the one getting revenge. But this is a story that really spends a lot of emotional and philosophic real estate trying to get us to question Sungu. So the middle of the movie, while sometimes abstract, is well-developed. Getting there and getting out of the movie are weirdly raw and make not a lot of sense. The film starts out with Yan, a teacher, just murdering a little girl. The class is lightly giggling at his attempts at classroom management. He then resorts to slaughtering this little girl who did nothing wrong. Now, that's pretty weak. But as a character, we're meant to believe that he didn't want to kill this girl. He was pushed too far on the wrong day. (All off my complaints about this movie are silly and superfluous. I know this story isn't about the narrative. I'm just complaining because these moments irked me.) Okay, it's weak, but I can live with that narrative. I invest in that moment. But in Book Three or something, Yan visits Sungu. He's there to brag. What is his entire intention for doing this? I know that Tsai failed to kill Yan when he had the chance, but it seems really out of character for him to intentionally hunt down the elder Tsai and remind him that Yan killed his daughter and there's nothing that he can do about it. The crux of the film is that Sungu would have made a great poet. He was this kind boy who was literally bred for revenge. He never knew his sister (although even that is kind of betrayed later in the movie when he sees the ghost / hallucination of his sister outside of Yan's home). The frustrating thing is that Tsai gave up, something that also didn't make a lot of sense to me. Tsai pauses when it comes to killing Yan because the healer distracted him. But he kind of just...stops? The married couple comes up with this idea to impregnate a mute concubine and that Sungu should be the vessel for revenge? It's all...odd. I get the notion. We wanted to have a naturally good person searching for a revenge that wasn't his. But also...how did we get there? There are all of these moments that are a bit of a bridge too far. The insane thing about this is that the parts that are good are actually great. Much of the movie is just this exploration of a life abandoned. Again, that is a movie I can get behind. The worst part of me complaining? That's most of the movie. Most of the movie is about Sungu, taking a right when he should have turned left. It's not even about this kid who is fully devoted to murdering Yan. It's not that he avoids his destiny. It's just that he's in this holding pattern for the majority of the movie. Instead of being a poet and living with his mother, he works in a saw mill and lives a hard life. He could have bee-lined it for Yan. I suppose a lot of that comes from the fact that he lives in a pre-Internet society and he's not trained to be the World's Greatest Detective. But a lot of that is just the notion that the Sungu that was meant to be cannot exist. Even when he wants to find comfort in sexuality, there's the image of the bleeding genitals. It's a weird moment guys and I'm unpacking it as I write. While this moment is meant to tell that Sungu is suffering from the same ailment that killed his father, I get the idea he's just not allowed to have a moment of happiness. It reflects the curse that his father placed upon him: no joy or sorrow. The thing is...he feels a lot of sorrow. The entire movie? Sorrow. It's a terrible life. He's just this guy who floats his way through life because he's living someone else's life. Now, I thought that this was going to be a movie outright commenting on the folly of revenge. I don't think the movie gives me that kind of satisfaction. Through Sungu's tarrying to kill Yan, Yan lives a far worse life than you could imagine. The coolest part of this movie is that Yan spends his entire life looking over his shoulder, expecting retribution for the murder he created (coupled with a weird boasting that just made things worse). He leads a terrible life as an alcoholic that is bullied by school children. (Also, these school children confirm my theory that children in foreign films are real psychos and make American children in movies look like saints.) A flaming rat (yup) catches the barn he's sleeping in on fire and he burns to death, alone and drunk. It's a lot. That's a cool ending. The weird part is...that's where the story of revenge should end. Then...Sungu gets revenge even though Yan's burning to death seems like it's a way better revenge than sickle murder. The woman that helps him, the healer, with whom he bonds, is somehow killed by a truck towing some absurd piece of metal? Then he cuts that lady's head off using the sickle. What? Why? That's not an ending. That has little to do with the story. At best (AT BEST!), I can see it in the sense that she was married to Yan and the closest thing to killing Yan would be killing the wife that hated him? Or maybe because she interrupted Tsai's initial attempt to kill Yan? Either way, kind of a messy ending and I'm going to go as far as to say that it was there for shock value. I don't know. I told you. The beginning and the end of the movie are a mess. I do still think that it is unfair that I'm poo pooing this movie as hard as I am. It's just that, as good as the good parts are, so many moments are a mess. The funny thing is, the next movie on the same Blu-ray is pulling the same card. For as many pretty moments are in the film, there are some that are sloppy and rough to watch. I wish that I was really sold on these movies as being classics. But they do feel like homework. I guess I'm glad I watched them, but they are a bit of a burden. PG-13 for some mild language, racial themes, hate speech shown in a negative light, and mild sexuality. Honestly, the sirens scene might be the only thing that slowed me down from showing this to my kids. The racial stuff, it's done in the context of saying that Americans are racist, especially in this time period with the Klan. The Klan look like jerks. I can get aboard the Klan looking like a bunch of jerks. Oh, and there's some animal cruelty and death in the movie.

DIRECTORS: Ethan and Joel Coen Do you know what is incredibly dumb on my part? It's a little after 1:00 am. I just finished posting my Twister blog moments ago, but I wanted to close up my "to do" list before going to bed. So I thought that I would have a late night / early morning cup of tea and knock out O Brother, Where Art Thou? and hoping that I'll find what I want to say as I write it. There are a couple of blasphemous confessions that I'll have to make early on. The first is that, even though I'm an English teacher, I'm pretty sure that I never read The Odyssey. There's a chance. On my Goodreads account, I apparently gave The Iliad a one-star review way back in the day. This sound like me, by the way. It makes absolutely no sense, but Greek mythology does almost absolutely nothing for me. To apologize for this gap in my education, I started slowly reading it on my Kindle, reading annotations as I go so I can really grasp this. The second confession is that, the first time that I saw O Brother, it did almost nothing for me. That has changed. I'd like to put that out there right now. O Brother, Where Art Thou might be one of those perfect films and it is straight up a crime that I didn't care for it the first time. I have always criticized Young Me's tastes. When O Brother, Where Art Thou? came out, I think one of my favorite movies was Moulin Rouge. (One day, I'll have to write a blog about that movie and I think I'm going to be ashamed for a long time.) Part of my dislike for O Brother stemmed from the fact that I thought that it was going to be a very different film than it was. "Man of Constant Sorrow" was the entire trailer for me. I heard that song everywhere. For some reason, I thought that the movie was going to center around that song when I first saw it. That song is in the movie twice and it kind of is not about the song. If anything, this is a somewhat silly look at character and setting and that's what makes it absolutely great. Do I wish I knew what The Odyssey was like besides a general idea? Yes. That might be the only thing that can make an already great movie already better. But even if I took O Brother as an original work, the concept is kind of brilliant. The "Escaped Convict" movie is kind of a win-win for any storyteller. Ultimately, it has the best genetics from the road movie, but it also gives a sense of stakes and impermance that is necessary to make a road movie great. The trio in this film, as silly as they behave, ultimately have to be emotionally up and down constantly throughout the movie. Part of this comes from the idea that Johnny Law is always on their tails, but it also comes from personalities that might not match the depths of their characters. Clooney's Everett is a bit of a mislead from moment one. For the lion's share of the movie, Everett comes across as a con man. He's even got the hair treatment to go with the Slick Willy persona that he outwardly manifests. It's heavily implied that he's an armored truck thief, but we discover that Everett's crime is far more noble. He's accused of practicing law without a license. The Coens aren't dummies. While they never harp on this point and never give him a free pass, Everett's crime is one of technical altruism. We never really get details on Everett's slightly illegal law practices, but my natural inclination is that he tried to do right by someone and got caught doing it the wrong way. Honestly, Chaotic Good alignment and all that. Contrasted with Everett is Pete. No one in this cabal is truly evil. After all, Pete was supposed to be getting out of jail in two weeks if it wasn't for this mythical reward that Everett spun. But Pete is potentially the most criminal out of the three. He's not a bad man. But he lives in a world where crime is almost part of the moral fabric of day-to-day life. He has a sense of right and wrong and the law is not a motivating factor in those decisions. I adore that Pete is mad at Everett for stealing his cousin's watch, despite the fact that his cousin reported them to the police. And, as silly as it is, he kind of has a point. Everett does all of these immoral acts before they end up being justified by someone else's actions. Yet, he doesn't mind all the crime that is happening around him. Delmar is the comic relief. He's a lovable moron. But O Brother, Where Art Thou? is just a playground. Yes, we deal with morality and friendships that develop through the story. I honestly want to talk about God a bit in this movie, but I have to put the playground first. One of the things about the road picture is that every story is a bit of a fish-out-of-water story. These three, in their pursuit for a treasure that doesn't exist, run into every scenario that is meant to test comfort zones. But what makes the movie such a joy to watch is something that the Coens and Wes Anderson share in terms of attitudes. These characters find the absurd to be mundane. That's where the comedy really hits. I'm thinking of a handful of other road movies. These road movies are great, so I'm not trying to disparage them. I'm just saying what makes the Coens and Wes Anderson so great. If you look at National Lampoon's Vacation, Clark Griswold is continually flummoxed by his bad fortune throughout the story. That's normal. As much as Clark is an over-the-top character with some abhorrent character traits, he's meant to be our avatar for the movie. The trio here act in the most absurd ways imaginable. They meet George "Babyface" Nelson (but don't call him that!) on the run from the police. When he tells them to get into the car to help him with directions, despite seeing the approaching police on the horizon, they don't even question Nelson's request. When Nelson robs a bank, they find the whole thing a bit much, but that never really slows them down. They're eager to help their new friend, even though he seems almost psychotic in his desire for infamy. And that's the film. Clark Griswold probably would have robbed the bank as well, but the comedy there would have been him trying to get out of the situation. Instead, the Coens painted their protagonists as guys who are going to see every situation through until the end, no matter how silly. A Bible salesman beats Delmar silly, Everett is going to see where this is headed. That's the movie. And that's perfect. This ties into some of the message of the film. The movie has two contrasts between Everett's grounded nihilism in the form of vocal atheism and Delmar and Pete's newfound religion. Delmar's innocence is so intense that it becomes contagious for Pete. Delmar, the second he sees a chance to save his soul, bee-lines it to the front of the line to get baptized. Pete watches, more confused than skeptical, and sees the man get submerged. Delmar, in all his simple-minded stupidity, explains that his sins were forgiven and that he's no longer guilty. That absurd notion is enough for Pete and that colors the rest of the film. Everett becomes our avatar then, understanding as we do that it doesn't quite work that way. But the story is partially about how Everett isn't really part of the gang until the end. Throughout the film, Pete is questioning Everett's de facto leadership. It's because he's not really one of them until he gets down and prays. If anything, this is a case for God, which is fascinating. It's not like Everett will ever truly abandon his atheist spin, despite evidence to the alternative. Instead, he becomes almost more respectful for the boys' joy in their faith. He's the one who ends up looking a little silly when he sees the oracle's prophecy come to fruition in the river. It's almost as if Everett and God make a little deal to treat each other with a little bit more respect and that's enough. But as much as I can wax poetic about themes that make the movie work, this is just Joel and Ethan Coen doing what they do best. The aesthetics of a Coen Brothers movie is so specific that I've never really seen anyone nail it exactly the way that they do. The Coens have an appreciation for a specific shade of Americana that takes a very specific personality to really enjoy. And the thing about that look at Bluegrass attitude comes with it a slightly teasing tone. I almost said "mocking", but I don't really think that it is it. These guys keep making movies with these cultural touchstones because they are almost immersed in these kinds of characters. They can poke fun at the things that they love and there's really nothing wrong with that. It's teasing someone in a best man speech, not a roast. O Brother, Where Art Thou? is a masterpiece. I'm ashamed that I didn't really give it the time of day when it came out. But between the Coens being on the ball with their comedy coupled with a visual and audio aesthetic that can't be beat, this might be one of those few perfect films. PG-13 for language, including a hidden f-bomb if you have the subtitles on. I think the subtitle even pops more if you have a room full of nieces and nephews with your kids watching it on a big screen. The movie is a disaster movie, which means you are going to have some scary moments involving death, destruction, and blood. But besides the random language and a radio tower to a guy's face, the movie is more tame than I remember. PG-13.

DIRECTOR: Jan de Bont Yeah! We watched Twister, just like everyone else in America. It's right there, sitting on Max. Nobody's stopping you. Crank that nonsense on. We watched in the garage at night with the garage door open. It was a beautiful night, which felt like a lost opportunity because this movie would have slapped even harder in a thunderstorm. It's been a minute since I watched this one. I honestly have more memory of the Universal Studios experience than I actually do that movie, so it was fun coming back to it. I'll be honest. As much as I'm a fan of a silent film watching experience, I just had to talk all the way through this movie. And I'll tell you what. In this case --IN THIS SPECIFIC CASE --it made the movie better. Twister is its own thing. Okay, it's not. But Twister is both an absolutely terrible forgettable movie and a pretty darned good movie at the same time. Like, it's a dumb movie. It's almost absurd what goes into this movie. It's a bunch of dumb, but lovable characters, doing incredibly dumb stuff over and over again. I get it...partially. From Jo's perspective, she's doing this for a cause. She wants to stop what happened to her as a child from happening to anyone else. But also, like, what? There's a lot of times where I wonder what the grand plan was. Okay, I'm just going to go into my major gripe for the movie that I kept shouting out. Dorothy, the weather system that Bill (Bill Paxton plays a character with whom he shares a name), needs some time to set up. Sometimes. SOMETIMES. The entire plan: Move this Dorothy unit in front of a tornado and then get out quickly. Yet, they really dawdle on setting up Dorothy. (The reason I stressed the "sometimes" bit is that the climax of the movie, Jo just flips a switch and it's good to go.) (Also, UPDATE! It's way too late, yet I am deciding to stay up and knock out two potential blogs? That's stupid, but I'm doing this because my summer is practically over.) So much of the movie is them getting close to a storm, then getting wrecked by that storm because they drove into a storm. The crazy part is that the conflict of the movie is almost entirely arbitrary. Again, this is a dumb fun movie. The first draft of this movie had to be "We're driving towards that storm." "Nope, not the right storm." To fix this, they added scientist bad guys (whom I want to discuss ad nauseum besides the fact that the entire plot device is hilariously dumb) and non-flying sensors. I'm going to talk about the sensors first because I'm locked into them, but we're going to do our best to turn this around on the scientist bad guys. The sensors in this movie often get wrecked before they have a chance to get them airborne. Okay. Honestly, a lot of that comes down to lack of prep time because the container that the sensors are in gets knocked over all of the time. The movie doesn't really make clear whether or not the Dorothy container is important to the sensors working. In some ways, it's kind of like that "Is the Kool-Aid man the glass or the liquid?" meme, only with a Macguffin. So in one of the rewrites, someone said that the sensors had to be somehow the problem with driving into storms. So they called up the Pepsi corporation and asked if they wanted to be the reason that people stopped dying in tornados. I'm not the biggest fan of product placement. I was going to try and defend myself by pretending that product placement never really bothered me, but between the box of Cheerios in Superman: The Movie and the fact that I can't give Cast Away a reasonable chance, I think I'm pretty anti-product placement. When Bill said that they need to find as many aluminum cans right now, I called shannigans because there's clearly no recycling plant in a town that just got leveled by a tornado. But even more insane is that every single one of them was a Pepsi product? Come on. Sure, there's a version of the story where Dustin goes into a convenience store and buys out every case of Pepsi, downs a handful and spills a whole bunch into a ditch. Sure. But I don't by that. That doesn't ring true. Instead, what does ring true is that Warner Brothers got some quick funding from the New Generation to pup Pepsi all over these little sensors. This bugs me. Evil Scientists. I told you they bugged me. I'll tell you why. When I was a kid and I saw Twister, this raised no red flags. After all, Cary Elwes was born to play the sleazy competition in a movie where you kind of have to shut your brain off. I even get that it is immoral to steal Bill's tech and try to deploy it yourself. But do you know what doesn't really match this story? Rushing to see whose tech can get into a tornado first. Let's imagine that this story went a little bit differently. After all, Bill didn't know that the F5 for sure was going to drift into Jonas's car. He suspected that it might have, but he wasn't sure. And let's say that Jonas got his sensors up into the air before Bill did, despite the fact that Pepsi wasn't sponsoring Jonas's cube drones (which had to fly worse, right?). Jo's entire internal conflict was about the fact that she needed to pursue the weather to make sure that no other kid had to go through what she went through. (Oh, I need to talk about Meg's mandate to Jo before I close up!) If Jonas's thing worked, it would have soured a good thing. But let's remember. It still would have been a good thing. The goal was to get information on how tornados worked. If these storm chasers could have figured out how tornados worked, then people would have been saved. Yet, a lot of this movie is them almost killing each other trying to get to the tornados first. Seems kind of morally weird and such an odd choice for an antagonist for a film. I don't know if I have enough meat on this bone to provide a weighty argument worthy of a blog. Meg, Jo's aunt, gives Jo a command. After Meg is almost killed in her house, Jo says that she's going to stay with Meg until she gets better. Meg, aghast as such a prospect, gives her a real Jonathan Kent speech, saying that Jo has a responsibility to stop the F5 that's heading for more of Oklahoma. I think all of our brains made the leap to "What she meant was that Jo has to finish the job so, in the distant future, tornados could be detected quicker and easier." What she actually said was something along the lines of "Stopping the tornado." That's not the plot of this movie. Jo, nor anybody else, really has that kind of power. Stopping the tornado was never on the docket, Aunt Meg. But it is one of those rally cries that gets everyone on board. After all, if Meg, who has just lost everything, tell you to pick yourself up, you gone done pick yourself up. I think this might be a '90s thing, but I forgot how much of a romance this was. It's got some heavy rom-com vibes and formulae to it. Add Dr. Melissa Reeves to the pile of jilted significant others who really didn't deserve what they had coming to them. Dr. Reeves was there to be supportive. Yeah, she's a little confrontational. She's a therapist. Okay, she's a reproductive therapist, but she's at least trying to start a dialogue with Jo when things get awkward. Like Jo, she knows to get ahead of the storm so it doesn't take you by surprise. She does almost nothing wrong, but Bill kind of mentally cheats on her. Okay, give him points for not actually cheating on her and hooking up with Jo until after Melissa dumps him. The only actual crime that Melissa did was being too cool with Bill about the entire events of the day. She really could have vocalized that this behavior was inappropriate early on and that's a bit on her. But she also had some reasonable expectations that Bill would have considered her needs over that of the group. Still, rom com vibes. As much as I'm teasing this movie, it still kind of slaps. (Oh yeah, the CG is hilariously bad and I fully blame 1996.) This movie is worth it almost entirely for the drive-in movie sequence. Yeah, I teased it by saying that you can't make a movie better by showing a better movie in the middle of it, but that scene genuinely is incredibly memorable. But that doesn't mean that the entire movie wasn't dumb. I read somewhere that Jan de Bont was caught off guard by the announcement of Twisters because he wasn't consulted. In my head, I started equating Twister to this cinematic masterpiece that couldn't be touched. I now get why they didn't contact him. There really was no need to. This was a movie that hit right and does a lot of the disaster stuff right, but ultimately is a fluff piece that capitalized on the Amblin vibes that we don't really see anymore. Is it perfect? Far from it. Instead, it's just a really good movie to watch in an outdoor theater, as long as you have good speakers. Not rated, but almost as innocent as a movie can get. There's one thing in the movie that could cause someone to look away. One of the recurring images is that the subjects of the documentary are watching a magic show. One of the magic tricks / gags is that the magician puts a knife through his arm, causing it to bleed. But he even warns you that it is not for the squeamish, coupled with the fact that this is clearly a trick. Besides that, nothing I can think of.

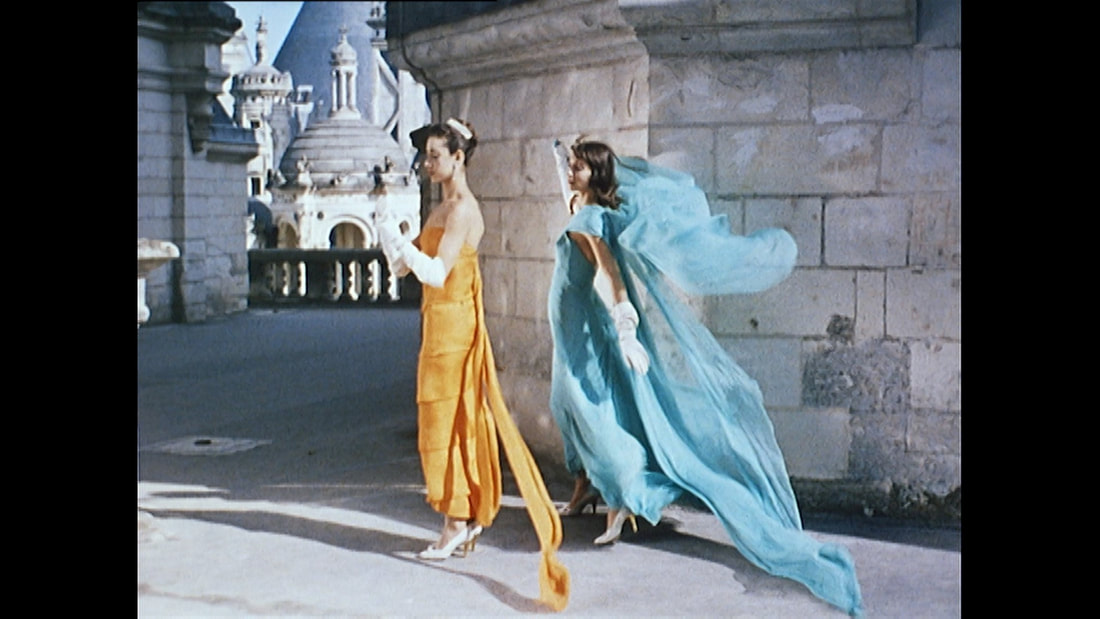

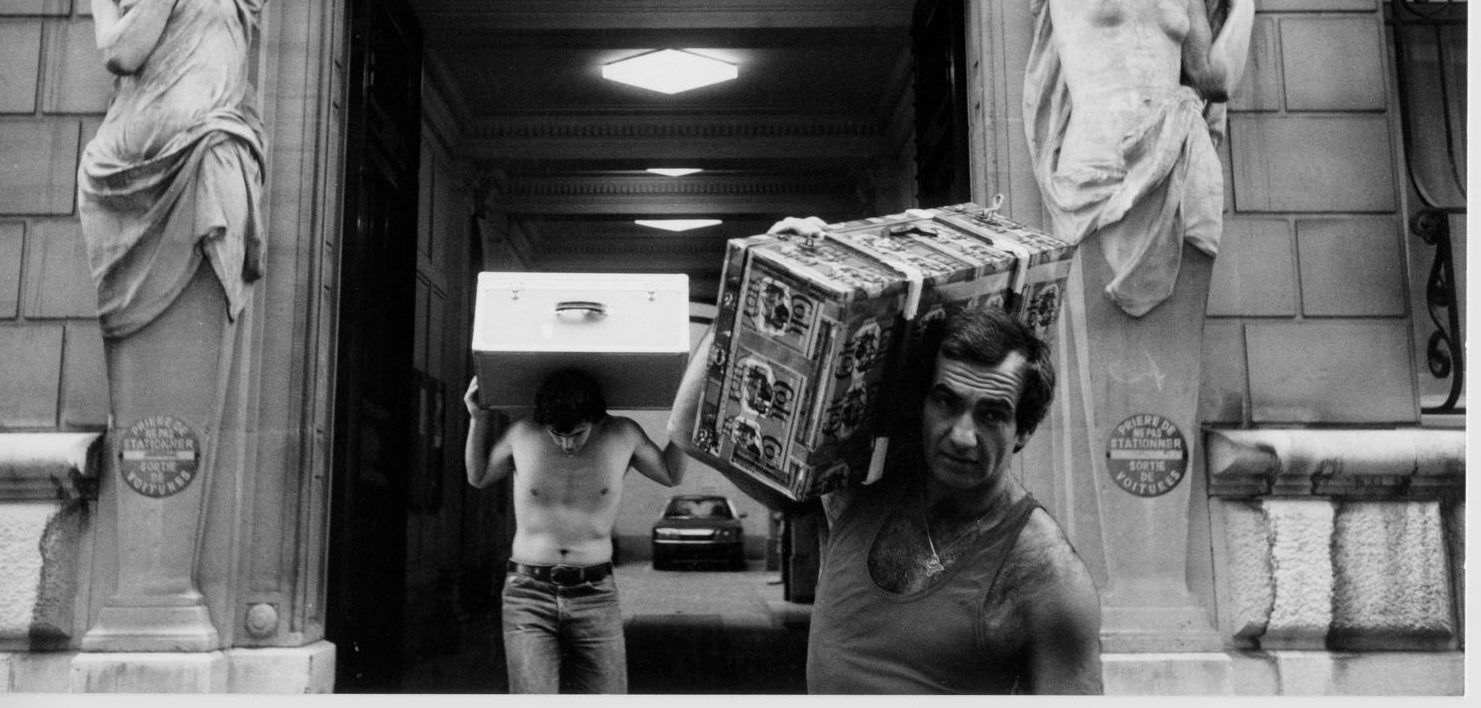

DIRECTOR: Agnes Varda I've been trying to find the time to write this all morning. Hazel is having another "Hold me, I'm a baby" day. I might have a few minutes to knock out a couple of sentences, but we'll see. Her nap is in the next twenty minutes and I might get ten to do something with this. I'm in the weird place, blog-wise, where I have too many massive Blu-Ray collections and I'm trying to do all of them. That's a great place to be, by the way. I'd rather be in this pickle than the alternative and having to scrounge the bottom of the barrel looking for movies. But with all of these box sets, I realize that it's been kind of a minute since I've really broken down an Agnes Varda movie. I think it will always be true that I'll prefer a traditional fictional narrative from Varda than watching her documentary work. But I also have to say that I'm more familiar with her later documentaries than I am her earlier documentaries. Daguerreotypes might actually hit a sweet spot with me because this is Varda at her most pure. Varda is someone who just loves having a camera. When she overthinks things, I feel like it comes out like an imitation of Varda rather than something truly authentic. Again, the gall on me to even question one of the greatest filmmakers of all time. But Daguerreotypes feels incredibly authentic. Varda (I think it's Varda!) narrates the movie sparingly, which I really appreciate. But in that narration, she's almost diary style, discussing why she's making this movie. She loves this street. She loves the vendors who live on her street, so she made a documentary showing what it must be like to live in their shoes for about an hour. Using mostly cinema verite methods (with Varda's obsession will mildly scripting moments), we kind of get an understanding of why Varda is so moved by the people who surround her geographically. There's a bunch of clever things she does in this movie. Remember how I just told you that she gets out of her head in this one. I kind of still stand by that idea, but I feel like some of the real genius moments in this documentary probably happened in post. I can't deny that the introduction of a magician had to be somewhere in the planning stages for the movie. But also, the takeaways from the magician sequences had to be just a moment of joy for Varda to find with her direction. The magician, in this movie, does a bunch of stuff for the film. One of Varda's themes in the film is the necessity for both practical manual labor and the joy that art brings. The movie has a lot of themes. That was one of them. Don't fight me on this. But she does so by having the working class people watch this magician. I've mentioned this sentence ago. I'll try to keep up too. (Note: There was a break there where I had to put the baby down for a nap and then the day got away from me. I told you this would happen.) It's this moment that me as the audience sees these folks having a good time, but ultimately looking at this buffoon put on an illusion act. It's in these moments that we have to have people who want to have a good time. Thank goodness that's the way that the room went, but it almost didn't have to. Watching these people have incredibly repetitive lives that is backbreaking, how can they contend with the notion that someone is going to sell them on fantasy? And that's where Varda really sells me. She has been microdosing me a theme for the majority of the movie. I watch these people who are happy enough, but doing the same thing on repeat and she straight up asks these folks if they dream. Some of the business owners respond very literally, talking about the process of sleep and repetitive dreams that they may have. The clock owner, appropriately enough, talks about repairing dreams and that the same dream --pun intended! --comes to him like clockwork. But there are others who get the double-meaning of dream. While few people feel outright oppressed by their chosen professions, they still think about the path not taken. It's a little heartbreaking, if only because we're all dealing with a variation of that. Varda herself has a modicum of celebrity by this point in her career. Heck, I could mention the name "Agnes Varda" to a room full of people that I regularly talk with and I'd probably be the only person not only knows about her, but has a strong opinion about her work. But Varda kind of becomes the distant observer who is part of the story. One of the things about Varda is that she's one of these directors who embraces her humanity through her work. She's always in a state of self-discovery. That self-discovery comes with a little bit of a character that she puts on, but she's woven into this narrative. Her asking these people if they dream is both a moment of common bonding and also, subconsciously, an affirmation of her own choices. She is the one who is always doing what she wants to do, regardless of what is expected of her. There is little repetition in her life because she's always pursuing the next thing. As much as I criticize her later work, it's probably healthy that not all of her movies slap. That means that she's not just doing the thing that she knows works. Can we talk about the sub-documentary in this movie? I'm talking about the perfumery owners. There's a joy to all of the subjects of the documentary. They're so happy to have a little bit of spotlight on their small lives that they're smiling and desperately not trying to look at the camera, with the exception of the talking heads portions. But the perfumery owners? He's an incredibly old man who is happy to be there and seemingly loves his wife and his wife? She has some degree of dementia. She looks so sad and so lost and of course she exists in that space all the live long day. It's a place that has existed longer than the other places. It relies on almost no outside commercial involvement. The bottles of perfume are found bottles with handwritten labels and this poor woman just seems like one of forgotten bottles that they sell. It's incredibly emotional and Varda seems so sympathetic towards this woman. Good! We all have souls. Listen. I'm not sure why I like this movie. I kind of spelled it out, but I admit that another day, I might have hated it. While it will never be one of my favorite Varda films, it's incredibly peaceful and --even more importantly --incredibly personal. I love myself some vulnerability and this movie is vulnerable. I'm changing things up. I have The Complete Films of Agnes Varda box set. At first, I thought that this meant only the feature length films. Nope. This includes the short films as well. Since I'm painfully a completionist, I'm watching all of these short films as well. But I also know that I can't write an essay about each and every one of these movies. So instead, I'll do some blurbs about each one as I watch them. So I'll keep updating as I go along. Les 3 boutons (2015) -I think I like Varda's early work a lot. I've talked about this in Varda by Agnes and Visages / Villages. It just seems like it was trying less to be art and simply was art back in the day. Again, I don't mean to poo-poo. Varda has more artistic merit in her pinky than I'll ever have. To a certain extent, this movie felt like some of her earlier work. It had a narrative. It had a confusing narrative, but it was a narrative. But in the mix of visuals, I kind of lost the point of it besides looking pretty and being artsy. Ô saisons, ô châteaux (1958) -There is something incredibly satisfying about this. There's an innocence to Varda as she's making what ultimately is a comissioned travel film. She seems worried about upsetting those who are hiring her while trying to maintain an artistic integrity and it is near perfect. Yeah, it's a travel promo film. It's the equivalent of a town asking for an extended infomercial. But it works so well. But not as well as... Du côté de la côte (1958) -...this. In the same year, she's hired for basically the same job with the French Riviera. Then she just goes bananas and makes her own art film that happens to be emotionally about the French Riviera. When the folks who hired her saw that she claimed that the best view is from the grave, were they all excited about it? This is Varda that I adore. She's spunky and adorable and has social commentary, even when she's hired for travel videos. L'opera-mouffe (1958) -I'm living with a very pregnant lady right now. She doesn't go around the streets of Paris making little art films. This one is pretty. Maybe things in black-and-white get a little bit of a pass compared to things in color. I'm not normally a fan of strictly experimental cinema, but this mostly works for me. Maybe because it is so hypnotic and relaxing that one can't help and view the movie through the lens of calm. It's sad at times. I lost myself in my own mortality watching this one today. There was this old woman who looked so rough and the camera just stayed on her for longer than was appropriate. I then realized that this lady, along with almost everyone involved in this movie, was probably dead. But that old lady also has this specific form of immortality because film snobs like me will watch everything that Agnes Varda has ever made. Les dites cariatides (1984) -Varda still has it going on in 1984. I think it is when film goes digital is when I get off the Varda train. I think she picks her shots so beautifully when film costs money that, when it is disposable, she doesn't quite get that same sense of grandeur. She has a specific subgenre of experimental art film. It's almost a documentary, but with little done in terms of informing. Varda shows all of these women carved into stone and tells the story of the inspiration of these pieces. But the point of the documentary is not to have you leave and tell your friends about what you learned, but to experience the same sense of awe that Varda does while looking at these moments. The 2005 update doesn't really deserve its own section. That's just someone's slideshow of statues. But it shows what can happen when a filmmaker really pays attention to the small stuff. T'as de beaux escaliers, tu sais (1986) -I almost didn't write about this. I'm actually kind of amazed that I found an image of this. It actually is probably from another movie. It's funny. Varda says that this isn't an advertisement; it's a documentary. It's both. It's an excuse to say that Varda really likes film and I have no problem with that. It's what I really like and to claim that this is my favorite of Varda's shorts is a bit too much fan service. Doesn't mean that I don't like it. Le lion volatil (2003) -Man, Agnes Varda --especially older Agnes Varda --was a sassy old lady. In the introduction to this piece, she spills all the tea about how her producer disappeared with all of the money that was meant to make this short into a feature length film. I'm already starting to see some of the weaknesses of Varda in 2003. She wants this to be this heady piece about love around this neighborhood, but it all feels a bit forced compared to the other stuff we've seen. It's cute and I like the fact that it has a narrative. But it also wears 2003 really hard.

Rated R for a lot of language, some nudity, and its fair share of violence. This is a subgenre of film that almost doesn't exist anymore. It's the fact that the movie knows that it's getting an R rating, but doesn't mind being lighthearted the entire time. Despite the fact that this is a movie about drugs and murder, the film's tone is a lighthearted romp. Still, you can't deny that the movie has questionable content. The movie really plays it fast-and-loose with homosexual stereotypes. It never gay bashes, but there are moments that seem a little regressive. I'll say that it has enough questionable content that I was glad that I didn't invite my in-laws for this movie on the big screen. R.

DIRECTOR: Martin Brest This will probably be one of those disjointed blog entries. I have a baby demanding to be held every second today. The second that she discovers that I'm trying to be mildly productive, she's going to demand that I walk her around the house and play with her. It's a lot today, so I'm really hoping that I have some time to knock this blog out. I'm kind of amazed that everyone hasn't seen this movie. Beverly Hills Cop is almost a second tier classic. It's one of those movies that so many people have seen and could possibly quote, but it might be one of those movies that's vanishing from the cultural zeitgeist. I mean, it's not shocking why I'm rewatching Beverly Hills Cop. The new one on Netflix just came out and it's been a minute since I watched this. The funny thing is, in high school, I probably watched this movie about half a dozen times and the only parts that I really remember were the banana in the tailpipe scene and Serge. It's amazing to think that Eddie Murphy is only 22 in this movie. He was on Saturday Night Live at the age of 19 and he's headlining major franchises when he just learned how to drive. He doesn't feel 22, by the way. Something made people age in the '80s. I'm sure some of you are finishing the sentence with "It's drugs". You know what? I don't know what was going on. I just know that Eddie Murphy doesn't feel like a 22-year-old in this movie. When he's lauded as one of the best detectives in Detroit, there's a heavy implication that he's been doing this job for some time. So much so, because he schools Taggart about tricks that drug smugglers use that should be common knowledge for an old fart like Taggart. Still, this is prime Eddie Murphy. Eddie Murphy might be having a bit of a renaissance now because he had fallen off the grid for a while with a string of rough films. But since he came out with Dolemite is my Name, it seems like he's had a return to form with some of the recent releases he's had. (I hate everything that I just wrote, but this baby is going to demand attention sooner or later.) It's kind of hard to criticize Beverly Hills Cop or to look at it objectively. Beverly Hills Cop is in that '80s action-comedy genre that probably shares some DNA with Lethal Weapon and its ilk. These are movies that have the cinematic grandeur of a big blockbuster action movie, but with the narrative of something that could almost be improved on the spot. Really, the meat of these movies is the clever dialogue, the over-the-top scenarios that the protagonist has to overcome, and --ultimately --fun characterization. These movies live or die on the charisma of the protagonists and Axel Foley is incredibly likable. Like with Lethal Weapon, Axel is fundamentally down on his luck. He's a guy who is so good at his job, but is surrounded by incompetents who are stymied by a respect for tradition. Now, this should be a major red flag for me. After all, if Axel Foleys existed in real life, I'd probably be marching against people's civil rights being trampled upon in the name of justice. But these movies make guys like Axel so darned charismatic that we just ignore due process. That's really the lesson of the film, by the way. Police procedure and doing things by the book are only in place to protect bad guys. Lying and ignoring the justice system is the only way to get things done. It's told through two juxtaposed environments. With Detroit, there's shortcuts. Ultimately, though, these shortcuts are done for comfort's sake. No one really cares about justice. They just don't want to annoy the higher ups. Beverly Hills, however, is this bastion of morality. So much money is thrown at this department that there is an expectation that crime would be non-existent in an environment that everything is done right. By accident, by the way, this is a movie about privilege. No one really expects the dirty old Detroit to be getting the job done properly. (There is some racial coding going on here as well.) They just don't have the resources, thus there are lowered expectations. But Beverly Hills finds law enforcement so easy because they've always had resources. (Again, racial coding going on here.) It's weird. During my heavily conservative high school life (of which I wish I could rewind), I found myself watching Lethal Weapon a lot more. I know that Murtaugh dealt with racial tension, especially in Lethal Weapon 2, where he fought against apartheid. But that racial commentary seemed so unifying and safe. Racism came from South Africa, thus it wasn't an American commentary. To a better extent, Beverly Hills Cop is a little more critical of American law enforcement. I'm not giving it any awards. Let me be clear about that. This is a pro-law enforcement movie that actually encourages cop to take laws into their own hands. But Axel, as his characterization dictates, is always going to say what is on his mind. He drops the n-bomb, accusing these White people of treating him as a second class citizen. But the most telling is one of the funnier moments in the movie. Axel Foley is thrown out of a window by the bad guy. In that moment, he's arrested for disturbing the peace. Now, there's an actual law being broken by Axel that is never addressed. He should have been arrested for trespassing. Okay, but he's arrested for disturbing the peace. From an initial observation, Axel looks to have been assaulted by having been thrown through a window. But these rich White police officers see him and blame him for the event. (Yeah, it kind of is his fault, but that would take a while to deduce for anyone else.) That entire rant? Pretty great and obviously haunting considering racial tensions with law enforcement. I gotta give Beverly Hills Cop the edge over Lethal Weapon. It's funny to think that this movie is about Axel Foley, a Detroit police detective, only being involved in this case because his criminal buddy (who changed the course of Axel's life) divulged information about current criminal activity. It seems like that shouldn't have been Mikey's opening line, showing all of these stolen German bearer bonds. But you know what? The story couldn't have moved forward. I read somewhere recently that Murphy didn't care for Beverly Hills Cop III because Axel didn't have skin in the game. I kind of like that Axel doesn't care that Mikey was a criminal and that he angered his employers. It makes the movie kind of a bit more dynamic, knowing that Axel can get his hands dirty from time-to-time. I don't have a ton of analysis beyond what is here. This is one of those movies that wears its heart on its sleeves. While there is some racial commentary and economic commentary, it's all done out of a sense of fluff. It doesn't make the movie bad. It does make the movie fun. But I don't want to diminish the fact that it could make a fun piece of entertainment that isn't devoid of politics. Instead, it weaves it into the narrative. Could Beverly Hills Cop been more critical of law enforcement? Absolutely. Was that on the shoulders of 22-year-old Eddie Murphy in an era that might not be ready to hear that message quite clearly? Not really. It's a good movie that is a little more vapid than it should be. But that's how these things work. Not trated, but a main character faces a pretty gnarley death with black-and-white blood all over his face. Also, there's a weirdly unaddressed age and consent issue with someone who is considered a family member (if only by marriage.) Bergman once again seems to normalize the concept of domestic abuse, implying that men sometimes absolutely just need to put a woman in her place. But still, not rated.

DIRECTOR: Ingmar Bergman I'm going to forget that I watched this movie. It won't even take that long. Maybe --just maybe! --I'll remember that I've seen it but couldn't tell you a darned thing about it. Part of it comes from the fact that the title is reminiscent of an Ozu title. But Summer Interlude, while not being a bad movie in itself, feels potentially the most underbaked of the Bergman movies that I watched so far. It's a real bummer because, despite the fact that it is once again incredibly bleak, this might be the most traditionally romantic movie that I've seen come from Bergman. There's the heavy implication that Henrik doesn't come out of the movie intact. We know that from moment one. After all, Marie seems upset with her life. Her relationship with David, while somewhat charming at first, seems vapid and empty. (I'm going to maintain that these two don't actually have a working relationship, despite the fact that the movie ends with them together and in a healthier place.) This is the story of a summer romance. I enjoy the fact that it has the name "Interlude" in there, tying back to the notion that Bergman is once again analyzing the role of the artist with the art. I can see why Criterion bunches these movies together. While not potentially thematically tied, there are motifs that drift between films. (I'm actually going to break my own rule with the next Bergman I'm going to watch and jump on ahead to the television version of Fanny and Alexander, simply because I want to create a little bit of a distance between watching the television version and the theatrical version.) But Bergman almost uses the dancer as a means to somehow relate to the female character. I realize I'm being incredibly unfair, but I'm starting to pull Bergman down from his pedestal. It's not Bergman that I have issues with. The issue that I'm coming to grips with is that Bergman is not just one person. In my mind, Bergman was always The Seventh Seal Bergman or Persona Bergman. Bergman never really gets dumb, but he also is a dude who might not always have layers and layers to his planning with his characters. With To Joy, he had his male protagonist be the artist. It's not unreasonable to make the leap that Bergman is using that violinist as an avatar for himself. He's the artist who has the frustrations between what it is like to be the grounded person and the person aspiring for greatness. The next year, he comes out with Summer Interlude and again puts an artist in the role of the protagonist. I applaud the fact that he stretches his wings, challenging himself with the notion of a woman artist instead of a male artist as the protagonist. But I also see the shorthand. While it isn't art that drives Henrik away (directly) in the film, there are moments where it causes strain on the relationship. The very character of the artist is almost a conflict to the plot itself and it makes sense. But Bergman's argument between this and To Joy is that artists are completely capable of having healthy relationships. It just involves putting the self aside. But that's not the point of this story, is it? As much as a good 70% of this movie is devoted to the summer of Marie's 15-year-old self (something I absolutely need to address later), the movie isn't strictly a traditional romance between Henrik and Marie. Bergman weaves in conflicts to keep the middle part interesting. It's probably why Uncle Erland is so darned gross. If Bergman is going to tell a story, he's going to lace it with conflict just so that there can be something to watch. Ultimately, from Marie's perspective, her relationship with Henrik is untouchable. It was the happiest summer of her life, but that's really boring to film and probably even more boring to watch. That artist stuff? It's a distraction from what is actually the theme of the story. Really, we're supposed to be paying attention to the other 30% of the story: Marie doesn't know how to grieve. I said that this movie might be Bergman's most romantic tale and I still stand by that. But the meat and potatoes of this film are about how it is important to properly feel sadness and to confront the past. Really, the movie is just Inside Out. Erland isn't the healthiest human being. In fact, I think he's one of the more screwed up characters out there. There are times when he ranges from all out gross to just being a sad old man. But he's one of those gross characters who means well (and you should absolutely not forgive him for hitting on his 15-year-old niece). But he's trying to protect her. He knows that she's going to go through unfathomable pain, having lost the first love of her life, and he wants to protect her. Unfortunately, it's one of those things where there is no right answer. Again, as romantic as this movie is, it's really about dealing with trauma. But I do need to talk about some weird choices. I don't know if this is reflective of Bergman, his Swedish background, or a hodgepodge of both, but why does he intentionally make things so messy? I've talked about it with the rest of the movies that I've watched in the box set so far (I have so many left!). People treat each other terribly in this movie. The first real issue that I have and that I've alluded to is the fact that the movie makes Marie 15. From a certain perspective, I see why setting it 13 years before the adult Marie is in the film. Part of that comes from the notion that this has to be a first love. Secondly, Marie has become so overwhelmed with adulthood that her love for dance has somehow devolved into a burden. But when the movie makes her fifteen, there's the real issue of what Uncle Erland's attraction to her is. Part of it is the fact that he was attracted to her mother and that he can't divorce the two images from themselves. Okay, but that's not what the movie is about. But the other part is that, as much as we like Henrik, he's not appropriate for her. The movie implies Henrik takes her virginity and that's just a concept that is in the movie. This is also coupled with the idea that Marie is emotionally more mature than Henrik. I know. I know. I'm retreading ground with Bergman's need to create conflict. But Marie and Henrik are terrible for one another. Marie is absolutely awful to Henrik, like many other of Bergman's romance stories. She flirts with her uncle. She calls him a baby for being emotionally invested in many things, including the awkward family life that he deals with when it comes to his lodging. But the crazy part is that Henrik is also kind of the worst? He's handsome, sure. He made the first move, sure. But the rest of the characterization of Henrik is a man-child. He's this guy who actually tells Marie that he's borderline unlikable. He has no friends. No one cares about him except for his dog. But he's also one to go cry in the bushes the second anything bad happens to him. For all of the goofy moments between the two of them, Henrik exacerbates things the second that things don't go his way. Yet, Marie keeps oddly repenting for her behavior despite the fact that Henrik can't deal with conflict in a mature way. The movie is good. I don't dislike the movie at all. It's just that I will not remember this movie. It happens. I was scrolling past the Film Index section of this blog and there are a lot of movies that I feel like I've never heard of, despite writing long-winded essays about all of them. Still, it's worth a watch. Not rated, but this is a movie that, while not being completely explicit with some of these things, deals with some absolute misery. This movie deals with alcoholism, abortion, infidelity, potential murder, and domestic abuse. Also, it doesn't really condemn the spousal abuse as much as it should. It's one of those "forgivable offenses" in this movie. Considering that this is a love story, it's pretty much a bummer all the way through. Again, not explicit in a lot of cases. But they talk about it and the physical abuse doesn't show the victim through the beating. It's still rough though.

DIRECTOR: Ingmar Bergman The War of the Hobbies against Time rages on. The baby is asleep for a nap while my wife texts me with questions. I know if I don't write this blog right now, I won't be able to get to it until late Sunday night. I have sixty plus pages to read in my book today and I'd love to do a million other things. The house is also a mess, despite the fact that my daughter swore that she wouldn't make a mess if I allowed her to make cookies. I have about an hour to all of these things. Admittedly, I lead a blessed life. ...unlike these folks. (The one thing I'm great at? Transitions!) I'm pretty sure that I've seen this movie. Not only had I seen it, but I'm pretty sure that I put it on my recommendations shelf one week when I worked at the video store. I think I just wanted to come across as hoity toity by putting a lesser known Berman film on my recommendations shelf for the week. But when I put it on my shelf, I was a sad single man who liked bleak things. I had no idea what marriage was all about. It was all videos and hobbies all the time. (Oh man, the sheer amount of hobbies I would have destroyed in this time was admirable!) This is a movie about marriage for married people. Bergman probably gets as close as he does to a morality play with To Joy, although now I really have to question Ingmar Berman's morals. Bergman has always been pretty upsetting when it comes to relationships, romantic or otherwise. His movies tend to show awful people being awful to each other and it's always just a bit too depressing for me. To Joy might be the biggest bummer from me (from the oversized Criterion set) so far because To Joy tonally might be his most romantic film. Just to give you context for how bleak this movie gets, the film starts off with one of the protagonists being informed that his wife blew up and that his little girl is badly burned. You'd think that the rest of the film would be a flashback explaining how they had a perfect marriage. No, they had a trash marriage. For some reason, we get this absolute Mary Sue of a character with Marta, a character who is the ideal wife. She is cooler than Stig, her husband, and never cheats on him. (Do you see where I'm going with this? Stig cheats on his wife. There. I cleared things up.) And then we have Stig, who sucks from moment one. Now, part of the story is that Stig's journey kind of parallels Scrooge. He's a jerk and she's going to make him a better man. This is where Bergman kind of gets me angry. Stig may be one of the most unlikable men ever. We're meant to dislike Scrooge when we meet him, but the journey both softens him and gives us context for his behavior. Just to throw myself under the bus a little, Stig and I share a very specific trait. I'd like to think that I temper this attitude more than Stig does, but I'm not distant enough from myself to firmly make this claim. This could be why I get so angry at Stig now. Stig has that fear of mediocrity. He's an artist who always imagined that he would have free reign to pursue artistic excellence and that he would receive affirmation for this impressive accomplishments. In of itself, that's not too toxic. It's just that he views any kind of obstacle to his rise to success as something to be quashed. Honestly, that kind of makes Marta the antagonist of the story. Marta throughout the film is completely sympathetic. She's an antagonist in the sense that she is in the way from Stig's obsession with artistic freedom. But she's the hero of the piece, without a doubt. Stig is the monster. Again, I do hate Stig way more than Scrooge. The reason why I hate Stig is that Stig, while being a character who makes a dynamic character change in the final act, isn't a character who makes a choice so much as he hits rock bottom. There's no one else to hurt, so thus he comes to the realization that he has to be a better husband. That's not romantic. If anything, that's kind of pathetic. I talked about this in the content section, but he straight up beats his wife because she commented on his poorly hidden affair. She wasn't even yelling. And this is where Bergman kind of loses me with this movie. He beats his wife and it's meant to be a low point in their relationship. Bergman's message in this movie is that marriages can be rough, but we should cherish every moment because it could be gone just like that. But Marta absolutely should not stay with Stig. I don't care that she has two kids. We would have forgiven her if she left after Stig left to have an affair with a terrible human being. But he straight up beats her. Again, this moment is supposed to be a character low, but Stig learns the wrong lesson from this. This might be a dated and cultural thing, but I'm not letting it off the hook. There's a part in the climax, when the two decide to fix their marriage, that Stig is thinking of all the mistakes that he made that led them to this moment. He says that he finds the beating to be something that needed to happen to make him love her all the more. I'm wording it poorly, but not as poorly as you think. That's pretty gross. I don't care for that at all. There's a story in here that I really like. I like the idea that To Joy shows the concept of marriage, warts and all. I like the idea for, all the growth that happens within a marriage, it is because of growing pains and obstinancy. But this movie gets to be too much. Bergman's attempt was to show how low a marriage could get before being redeemed. But it, by accident, almost excuses the behavior that the characters go through because it shows that anything can be forgiven. I can imagine the same amount of frustration without any of the abuse or infidelity. Most fights that my wife and I have are about dumb stuff. Things that I hold close to me tend to be death by a thousand papercuts kind of things, not massive drag-out-beat-up things like To Joy is showing. That's the message I want to see. I want to see the story of how much better love is than the moments of sadness that hit all of the time. It's the knowledge that, as low as a daily grind can get, moments of joy overshadow all of that stuff. Instead, we get Stig the Monster who absolutely needs to be in prison and alone. Then the movie ends with the knowledge that Marta --sweet and kind Marta! --is going to die from a kerosene stove exploding? Also, good for Stig for going back to work to be this strong man for his kids. But remember how one of the kids is badly burned and almost died? Maybe that kid should get a little bit of attention. To throw this blog into the gender studies camp, it's also odd that it was the girl who was horribly burned by the kerosene stove. The low hanging fruit is something that Bergman straight up put in his dialogue, that the woman enjoys cooking for a husband. But the bigger question is what Bergman might be subconsciously saying about the role of men in society. These two come out of this tragedy with an emotional burden that can be lived with. But we don't even care about how the female character has been horribly disfigured and witnessed the death of her mother? It's an afterthought because the male child watched his father play well. I don't know how good of a message that really is. My reptile brain does like the movie overall for multiple reasons. Besides being well-paced with some great interactions and slices of life, I think I like movies about musicians. It's another movie about artists and there's something incredibly satisfying to see creative obsession. Also, the fact that they are classical musicians means that the moovie is scored with epic classical music. It works really well for me. There are moments that remind me of Whiplash. Am I supposed to hear how terribly they are playing or is that part of the whole bit, that the director will never be happy with perfection? I don't know. All I know is that aesthetically it is cool. I kind of wonder what I saw in this besides outright cynicism, despite being a romantic drama. It's watchable, for sure. But it also has some really weird messaging going on. Rated R for a lot of language. Like, the amount of swearing feels like a 20-something wrote this to shock the system. It just so happens that the movie is good, so we forgive the childish amount of swearing. There's also a blurry shot of a rape and the amount of violence in the movie is pretty upsetting. The Usual Suspects, from a parent perspective, is one of those movies that really tries to be shocking. Depending on your level of densensitization, it's really not that shocking. But if I listed the sheer amount of lightly R-rated things, you'd be impressed. R.

DIRECTOR: Bryan Singer Kevin Spacey in a Bryan Singer film. How different were both of their lives in 1995? I always kind of treated The Usual Suspects as one of those bro-ey college movies that White men absolutely adore. It kind of is that movie, by the way. I never necessarily feel great watching this movie. But it's also a really good movie at the same time. My film class alumni came together and watched this one and it is one of those movies that really does need to be watched at one point or another. Honestly, there was probably a time that lauded this movie as the best thing ever. But this might be another one of those movies that is kind of ruined by the fanbase as opposed to the actual quality of the film itself. I think I have to write a formal SPOILER warning in this one. I am spoilery about everything I write, but The Usual Suspects really gets elevated by a twist ending. I remember watching this back in the day and being blown away by the twist ending. It's still a pretty good one. But showing this to viewers today, I had two former students just shout out almost simultaneously, fifteen minutes before the reveal, that Verbal Kint was Keyser Soze. It's a disappointing feeling, that oment. One of the greatest moments in film is when the filmmakers catch us off-guard. I don't know if viewers are becoming more savvy, or is it that so many people have taken the template of The Usual Suspects and made their own movies involving flavors of the same twist. It may be a combination of both. Maybe one of the great things about the '90s (which is making me sound incredibly Millennial right now) is that we kind of had a return to form to the Hitchcock style reveal. There were some absolute bangers of films that nailed a big final act reveal. The problem is that we kept trying to ride that train and now we've kind of formulized original concepts. It's weird to talk about Kevin Spacey now. I had to Google what the status on Kevin Spacey actually is right now. Spacey was acquitted of charges of rape and I hear that he has a movie lined up right now. Okay. But there's a lot of people that say that he groped them and I don't love that. Okay. I have to look at this movie as a movie and Spacey as Verbal as a performance. It's so integral to the film that it needs to be broken down. I'm going to preface this by saying that Verbal isn't my favorite Spacey performance. Before all of this stuff came out, I was a huge Spacey fan. I almost watched The Big Kahuna, despite the fact that it looked terrible, because I knew that Spacey was going to be good in it. I can't give you my two cents on The Big Kahuna because, thankfully, I got over Spacey by that point. But Verbal is an incredible character and I think that Spacey nails what it is to be Verbal. Now, it seems like it is low hanging fruit. Walk with a disability. Portray frailness. I get it. I could probably get that part. But Spacey is working this character incredibly well. I'm not talking about him hiding Keyser Soze. There's a way to play Keyser Soze without implying that he's going to be this dark character. After all, Verbal is the one who tells the audience and the police about who Keyser Soze is. There's no actual characterization for Soze outside of archetypes that we associate with Hungarian warlord. (Okay, I was actually weirded out by "Hungarian" as a choice of origin for a warlord. But again, I am woefully ignorant of such things.) I'm more talking about Verbal being incredibly playful the entire time. Everything we know about Verbal is fake. He's this guy who seems over-his-head. Now, Verbal could be snivelling. He's not. His character is in over-his-head, yet he still plays for dominance in the interrogation. He's also a character who is apparently emotionally available. These are all choices that Kevin Spacey as Keyser Soze is making. I like the idea that Verbal's real tragedy is that Gabriel Byrne's Keaton is just using him. Again, Soze doesn't care. He's one of these next level villains who found Keaton because he's the closest stand-in for Soze. It's pretty solid. The best part is that Soze's smart move is just to wait out the two hours before he's out on bail. Cool. Instead, Soze's choice is to intentionally prod this officer who is so desperate to get Soze by giving him hints about his lies. The barbershop quartet in Skokie, Illinois? That has nothing to do with Verbal's testimony. There's so many of these details that are just insulting his captor that make it fun. But that's why it's such a lovely drop when we find out that Verbal is Soze. It's the idea that Soze has a sense of humor and that none of this matters. There's this desire to almost get caught. After all, this is technically a catestrophic day for Keyser Soze. Soze spends the movie killing anyone who is able to identify him and the movie ends with the NYPD having photos of Keyser Soze. Mugshots! Verbal Kint was photographed for processing. Yet, he's still playing with this police officer because he can. It's fun. But there are a handful of things that are actually not that amazing about the movie. Kint is meant to be an unreliable narrator. He's a little bit of Nick Carroway in this story. Admittedly, he has more to do in this story than Nick does in The Great Gatsby, but he is still a little bit of an outsider in the story. Part of that means that we can only see what Verbal does...until he doesn't. Like, because he's Soze, we get these moments where Verbal shouldn't be able to tell us what is going on. It just seems sloppy, but that could tie into the idea that Verbal doesn't mind playing with the officer. Still, we miss out on the death of Fenster. Fenster's all of our favorite character, right? Like, he's so good. (Side note: This is the first time I watched The Usual Suspects) with subtitles and now I know what Fenster was saying. Sure, it took away a little bit of the magic, but that's the breaks.) It's fine. It just feels like Kint's narrative feels more episodic than it is a unified plot. All these major moments fly by and I realize that the movie is stalling a bit. The big thing is a bit of a cheat for the film. The best part of the movie is the reveal with the objects around the room. Knowing what I know about the film before this watch, I was looking for a way to solve all of the things that Kint is talking about. Singer never really shows the room in detail. We can only glean from Dan Hedaya's office that the character is a bit of a slob. Even the couch has stacks of files piled up. But we never get to see Kobiyashi. We never get to see Quartet or Skokie, Illinois. It's a really fun moment, but it's also a bit of a cheat to say "You didn't catch this?" because it was never shown to us. If we're meant to solve the mystery of Keyser Soze, a lot of the clues are hidden from us until the reveal. Still, the movie works. I mean, it works pretty great. Does it feel broey? Totally. I can't deny that. But who cares sometimes? This movie is an incredibly successful heist / whodunnit movie and it's pretty darned impressive. |

Film is great. It can challenge us. It can entertain us. It can puzzle us. It can awaken us.

AuthorMr. H has watched an upsetting amount of movies. They bring him a level of joy that few things have achieved. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed