|

Approved. It's always so weird writing the MPAA rating thing before there was an MPAA. It's about a murder. There's death. A kid dies...just randomly. It's got some divorce. One of the characters is obsessed with seducing this married woman, so keep that in mind. It's got a pretty negative view of humanity, if I had to be honest. So while there's nothing on camera that's all that offensive, the bleak portrayal of the human race isn't exactly something I want to share with my children. Regardless, Approved.

DIRECTOR: Michael Curtiz Spoiler: Of course it was all Veda. Veda was the worst. I'm going to go into this for a long time, but of course she did it. This all started when my wife and I were trying to think of a movie. My wife said something about the lady who murders people and then bakes pies. I had no idea what she was talking about. "You know, the pie murders?" Nope, I had nothing. She finally looked it up and saw that Mildred Pierce was on my Amazon wish list and that it was our anniversary coming up. Anyway, I love this movie, but the pie lady wasn't the murderer. It was just implied that she was the murderer! I don't know if I want to come out of the gate talking directly about Veda. Part of me wants to talk about how the human race doesn't deserve anything and that everyone is absolutely terrible except for the put-upon American housewife. (I can support the idea that the American housewife is put upon, but gee whiz this movie makes everyone else look terrible.) Curtiz starts the movie with Mildred at a point of despair. She's on the dock, ready to take her own life. It's heavily implied that Mildred murdered her husband and wanted to frame a "friend" (I don't even know how to explain the dynamic between Mildred and Wally). She seems like this terrible human being in a world of decent people. But by the end of the film, borderline everyone seems terrible and Mildred comes across like a bit of a saint. The thing that drives me nuts is that the whole flashback is started by the notion that the police were going to arrest her ex-husband, Bert. Not wanting an innocent man that she actually kind of liked to go to prison, Mildred claims that Bert is the most noble, sweet, and gentle human being imaginable. She has a really weird sense of what makes a good man because he literally is the worst. I'm never a fan of divorce or separation, but Bert is not a good man. The movie really implies that he's sleeping with is secretary. I would give him the benefit of the doubt, but he immediately goes to her when the separation begins, so point one to Mildred. He's mad that she's making money. And he's also mad that she's saving her own money to buy her daughter a dress. And this is where I question reality altogether. Bert really gets mad because Mildred buys Veda a dress with her pie money. Now, I can't deny that Veda sucks. I can't deny that one bit. The movie goes out of its way to make you really look down on Veda. But Bert's theory is that Mildred is destroying her daughter by buying her a cheap dress. I'm pretty sure that Veda from just being in a middle-class home has become completely spoiled. I can't blame that dress. If anything, that dress should have woken Mildred up to the fact that Veda is a terrible person who can't appreciate anything. But the actual purpose of that dress is completely fine. Bert, throwing a big stink about that dress and separating from his wife is absolutely absurd. But the worst part about it? It makes Bert right. See, the sleeping with the secretary is still very much implied at the beginning. But Bert's central thesis in that argument was that buying Veda anything is just going to spoil her and make her out to be a monster. That's exactly what Veda does. No one blames the divorce for making her a monster. No one blames the fact that she was always predisposed to be a horrible human being. Nope. It's all Mildred's fault apparently. It's not like Mildred was going above and beyond with the spoiling either. Veda seemed pretty talented at piano, so she got her lessons. She needed a new dress, so she bought her a cheap dress, which is all she could afford. Then the movie just doubles down on the horrible views of humanity, especially of the working woman. Veda, when Bert leaves, throws a bit of a hissy fit about not being able to keep up with the Joneses. But she ends the argument by saying, "As long as we're all together." Now, I'm pretty sure the read on that line was the Veda is being manipulative. She comes across as a spoiled, but sweet, girl until she marries this rich guy and fakes a pregnancy. But when Mildred reveals that she has a plan to become a restaraunter, Veda gets excited. It's not very flattering when she exclaims, "You mean, we're going to be rich?" But Veda does care where her money comes from at this point. She's actually excited for her mother. It's only when Monte shows up and the two of them form this kind of disdain for where their money comes from that the story really does get bleak. I know I don't live in 1945. I know. I get it. The idea of a working woman is so disdainful to everyone in this movie. When Bert leaves his wife, it's because she's the one making money by baking cakes and pies. That doesn't ingratiate me to the whole story. (By the way, if you ever want to argue wage politics in 2021, look how much Mildred can buy as a single-earner waitress.) But Mildred becomes this powerhouse in business and everyone is still grossed out by the fact that she works for a living. It's really this bizarre narrative that unfortunately existed (and probably still exists) in 1945. I don't know what Veda's plan was, really. Veda kept trying to kill the golden goose. Monte at one point refers to Veda as the prodigal daughter and that's an apt comparison. But the element of the prodigal son is in the name itself: repentance. Veda keeps going for these quick scores that are way more despicable than what Mildred does. I mean, I don't really feel like I have to comment on Wally. Bert goes from being gross to being halfway decent. Monte goes from being a good guy to being a monster. But Wally? Man, Wally borderline sucks from moment one. We see him being good-natured with his flirting (I'm being really forgiving right now). It's only the more we get into the story that we see that Wally has always been super-duper gross. So it's all a story about how the world is a terrible place. I mean, if I had to really nail it down, it's about the cultural theme about women in the workplace and how they never get the respect that they deserve. But to get that message loud and clear, we have to sit through just the most gross character traits that humanity has to offer. I mean, I love the movie. I genuinely love bleak things so it's not shocking that I'm all rah-rah about this movie. But it is fairly miserable when you think about it. Honestly, Mildred spends the movie trying to frame the wrong man for murder and perjuring herself to the police, and still, she's one of the most sympathetic characters in film.

0 Comments

Not rated, but this one actually involves cutting someone's hand off as opposed to just killing them. If anything, this movie really stresses how much killing is going on, despite the fact that the gore level is pretty light. Zatoichi takes some gnarly hits in this one, including an arrow through the arm and a sword slash that really should have put him out of commission. There's also some skinny dipping, but we don't really see anything because Zatoichi also wouldn't be able to see anything. Still, you know, it's a lot of killing. Not rated.

DIRECTOR: Kazuo Ikehiro It's really late at night and I just finished watching Black Widow. Part of me is writing this late because I want to get around to writing Black Widow sooner. But I also know that I should be cutting myself some slack because today was an insanely busy day and I have a feeling that tomorrow will also be an insanely busy day. It is so hard to get motivated to write about Zatoichi. There was a period a while ago where I considered writing about everything pop culture that I would absorb. This means every comic issue, every TV episode, every podcast episode, every book. The whole shebang. But I realized that I would burn out so quickly that it would defeat the purpose of even maintaining a blog. I'm really glad that I didn't do that now and I think that writing about the Zatoichi films is a reminder that writing about something that is so episodic only proves to be an exercise in frustration. When this is all over, I'll probably claim that I really like the Zatoichi movies. I have them on a very specific rotation, ensuring that I don't fly through them and not appreciate them. I'll watch one, get a little disappointed that it was very similar to the previous entry, and then watch a bunch of other stuff. But then another Zatoichi film would enter the chamber and I would get excited about it again. I'm also doing the same thing with Samurai Jack, but am way more disappointed with Samurai Jack. (I know. I'm just making enemies left and right.) Each one of these Zatoichi movies promises to change the script just enough to make it interesting. I really like the conceit that the movie always presents. With Zatoichi's Pilgrimage, the conceit was exactly what I wanted out of this franchise. Always thrust into action and adventure, the titular character laments how much killing he has done in his life. He's always been on the side of the law (with the exception of the cons he pulls with gambling), but regrets that this life has led him to this place within his soul that is at odds with his intentions. The movie starts off with the pilgrimage to visit the 88 Shrines with the focus of never killing again. But then the movie forgets this almost immediately and has him kill a bunch of dudes in a very similar fashion that he does in the other movies. He runs into a woman that might be the one to free him from this lifestyle, finds out that there is a gangster boss intimidating the people of this small farming village, and then dispatches the entire gang. The end. What was all that about visiting those 88 shrines to save your soul so you can officially put an end to the killing? The movie even calls him out on that first killing that happens almost immediately after taking the oath. He kills Eigoro, which is not really on him. It is like the gods placed Eigoro on Zatoichi's path to try to tempt him with a moral dilemma. But he never spirals out of control in that moment. It just leads him to Kichi, Eigoro's sister. There's almost a moment where the movie was going to embrace the conceit and allow Zatoichi to undergo a character change. With Kichi attacks Zatoichi with the blade and he chooses to allow the sword to strike him, I thought that there could have been something there. I thought that this was going to be this tale of him falling in love with Kichi as he sees Boss Tohachi slowly take over parts of the town. It could have been the Logan of 1966. I mean, Logan and the whole Wolverine mythos that was established on the comics borrowed heavily from Japanese Ronin stories, so it's not like that plot is unprecedented. It is just that the movie so quickly abandoned the main storyline. The movie is straight up called Zatoichi's Pilgrimage and that storyline just fades away in the first ten minutes of a pretty short film. Why? The titles, to a certain extent, are like rom-com titles at this point. They are there to simply differentiate entries in the series. Which Zatoichi movie is the one where he's on a pilgrimage before he starts killing everybody? Zatoichi's Pilgrimage. That's it. It's not about the soul-searching necessary to become a better person. And yet, there's something. It's very hidden in the background. It's like director Ikehoro really really wanted to make Zatoichi's Pilgrimage slightly special because, even though the script almost completely ignores the story presented within, Ikehoro allows for these moments of quietness to the movie. Here's the deal: If I summarized this film, it would follow, beat-for-beat, the formula of every other Zatoichi movie. I already gave those major moments above. But there are really slow moments where it seemed, just by holding the shot for a second longer than was necessary, that Zatoichi might have been going through something when he wasn't killing someone. There's nothing to be said in those moments. It's not like Kichi or the other farmers within the village are commenting that Zatoichi seems to be a little bit off. It's jus these cinematic shots that make it feel like the character is becoming one with the background. It's subtle, but I give points. Again, some of this could just be me and the fact that I over-read into everything. There's a really weird lesson that eventually stems out of Zatoichi's Pilgrimage and I don't know if it the message that the filmmakers wanted to tell. Like many of these movies, the final act comes down to Zatoichi versus the gang in one giant fight scene. Like in some of the other entries in the series, Zatoichi is fighting in the village he is defending. Like Seven Samurai (at least, early on in Seven Samurai) the farmers are cowards and will not help in defending their own village. Kichi begs and pleads with the farmers to get out there and to help Ichi, but none of them agree until one of the tertiary characters decides to grow a backbone. Everyone aware that this character is greatly outnumbered, but he's going to stand by Zatoichi, even if it means that it kills him. Now, normally a character that grows a backbone offers some help. He at least dispatches one or two guys, right? Not in this situation. That guy goes out, dies immediately. And Zatoichi looks at him like "Why would he do that?" yet salutes his honor and bravery. Aren't the farmers right to hide if the only guy who ran out to help after listening to a protagonist's pleas is killed immediately? Like, when Zatoichi honors the guy and admonishes the farmers, aren't they kind of right? Because Zatoichi got zero actual help and was mostly fine. Okay, he got an arrow through the arm, but I think that was just to make him look cool. I'm going to end this here. If the filmmakers of the Zatoichi don't offer me more to write about, anything else I add here is just ultimately filler. It's a fine movie, but it is so darned similar to every other entry in the series. Rated R for kid murder and kid death. I mean, there's other death, but the most memorable and gutsy death involves kid death. It's really tame for an R-rated movie, considering that the PG-13 horror movie exists in today's culture. But I can see the idea of this movie being R for 1980 as a real thing. It's only when you think about Poltergeist as a PG film that things get a little wonky. But it is kind of adorable what is considered a hard R for 1980. It might be a bigger commentary on America than anything else to consider a movie like this to be R-rated. Or the fact that I even question a movie about brutal murders to be something of PG faire. Regardless...

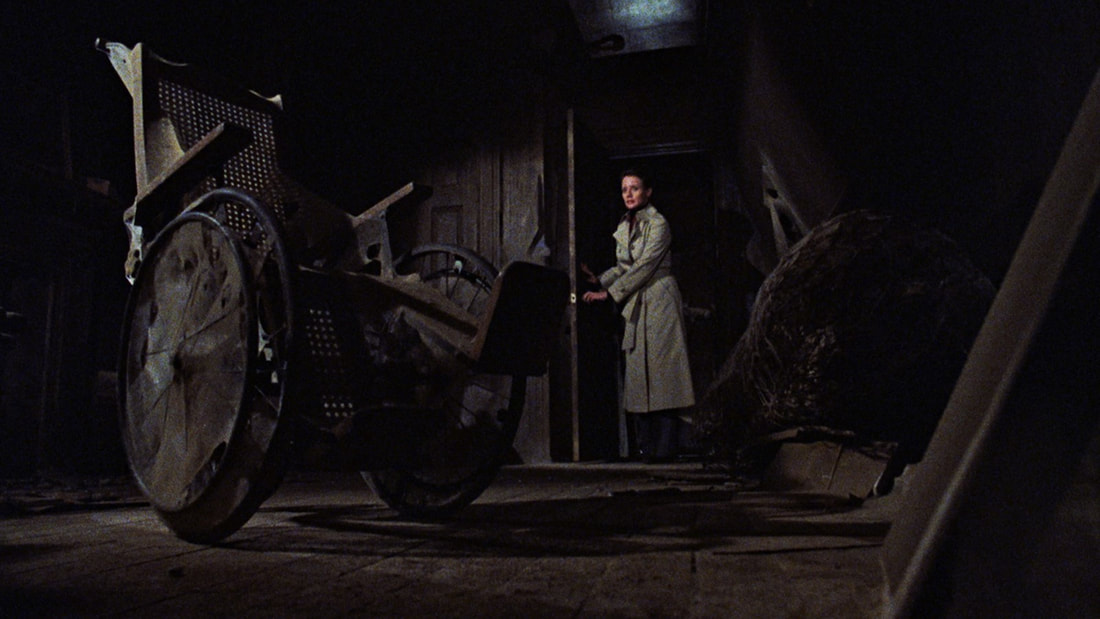

DIRECTOR: Peter Medak This movie is a classic, right? I feel like this is one of those beloved horror movies of yesteryear. It's the kind of horror movie that really appeals to the film nerd. But part of me might be projecting on the film because I absolutely dig the poster art. That might make me a bad film blogger, but that's something I've never denied in the four years that I've written this blog. (Also, I know that I watched most of Poltergeist two years ago, but did I watch the whole thing enough to have written an entry? These are the random thoughts that interrupt the flow of what-should-be a naturally progressing blog entry.) I knew nothing of this movie outside of the fact that it had the wheelchair on the poster and that people treat it with a modicum of respect. When I saw that this was a movie about General Patton fighting oogetty-boogetties, well, that ended up just being a treat. Listen, The Changeling is a perfectly fine movie. I'll not complain about it. Heck, I keep throwing Poltergeist in here as a comparison mainly because it would make a fine double feature with The Changeling. There's something about the older haunted house movies that really scratch a pretty exciting itch. I can't help but make the comparison to the gothic novel that we kind of got a resurgence with when it came to the horror movies of the '70s and '80s. I'm going to be writing about a feeling of synergy that I can't quite put into words. As much as I still appreciate a good haunted house story set in the contemporary era, there's something about setting a story in 1980 and coupling it with an evil home that makes it worth while. I think it is the idea of the cell phone and the creature comforts of today that don't mesh quite well against the spiritual realm. Maybe it is because we are inclined to turn to science in the contemporary era when the characters in a 1980s horror movie just instantly dive into the realm of fantasy and the afterlife. Don't get me wrong, John Russell first looks at the pipes to explain the goofy noises. But he never really has that stage of trying to capture the ghost using EMF or whatever newer films tend to lean on. There is no internet scene. Heck, I have to imagine that George C Scott probably felt pretty good that he was using the library's microfilm database to look up the history of the house. It had to feel like the future compared to the halcyon days of Vincent Price and The House on Haunted Hill. What this all inadvertently does is make the mood of The Changeling a powerhouse. It really doesn't have to be that good of a movie. In fact, there are a handful of things in this movie that are plain ol' dumb. But it is that atmosphere of 1980s grit fighting the macabre history of the early 1900s that really just works. 80 years is a long time, but it isn't such a long time that it can't interact with the world of today. Sure, it kind of goes off the rails with the senator plot. I really wanted to like the senator plot. The really great haunting movies, for me, are the ones where the protagonist has a chance to escape the fate of the house by investigating the history and putting the ghost at rest. Really, it's a fantasy-led detective story that should ultimately come full circle to the events that are happening to the cast of heroes. This is what made The Ring so great at the time. Maybe it is the feeling of being kind of antiquated (although I loved The Ring the most when it first came out). But when The Conjuring movies do what they do right, it is usually because it is all old timey. That feeling of otherworldliness is often lost on today's society. This is me sounding like a sad old man who isn't even 40 yet, but everything now is about the Internet and making things bigger and scarier. The idea of the gothic horror is kind of passé for our culture. Again, we can only revisit it through nostalgia. But I suppose I should talk about what doesn't really work in The Changeling as well. See, it's a perfectly fine movie...if you shut your brain off. (Trust me, I'm very okay with doing this. I'm not saying The Changeling is for dumb people. But the movie asks you to go along with the ride and simply accept a lot.) John Russell has a traumatic inciting incident. He has the best family in the world. I love how the story needs for Russell's car to breakdown while simultaneously showing the family at their best. So instead of having a complaining family pushing a station wagon down a snowy road, they're somehow enjoying it. Honestly, this family goes from shoving a multi-ton (I think?) vehicle in crappy weather to instantly transition to giggly snowball fight. It's pretty hilarious and I instantly didn't take the movie seriously. They had to get wrecked at the height of John's happiness, but that accident needed to have an element of John blaming himself. And for a while, it really seemed like John's internal conflict was getting over the death of his family. After all, Joseph really plays up the dead daughter haunting by having the ball constantly remind him of the death of his little girl. But the second he finds out that the haunting isn't done by his daughter, his family really takes a back seat. Now, we could call this character growth. But there isn't a direct tie between moving on from his grief and purging the house of this damned spirit. (Not like I'm swearing there, although it kind of works both ways.) Then there's the mislead. There's the girl who dies by the coal cart. I got invested in the girl who dies by the coal cart. Now, I'm going to play devil's advocate here. The girl who dies from the coal cart in 1909 could act as a cautionary tale. If John decides to ignore Joseph, he could end up like the little girl in 1909. But I'm going to fight that reading of the story because, like John's family, the little girl never comes up again. And the movie devotes so much time to this story. John discovers the little girl's backstory when he finally accepts the call of the goddess and continues into the attic. The reward for his courage is the girl's story. That story needs to have value. Instead, it is just this side story that ends up being a complete red herring in the narrative. All this comes down to the fact that this is really a short story about a senator who profited from the death of a little boy that he never met. There's not a lot of meat there. I mean, the meat that we got is good. It's like quail. What story there is actually is fun and impressive. It's an interesting and deep melodrama about privilege and corrupt government. Okay, but it doesn't say much about it. Also, we never get the full notion that the senator knows what's up. Sometimes the movie implies that he knows all about the handoff. Sometimes, he can't believe his father would be capable of murdering a little handicapped kid in a bathtub and seems mortified by the accusation. It's all very muddy. But all we know is that he goes up the stairs of a burning house to confront Joseph... ...and Joseph doesn't really care what John did. That's a weird moral of the story. Joseph has tried to tell his tale to all of the inhabitants of the house. John actually responds and does his best to remedy this situation and put Joseph's soul to rest. (I just realized I'm complaining that the demon is being a little unfair at this point.) John takes a major religious and philosophical leap to get Joseph's soul free from the house. But each time that John returns, the house just gets more aggressive. Was John supposed to kill the senator? The movie kind of implies that's what Joseph is mad about when he returns. John presented all of the information to the senator and gave him all of the evidence and then hoped for the best. Yeah, from a ghost's perspective, that might be a lame decision. But I would argue that John killing the senator would only evoke more rage from Joseph. I suppose that there's a far-fetched scenario where John leads the senator to the house, yells "Surprise" coupled with an expletive, and then allows Joseph to rip him apart. But that really makes John the bad guy of the piece. But all of that is more of a commentary on the genre. There's always a rush to unravel the mystery of the ghost and the ghost rarely seems to be at peace about that investigation. Maybe it is because ghosts are insane or whatever canon that particular movie follows, but I honestly believe it is because that's what we want. We want our third act to be bannisters on fire and old-timey wheelchairs trying to murder people. And it works. That's what The Changeling is. It's a goofy old horror movie that ticks a lot of boxes, despite not having a ton of content. I enjoyed it, but I also don't know how much I could put it in the "great" column. PG. You know, those movies that have nudity and a sex shaming plot that often end up with a PG rating? Oh, I can't forget the murders by garroting that are also in this movie. That's pretty typical to get an R-rating as well. I mean, the entire SPECTRE training ground stresses that they train with live ammunition. These are all things that are pretty typical of a PG rating. Okay, sure, I watched this movie as a kid multiple times. But look how I turned out. You know what? Back that up. It's James Bond PG. Also, the movie has a pretty backwards attitude towards the Romani people, referring to them as gypsies throughout.

DIRECTOR: Terence Young For years and years and years and years, I considered From Russia with Love to be the greatest Bond movie. Heck, there was a time in my life that I considered it to be one of the greatest movies of all time. (I was in a bit of a Bond phase at the time.) But since I got this blog and started teaching my film class, I've been trying to watch these movies with a bit of a critical eye. And I have a confession to make: the last time I watched From Russia with Love, I got a little bored. It was in that moment that I thought that my new favorite Bond movie was Casino Royale. That slight dip in ranking made me question everything I thought about Casino Royale. I thought that maybe I was being a snob. After all, while From Russia with Love is probably one the better Bond movies by a lot of people's opinions, most people give Goldfinger all of the props. But maybe all it took was some time away from the film to appreciate it anew. While I can still confidently say that Casino Royale might be the best Bond film, From Russia with Love is the best that Classic Bond has to offer. While writing about GoldenEye, I stated that there was a tonal shift between Licence to Kill and GoldenEye that was a firm break from what I consider Classic Bond and nu-Bond. In my head, these are different franchises that wink at each other from time-to-time. But I think both Classic Bond and nu-Bond owe a lot to From Russia with Love. As much as I love James Bond movies, they have one really dangerous flaw that is hard to reconcile with: they constantly want to out-do the previous film while holding aggressively onto the formula. What ends up happening is that these film become outrageously cornball, as can be seen in stuff like Moonraker or Octopussy. Heck, even Diamonds are Forever is a far-cry from the Ian Fleming source material. I'm not saying that Fleming's writing was the most tame stuff in the world. His final full length adventure has Bond getting amnesia and living in a Japanese fishing village after killing Blofeld. It's not like he shied away from melodrama. But the James Bond of the film franchise was almost a cartoon character. I'm not saying that is a bad thing. I fell in love with the concept of these films, so who am I to complain about absurdity? But From Russia with Love is this really special thing in the timeline. It is a very different film from its predecessor, Dr. No. Part of this comes down to setting and how setting influences mood overall. But moreover, Bond grows into a more international character in From Russia with Love. In Dr. No, the titular villain comments that Bond is "...nothing but a stupid policeman." While Bond certainly isn't stupid, Dr. No kind of treats him like he is a policeman. He's following clues and it seems like he stumbles upon something that is far greater than anything he's ever dealt with before. But the sequel, From Russia with Love, makes his world that much bigger. The events of the first movie now seem commonplace for him. And this is what makes From Russia with Love this perfect nexus of Ian Fleming's character and what Broccoli and Saltzman wanted out of the character. Fleming almost reads like a goofy Tom Clancy novel with a healthy dose of racism and sexism woven in. But central to his story was the world of international espionage. When we think of Bond, we often think of Bond versus the Russians and the tenuous diplomacy of the Cold War. From Russia with Love is where we get that idea. While the films revisit Russia as the villains throughout the series, no time is closer to the actual situation than what we see in From Russia with Love. The Russians aren't moustache twirling in this movie. In fact, Terence Young portrays them as equally capable as Her Majesty's government, both being played as dupes by SPECTRE. It's amazing that I'm so just cool with SPECTRE. Fleming, an author who had a history with espionage in reality, wrote this organization (Okay, the original was SMERSH) that was an evil comic-booky shadow organization that just was crime-for-crime's-sake. Yet, so much about this is about the politics of two superpowers that are not allowed to shoot at each other on land that was tenuous. And it somehow works. The fact that SPECTRE is the bad guy gives it a complexity while also making it borderline cartoonish. Both sides of the Cold War are allowed to be sympathetic because they are both being manipulated by this shadow organization that you are asked to shut your brain off for. If you think I'm being flippant about SPECTRE, by the way, think about the Kronstein death scene. It's very over the top. Also, does Blofeld just have a fighting fish budget so he can keep using them as a metaphor for SPECTRE as a whole? I don't know. One of the great Bond debates is about the Bond girl. I always find this to be gross. For being such a die-hard James Bond fan, it always puts me off ranking the Bond girls. I easily have a least favorite Bond girl with Christmas Jones from The World is Not Enough. But I just realized that Tatiana Romanovna might be my favorite Bond girl. Romanovna really sits in this really interesting space. She is outside of the world of espionage. In many ways, she acts as the audience's avatar. Bond can't be our avatar. He has it all too much together. But she is this woman who is only trying to do the right thing while not getting shot. It becomes clear that she genuinely has feelings for Bond, despite the fact that it is a dangerous thing to fall in love with James Bond. She puts on this strong front and gets a job done that she is woefully ill-prepared for. Yeah, there are moments where she comes across as the fragile woman, but most of that is under the influence of sedation. But the biggest thing is that she never comes across as a silly Bond girl. She isn't given this over-sexualized name. While she's obsessed with Bond, there's a reason that she acts the way that she does. And these are the glory days where you can still lie to yourself that Bond isn't only using these women for Queen and Country. (I mean, he totally does. It's straight up his mission. But there's a hint that Bond might actually love her back.) Similarly, the Q-Branch fight, coupled with the Red Grant fight, all seem within the realm of possible. The relationship between Bond and Q hasn't been started yet. I know. That's my favorite part of these films too. But Bond's first gadgets all seem kind of practical. A briefcase with a knife and an anti-tamper device? Cool. That makes sense. Even Red Grant establishes the idea of the Bond heavy that he has to take out. But Red Grant is one of those Jaws-like characters who actually just seems like he's a really strong and well-trained dude as opposed to completely gimmicky. I love Robert Shaw in this movie. As much as people see him as Quint in Jaws, I always thought of him as Red Grant. (For you Man for All Seasons folks out there, simmer down.) There is just so much that works in this movie and it's all because it is the toned down version of what Bond would eventually become. The fights seem larger than life, but plausible. The bad guys are great and nuanced. There's an attempt to ground the world of this grandiose sci-fi world that would eventually get so big and overinflated. There's no giant fight sequence, which makes the smaller fight sequences all that much more powerful. Honestly, the series need not get more exciting than Bond taking out a helicopter that is chasing him over a mountain. Also, the supporting cast is just great. I actually get bummed when Kerim Bey dies because he's one of those all time great supporting roles. As much as Casino Royale will take the cake, I was right to consider From Russia with Love one of the great Bond films. It's solid and ticks all of the boxes while offering a slow and interesting narrative. Sure, it also introduces plot holes for later films, like General Gogol's alliances or why there even is the St. Sofia scene. But it doesn't matter. The movie really works. Rated R for a lot of language, off-screen drug use, off-screen adultery, and mild violence. Also, you really have to be comfortable with your own mortality coupled with the mortality with the people around you to make it all the way through this movie. It's a gut punch and it's going to try to get you in all of the feels. I don't know if you can really make something R rated by that logic, but don't expect the lightest comedy from this outing. R.

DIRECTOR: Alexander Payne Man, what a difference a decade makes. I'm 38 now. I have a wife and four kids. I thought that this was an okay movie a decade ago. I certainly didn't think it was worthy of an Oscar nom. Back then, I didn't know who Nat Faxon and Jim Rash were, let alone that I would consider Jim Rash to be a genius a couple of years later. But at 38, this movie hits and hits hard. It's not like I have Matt King's life in the least. I don't think that wife is cheating on me. I know that she's not in the hospital dying. I'm fairly certain that my kids don't live the lives of these kids. But this movie just ripped me apart this time. The funny thing is, despite the fact that I watched the same movie twice, it seemed like two very stories, despite the fact that the plot was what I remembered it being. In my head, this was the story of obsessive Matt King and the fact that he is torn between stalking his spouse's lover and having to keep it together for his kids. When I watched this the first time, I thought about this was about a man's toxic elements consuming him until he realized he needed to let things go. Boy, I was wrong. Now, I know what this is going to make me sound like a bad person considering what I just said, but Matt King is kind of a flawed saint. Heck, I would probably do exactly what he did in a similar situation. Matt is hurting for the entire movie. From moment in the film, he is dealing with a spouse who is dying. While most movies deal with the crisis moment coming right before the climax, Matt has already dealt with his crisis moment before the movie even began. Elizabeth's accident was his Ebenezer Scrooge moment. He discovers that he has been lacking as a father and as a husband and he has committed to change. It's not that he was a bad guy before this. It's just that his priorities were all screwed up. Not evil or anything, but someone who has made small compromises and had to deal with the consequences of those compromises. Now, in this world, Elizabeth is terrible and my wife is not. But I can see myself napalming the world given the situation. And when he discovers his wife's infidelity, that's where the new story begins. He made his choice and there's an almost Twilight Zone style irony to this discovery. He made this huge decision to become a better person and the universe dared him to renege on that decision. Sure, the movie becomes heartwarming after that. It's because of his wife's toxicity that these people come together. I feel like I'm going to go real sappy now and I really don't want to. But there's something that reminds me of the aftermath of World War II. All this tragedy and misery that anyone would avoid given an opportunity leads to something positively vital to society. It is in this moment that I realize that this is a movie about bonding over shared toxicity. Matt is so disappointed Alexandra and in himself for letting Alexandra become the person she is. But when they realize that there's a reason for Alexandra's dark turn and that it is a shared mourning, that makes things oddly better. The rest of the movie becomes this very dangerous tightrope to walk. Matt knows that he has to be a better person than he wants to be. In my head, he wants to go scorched Earth on everyone. Scott, Elizabeth's father, is borderline begging to get ripped apart. He becomes this litmus test for how far a person can be pushed. The right thing to do would be to hold back, allow Scott mourn the death of his daughter by allowing Matt to be the punching bag. Yet, as an audience, that seems like a betrayal. Because Matt is our protagonist and avatar for going through the process of grieving, we want him to have a moment of catharsis that doesn't really come. It's that sacrificial element that we all experience in this moment. Because the movie really does have a happy ending, despite how depressing the film is. (Part of me kept rewriting the story in my head that allowed Elizabeth to wake up from the coma and the story oddly became more tragic, despite a miraculous recovery.) But Matt's new goal isn't necessarily to find Brian, Elizabeth's lover. That's the quest he is on. In the same way that Frodo's quest is to destroy the One Ring, his real quest is to show that mortals are ultimately good and capable of resisting sin. Matt's quest is to find Brian, but his real goal is to ensure that Alexandra sees that the world doesn't need to be about revenge or indulging selfish goals. Those moments are so tempting and Matt even is on the verge of losing his soul in the process of the whole thing. That's what I really indulged the first time I watched this, not knowing the importance of being a good role model for the kids. When Matt confronts Brian at his cabin, he starts letting his true motivation peek through. But he still holds back. And that's when the temptation about the money becomes something that forms this new element of the story. I know more about Hawaii now than I did a decade ago. I'm not saying I know everything, but I know something about the culture from podcasts and editorials. There is a really complicated cultural dynamic in Hawaii. I always thought of it as just another state, just far away and tropical. But Hawaii, um, maybe shouldn't be a U.S. state? Maybe it should be independent. The struggle exists between white people holding power and the indigenous people being seen as second class citizens. I know, what else is new? There's this story that is publicly about Matt's morality being on trial. Matt knows that his land is complicated. While legally his, there's something about the King family owning such a large plot of land in Hawaii that is kind of gross. Now, Matt's stance has always been on the low-key moral side. He kept the land as-is because it preserves the natural beauty of the landscape. But laws have forced his hand into deciding something that would be a morally neutral decision. But there are still consequences to this action. He has to sell the land, which would make him rich. But by selling the land, he is betraying the Hawaiian people and changing the entire dynamic of the region. And that is all going on while he's dealing with the medically dubious situation with his wife coupled with an affair that he just discovered. Any man would crumble under these situations. Matt doesn't come across as a hero, but he really is. It's because of his real flawed reaction to everything is what makes this movie excellent. He is a good person and the movie intentionally rarely gives him credit for his good actions. Sure, the end at the family vote, there's that moment where we can pat him on the back. But the entire movie is this guy who is acting against his own self-interests and how the world turns out to be a better place because he did the right thing when the easy thing would be to do the wrong thing. God, I was so so wrong about this movie a decade ago. I knew it was okay, but the movie is kind of genius. It is a gorgeous film that acknowledges what privilege is about while stressing the importance of sacrificing oneself for others. Well done, movie. Well done. Approved, but despite its fairly light tone, it definitely isn't for kids. Like, I really want my daughter to read this book and watch this movie. I even think that she would understand the majority of the content. But would I want to introduce her to rape charges in the light of institutionalized racism? I've been working to instill my daughter with anti-racist philosophy, but the rape thing might go a little too far. Even though the film doesn't show too many graphic things, it's still a heavy discussion for a nine-year-old. Also, there is a decent amount of off-screen death and violence, not to mention hateful uses of racial slurs.

DIRECTOR: Robert Mulligan This is an intimidating one. Since I teach both English and a film class, I often talk about the literary and cinematic canons. It's my belief that there are very few books in the literary canon that also have a movie counterpart in the cinematic canon. The one exception that always comes to my mind is To Kill a Mockingbird. I've seen this movie so many times. When I taught eighth grade, I would teach To Kill a Mockingbird and show the movie while it was going on. Then I found out that one of my older classes never got to the novel, so I taught it again. But I realistically don't see myself teaching this book again for a while. But even without being a teacher, I had seen this movie a dozen or so times. It's one of those absolutely life-changing films. But I can't deny, part of me is going to talk about the novel and maybe even Go Set a Watchman. There was a time, heck even recently, when I thought of To Kill a Mockingbird as a cautionary tale of what we were and a reminder of how far we've come. That was a thing that was always, "Don't rest on your laurels or we could return to this rotten time in history." My bleak outlook is that we're not very far from this moment anymore. It was way more haunting this time. I mean, I have always viewed To Kill a Mockingbird as one of the greatest criticisms of white power. But in retrospect, it would probably be pretty dangerous to watch the film in today's society without thinking that this could and still would happen. The tale of Tom Robinson is one of those stories that is so clear cut that I'm floored that Harper Lee decided to make the jury give a guilty verdict for the crime of sexual assault. I mean, it's the ending that works. Perhaps that's the part of me that loves bleak storytelling, but it only really works with Tom still being convicted of rape. (I know, Go Set a Watchman had Tom acquitted and I think the real Atticus might have actually gotten Tom off, but it works as a narrative structure pretty darned well.) But maybe it is my brain playing tricks on me. When you watch a billion movies and read a billion books, stories sometimes get mixed together. I've read the book multiple times, so I hope my brain isn't failing me. But one of the major differences is how Tom dies in the movie versus the book. In the movie, almost immediately after Tom is convicted and transported to the county jail, he is shot by a police officer while trying to escape. The same thing happens in the novel, but the movie stresses that the officer shoots him once, trying to injure him but accidentally killing him. It's very sad, but it is a tale of how Tom finds there to be no hope in a white dominated society. Sure. That's a message that is central to Lee's story. But the book, I'm fairly certain, has him riddled with bullets. There's no pretense of him trying to escape. It's punishment for the questioning of a white man's integrity. I think I wanted my daughter to watch this (which I have yet to do!) because the story is from a child's perspective (kind of. It's Adult Scout looking back on her childhood). The film doesn't cheat and give Scout any great knowledge about what is going on. She knows things are terrible, but she also sees things as a six-year-old would. Boo is a ghost story until he's not. Walter Cunningham never stops being a bad guy because he brought a bushel of hickory nuts over one time. Mrs. Dubose is this wicked old racist because she yells at Atticus and the kids all the time. (That part is never resolved in the movie. She's introduced as an awful old bat and is never seen again.) There's something absolutely brilliant about how this was the summer that didn't change Scout in the moment, outside of the fact that she views it as the summer that Jem had his arm broken, but instead formed her adult life. She learns these life lessons that never really come into play during the course of the story, but rather for who she is going to be in the long haul. There is this one moment where she has this epiphany about what Atticus was trying to teach her and it is the titular line. Her realization that Boo Radley is kind of like a mockingbird is a sentiment wise beyond her years, but that's okay. The movie needed her to restate the theme and since it is the end of the film, it's implying that she's growing up with that line. But Gregory Peck as Atticus Finch might be one of the all time great performances. It's a little unfair because this happens a lot. I always picture Anthony Hopkins when I'm reading a Thomas Harris novel. I always picture Gregory Peck as Atticus Finch. But I know that Harper Lee thought of Gregory Peck as her father. (For those not in the know, while To Kill a Mockingbird is technically a work of fiction, it is semi-autobiographical.) Peck was one of those all time great actors. We were watching Staged (on Hulu right now, if you are curious) and Tennant and Sheen refer to Judi Dench as ethereal. She's one of those next level actors that just becomes a presence in everything that they do. Peck was one of those people. He was famous, but I don't even think he was as prolific as Dench was. But I know that because of To Kill a Mockingbird, anything I saw Peck in I thought of Atticus Finch. Unfortunately, that includes the first Omen film, but I don't even care. Both of those movies own. To Kill a Mockingbird kind of cements Atticus Finch as the ideal father. He becomes the archetype, but even more so, we want Atticus Finch to be our own dad. It's funny, because Jem, in his early teenage years, often resents what his father can't do rather than what he can. I had an older dad. I can imagine yelling at my dad for not playing football for the Methodists (if I was into football or was Protestant). But there's one moment that is such a weird staple for the film. I have seen this scene referenced in all kinds of places, but my brain is flashing to a page from a Goon comic, where Atticus has to put down the dog. There's a concept here that only my adult brain can really grasp onto. It is what Lee was going for in Go Set a Watchman (admittedly, an insanely polarizing novel). We never really know our parents, do we? We know a lot about them, but they are always our parents to us. Mrs. Maudie knows that Jem is being an idiot complaining about playing football. But when Heck Tate comes over with a rifle and asks Atticus to shoot the dog, Atticus might have just as well flown away and Jem would have been just as shocked. The dark side of that, of course, is Go Set a Watchman's revelation that Atticus had been a member of the Klan. Just writing that sentence bums me out to no end, but it also is about the fact that we tend to form ideas of who people are without understanding that people have both talents and flaws that we could never possibly understand. I never think of Robert Duvall as Boo Radley. He does a fine job. Sure, he's barely in the movie. (I don't really want to write too much about Boo because that's the job of my eighth grade class, who always finds Boo to be the most fascinating part of the book.) But Gregory Peck becomes Atticus Finch and, it should be noticed, that Brock Peters is always Tom Robinson for me. He's in a bunch of Star Trek movies. It doesn't matter. I see Admiral Tom Robinson at the Khitomer Accords every time. Do you know why? It's when Tom is giving his testimony. Like Boo Radley, you hear a lot more about Tom Robinson than you actually see of Tom Robinson. But he sits there with this dignity. He has trust that Atticus is going to do everything he can to ensure his freedom. But when he gets up on that stand and tears get in his eyes, that is a performance. It gets me. (Again, I can't cry unless it's a Christmas film, but that doesn't meant that I don't get moved.) He's crying because he's on trial, but he's also crying --for a really messed up reason --because of what Mayella Ewell did to him. Because one thing that is odd to think about is that Tom is the real victim of sexual assault here. Robinson still pities Mayella (which is what ultimately seals the deal for the jury), but he also thinks that he was just there to help do something that our society should see as basic. But this woman starts kissing all over him and he knows that, socially, he can't do anything about it. It's not like he's a single man. It looks like he was in a happy marriage with a bunch of kids. But because society understands that a good Black man is worth less than an evil white family, he just had to take it. And Brock Peters got that so much in that moment. It's insane to think of how powerful that moment was. There is one line that I really wish made a bigger splash in the movie. It's the concept of doing the right thing, despite the fact that you know that you are going to lose. That's what the last administration did to me. I knew that I was going to annoy people when I called out Trump on his evils. I'm in a place where I'm alone in these beliefs. We're surrounded with Trump flags still and I know that people give me the side-eye when they're being polite. But that's kind of what it is. I think of that line. The line I have a harder time with, unfortunately, is the walking around in people's shoes for a while. Maybe it was because I did walk around their shoes and still made judgements or maybe we've just gone too far as a society, but that's something I still need to work on. Regardless, To Kill a Mockingbird is one of those powerhouse films. While I'll probably never have it in my Top 5, it really deserves to be there in some regards. It really is a fantastic film. |

Film is great. It can challenge us. It can entertain us. It can puzzle us. It can awaken us.

AuthorMr. H has watched an upsetting amount of movies. They bring him a level of joy that few things have achieved. Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed