|

R, because it's a pretty raunchy comedy. There's one of those jokes that's such a gross out joke that I don't even want to write about it in words. The words themselves make me feel a bit icky. The movie is overtly sexual, but I don't actually remember seeing any nudity. There's tons of language and innuendo all throughout. Big surprise, the character played by Seth Rogen does a lot of drugs. It's a stand out raunchy rom-com. R.

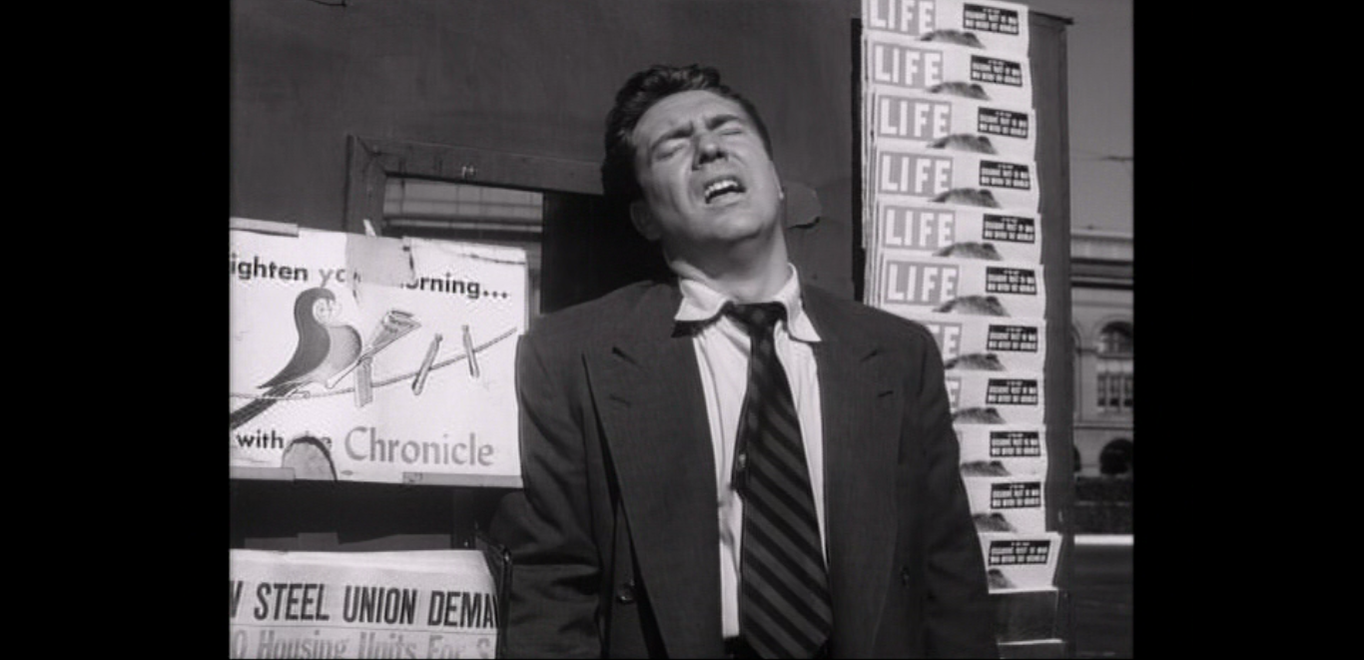

DIRECTOR: Jonathan Levine It's so funny that my sister-in-law really wanted to see this. My sister-in-law lives very clean and very wholesome things. She has probably seen more Hallmark Christmas movies than the people at Hallmark themselves. She was referenced on a podcast for her absolute devotion to Hallmark. When I saw the trailer for Long Shot, I immediately said that she would not care for this movie. I don't think that she ended up seeing it. But after I saw it, I can officially say that I was right about how raunchy the movie ended up being. Seth Rogen might be his own worst enemy. He has made so many great raunchy comedies that he has set the bar remarkably high. There's something very difficult about getting comedy right. It seems like such a specific point point of factors that go into making a comedy work and there's probably such a small payoff that it might be impossible to tell if a comedy is going to crush. Seth Rogen has made a handful of actually game-changing comedies. He was great in Knocked Up, which has the added bonus of being a rom-com. But he's also one of the forces behind Superbad, which every raunchy movie has tried to imitate since then. I would cite Neighbors as one of those game changing things, but I think that's more on me. Just because I like that movie doesn't mean that I have the power to movie it into the comedy canon...that's too much power. But I'm saying that the man has made some brilliant movies in his day and so when a movie is just adequate, it's a bit of a bummer for him. If Long Shot was his out-of-the-gate movie, there would be a lot to talk about. Every jokes pretty much lands. I never got bored. That's the role of a comedy. Heck, I should probably throw in that Seth Rogen and Charlize Theron somehow make a convincing couple. That was literally some of the publicity for this movie, how these two characters are going to be considered a convincing relationship when he's such a schlub and she's Charlize Theron. I know. I hate shaming people for how they look. But Rogen is one of the people behind this movie. He's producing it and he's acting in it. He knows his own reputation. I suppose the other side of that coin is that he's the one who can have romantic scenes with a Hollywood starlet, so let's put all that sympathy in perspective for the moment. But in terms of being a romantic comedy, it wins more points than it loses. Again, as I keep pointing out, I find romantic comedies often insipid. I know I doth protest too much, but that's the way I feel about a lot of them. The fact that I was never actively annoyed by this movie was great. When people put the funny first and the formula second, a lot tends to work. It's not like Long Shot isn't formulaic. It actually really, really is. But the comedy is still what is honed and perfected for the most part and that's pretty great. But I do want to analyze the film, not just blah blah about it. (That's my new phrase. "Blah blah." It fills up space and gives me a bit of momentum to figure out what I'm going to say.) I find it interesting that Seth Rogen may be aging with his characters. If the archetype of Seth Rogen was his character in Knocked Up, a fat drug-addicted waste of space, it's interesting to see that Seth Rogen is now a fat drug-addicted productive contributing member of society who has strong political views. I hate throwing around the word "fat" because I don't like to fat-shame, but the movie really rides out the physical appearance of Rogen so I'm only semi-apologizing. Rogen has been and always probably will be a character actor. It's absurd to imagine him without some kind of drug culture behind him. He's about normalizing drug culture. Again, tea-totaller here, so I can't exactly jump on board this train. But Knocked Up was made in 2007. This is the Bush administration if I'm doing my math right. This is easily searchable and I should be doing a better job as a blogger right now, but I'm not going to get distracted or self-flaggelating. 2007 sounds like it wasn't that long ago, but it's thirteen years ago. That's actually kind of a bit of time to pass. Rogen's only a year older than I am. He's 37. That means, in 2007, he was only 24. I'm trying to think of myself at 24. Yeah, the culture was different then. The 2000s were this moment in history where you were either really political or not at all political. I know it sounds like I'm talking about 2020, but trust me for as much as you can. Partially, there's probably this subconscious commentary on the role of the loser character. I love that we're shifting away from physical type to determine background of characters. Rogen is still playing his lovable goofball, with his fun drugs (don't do drugs!), but he's imbuing this storytelling with an element of responsibility. I'm goign to step out of myself for a second because I think it behooves me to have a sense of perspective when I go deep diving into analysis. I admit, he has to have a reason for Charlize Theron to like him. It would be absolutely bizarre for the Secretary of State to sleep with the guy from Knocked Up, but I like to think that there is more going on there. Fred is a 21st Century male in a time where the world is falling apart. I would like to remind you that I'm writing this from my basement, which is part of a house that I have not left since Friday. There is this commentary running in the background of the need to stand up to a system that does not listen. While the politics in Long Shot are sophomoric, that simplified form of government reminds us that we can't just afford to be lovable losers. Yeah, it's a rom com and we want the two leads together, but that doesn't allow Fred to back down on his beliefs. There's this great moment where we know that he's completely enamored with Charlotte. Yet, the second she starts backing down on her campaign promises, he holds her accountable. Things are more important than just the happiness of the one. I also applaud the fact that he's not totally right for the way he handled it. Sometimes, life gets super messy. I adore that the challenge is greater than simply a misunderstanding. There's this objective good in the world and the two want to fight for the this thing that others might consider hard to pull off. Long Shot isn't a genius film. There are times that I straight up got bored with it. As a raunchy rom-com, it tells the jokes that is should. I laughed out loud a lot. I never really found myself giving a forced laughed. But I didn't ever guffaw either. Instead, it's just a good time. The worst thing is probably Flarsky's clothes, but that's part of the story, so I'll forgive it. Oh, and Dan Harmon and Rob Schrab would probably hate one of the jokes. It's the joke where someone looks like something, but the director and writer scripted all of that so it's manipulating too much. If you are a Harmontown fan, you'd probably get it.

0 Comments

Rated R. This is an extremely intense and vulnerable film. It's not easy to watch throughout. The movie deals with sexual violence, including rape. There's also pretty graphic imagery with consensual sex as well. The language is peppered with language throughout. There is a murder involving a child. Sexual situations are rarely implied, showing nudity and the sexual act itself. It's a pretty well-deserved R.

DIRECTOR: Kimberly Peirce It's officially lockdown in our house and most of the world. I stepped outside to get the mail and I swear it felt like the zombie apocalypse. I know that things are still happening out there, but we're just trying to do our part. I'm prefacing all this 1) for a sense of continuity and 2) because I'm a bit of a coward. Boys Don't Cry might be the most challenging thing that I write about for a while. I basically know that whatever I write, no one is going to be happy with it. I have infamously not fit into a category. I've always wondered if I'm alone in this. To half of my friends, I am far too progressive and liberal. I think of myself often as a pro-life democrat. Instantly, I lost a lot of my readership. To the other half, I am far too progressive. How dare things be questioned? I would claim allegiance with moderates, but moderates all have different tastes in things. I like that about us. It means that we took each issue and have a stance that isn't just a party line. But that also means that this entire thing that I'm going to write is going to be hippie-dippy to some and transphobic to others. I can't win, so I'm just not going to publicize that I am writing it. In 1999, I should not have watched this movie. I was just going into high school and I would have gotten the worst possible interpretation from this movie. That actually might be the bravest thing about this movie, making it in the Wild West days of prideful political incorrectness. I always hate old me. I like me in the moment, but old me is always terrible. I can just imagine what horrible things that I would have thought about this movie. It's so overtly sexual and I was 16. Gah, I just feel gross thinking about it. Also, I think I was weirded out by anything that would be classified as LGBTQ+ because no one really took it seriously. I'm giving points to Peirce and company for fighting an establishment that wasn't really ready for a film like this. This, even if it wasn't or is my cause right now, is revoutionary. It's insane to think that this film came out then, let alone now. It's not like we've solved society's problem with that which is different, but we're at least closer to that world than in 1999. This is me toeing a line. When I have my students write persuasive arguments, I want them to argue one side hard. This isn't persuasive and there's way more nuance to this movie than I can just go absolute with. Boys Don't Cry is an important film that is really problematic. I know that I'm questioning that is considered crucial to a lot of people's lives. People's lives are better because of this movie. But I'm watching it for the first time in 2020. This movie wasn't precious to me, so I have to be able to respond to what I'm watching. There are things that are stepping on rights that might not be what the movie is shooting for. The movie is a biography of Brandon Teena, whose tale is extremely tragic. There's no excuse for the things that happened to her happening to anybody. I already want to bail out of the following argument and I feel gross for bringing it up. Brandon Teena was a transgender male at a time when that was unheard of. It was this moment where we couldn't have a conversation about it without snickering or treating transgender people as something akin to J. Edgar Hoover. But Brandon is a troubling character. I can't imagine how hard it is to be someone who is transgender. It seems like a hard world to live in during this society, let alone the '90s. But Brandon is also someone who is more interested in seduction than love. He claims that he is the greatest boyfriend that ever existed and that his significant others absolutely adore him. Why, then, is he not with those people? A lot of what Brandon's life is based on lies, and not objectively great lies. I am completely sympathetic that this lie is a difficult one to tell. Brandon, the real Brandon, probably fell hard for a lot of people who probably rejected him because of the truth of the situation. But Brandon is also offering a false bill of sale. I talked about this moment in Touch of Evil.. PG-13 for some pretty obvious innuendo. I think that's what the MPAA is really looking for. It doesn't feel like a PG movie, so thus it can't be a PG movie. But I'm going to talk about this in what I write: the movie really dances around the idea that his is a brothel. The rules of no-touching are very quickly ignored. Yeah, I think the movie should be PG-13, but maybe not for the reason that it gets. Technically, the movie is all about prostitution without actually saying the word "prostitution." A well-deserved PG-13.

DIRECTOR: Jerusha Hess So my school is among the many that is closed. I have no idea how this is going to affect me. Am I going to get more work done? Am I going to have less time for my blog? I don't know. Realize that work takes priority. I've been actually doing a pretty intense job with my work. I'm actually just using my lunch hour to get this written, so let's see how productive that actually makes me. I'm also really curious to see if my writing style changes knowing that I'm isolated from most of the world. As of right now, the staff is still coming to the building, but my room is pretty isolated and I'm obsessed with cleanliness. Really, things should be alright. I know my wife isn't happy. I don't know if this is the room I'll be in for the long haul, but we'll see. A while ago, to raise money for Australia's wildfires (man, the world is falling apart. I just realized between Coronavirus and just everything being insane that maybe things aren't great out there), students bid on prize packages from their teachers. I decided to donate a free lunch and film club for the auction winner where the student got to pick the age-appropriate movie and some friends to join him or her. Well, we decided to cash that prize in. The only issue...she didn't know what movie to pick. We had just finished reading Pride & Prejudice and went to go see the Cincy Shakes version of the play, so I offered Austenland as an option. While my Viking Film Society tends to be more traditional classics, I realized that everyone in the room would finally get the Jane Austen jokes within Austenland. To skip ahead to the end, it went really well. Does that mean I love it? Probably not. There are times that I remind myself that I'm a film snob. The biggest critique I have of Austenland is that it is just another rom-com given a little bit of street cred because of the Austen wallpaper. As I always do, I really encourage you to enjoy what you enjoy. Romantic comedies really have to be something special to me. I don't know why I don't appreciate this same philosophy with all comedies or all action movies, but romantic comedies really seem to go for a lot of the easy jokes. Jennifer Coolidge is a genius. She's one of the funniest comedians out there. But the movie knew they had her and just depended on her to make the movie funny. She's delivering these lines like butter, but what she's saying isn't all that funny. I think Keri Russell is in the exact same boat. Russell is famous for her role in Waitress, a movie I remember hating that everybody else likes. Admittedly, I was even less cool with rom coms back then, so keep that in mind. It's really banking on a lot of goodwill. Keri Russell, Jennifer Coolidge, Bret McKenzie. That's some good will. But I'm going to give a lot of points to one element of the movie. I love when a formula film disrupts the formula a bit. The Bret McKenzie fakeout is one of the best rom-com fakeouts I've ever seen. I don't think a movie has built up a character with enough good will only to throw it all away in one swift motion. This is the second time I've seen the movie and I was watching to see if it really worked. I mean, it doesn't work great, but it doesn't have any faults with the twist either. Yeah, it's intentionally a misdirection, but that's the point. Like, it tricked me. It did what it was supposed to do. I want to say that is a fault, but it isn't. At all. Sneakiness is fine. If you establish rules that people are allowed to lie and then they lie, that's fair play. I don't know why I love a good fakeout so much. I know I hate bad fakeouts, but that's kind of redeeming to the movie. The Bret McKenzie fakeout is great and I totally support it. But let me talk about the oddest thing in the air. The world of Jane Austen is about courtly manners. It's the Regency Era and Jane herself is a bit of a silly character. It's a rom-com and they have to quickly define her quirkiness. I get it. But there are moments where Jane doesn't seem to understand the rules of Austen. It's like the first tend minutes establish her as this expert at the Regency Era. What did she think that she was going to get? It's absurd that she wouldn't be on board for absolute authenticity. But I've already been derailed... This place is a brothel, right? I mean, we're dancing around it and claiming that it isn't a brothel. But it totally is a place for men to prostitute themselves for women. These women have a very specific fetish, I get that. But the movie starts with the promise that there will be no touching and the characters are constantly romancing one another. It just somehow looks charming. It's really weird that the movie really never addresses this. There are these fantastic moments where we get the behind-the-scenes of Austenland as a location. The actors step out of character and talk to each other from the perspective of the "real versions". But they aren't at all concerned with the fact that they have to sexually interact with these women. Because the movie is PG-13, it doesn't have the characters have intercourse. But there's that montage sequence with Jane. There's a lot more than flirtation going on. Also, the location promises romance for each of the guests. There's a really uncomfortable moment with that thought. It doesn't have romance as an option. It's part of the package (pun not intended). The end of the movie almost creeps that door open a bit, but that leads to the other element that is in the movie... ...Mr. Wattlesbrook. This movie is from 2013. That seems like is pretty recent. It's seven years ago. Remember how I had my high school seniors watch this movie? They were 11 when it came out. For them, this movie seemed ancient and I felt even more ancient when I did that math. It's so interesting to see how much culture has changed in the past few years. It's never been okay to aggressively manhandle a woman, especially in a sexual context. But Jane kind of gets over it way too easily in this movie. I'm White Knighting the crap out of this essay and I acknowledge that, but Jane doesn't really seem all that phased by it. Part of the tragedy is that probably are used to this kind of lewd behavior. But the other end of it is that it is an important plot point for the movie. Jane needs to take it in stride when it happens to keep the romance story going throughout the movie. But she also needs to be sexually exploited so that Jane Seymour can send both actors after her to win her back. She needs to hold a card over Austenland and that's the card they gave her. It's kind of...cheap, that moment? It should be this really important part in the story. The movie has a real moment to provide commentary on society with Jane and Mr. Wattlesbrook, but it is afraid to go up against its subgenre. The movie's tone is frighteningly positive throughout. There's a "woman stepping out moment" that's in slow motion that just completely abandons all sense of reality. So to include this really dark moment kind of gives the message that it's simply okay to be harassed like that. (This white knight comes with a gallant horse and can lord his own morality over everyone, thank you very much!) To compound that, Jane allows Wattlesbrook to get away with it, without retribution. That's an even more problematic ending. She assumes that Wattlesbrook has done this before. She acknowledges that he might do it again. Yet, because she is emotionally distant from the act, she drops the lawsuit. So she's okay with it happening again? It's really bizarre. If Jennifer Coolidge didn't buy the place, would Wattlesbrook continue that act? Also, he's in that credit sequence, so eh? I don't hate the movie, but it also really has this dark element that it is really trying to hide behind Jane Austen. I get why my wife probably didn't love the movie overall, but I don't know how much this movie really does for the Austen fan. Honestly, it's absolutely perfect for people who are just starting to understand Jane Austen and if they understand that there is a whole subculture about her out there. But Austenland really is just another romantic comedy. As far as newer romantic comedies go, it's not terrible. I got a few chuckles in. But on the other end, it's got some problems with it as well. R. I feel like it's been a while since I've written about an R rated movie. Oh, man, this is so exciting. I know I shouldn't be encouraging vice, but it is so much easier to talk about why a movie is R versus why a movie is G. These are small things that you probably don't think about, do you? The language is something else, so I wouldn't worry about that. But there are implied sex acts, smoking, drinking, violence, death --one being a pretty brutal execution. It's a well-deserved R.

DIRECTOR: Rian Johnson Technically, I'm supposed to be writing about Austenland. I try to write in order of film watched, but I want to close up noir week with an homage to film noir. I'm thinking of doing my paper on this. Maybe this will help me get a lot of the loosey-goosey thoughts in words so I can cherry pick an interesting thought. Sorry, Internet, you are my brainstorming page. In college and post-college, this movie was everything. Even though I haven't watched it in ages, there's a lot of beats that I instantly remembered. It's one of those movies that I memorized parts of, but not the whole thing. The insane thing is, despite the fact that I understand 75%-90% of it, there's still a solid section of "What is Brendan doing and why is he doing this?" I'm sure my friends could elaborate, but it is almost trivial. I feel like I get annoying about Brick. It's one of those movies that's a little bit of a deep cut, but also kind of a poser movie. It's what I would talk about before I got the Thomas Video job. I'm being the biggest snob in the world right now, but it's kind of how I feel. The movie, itself, is genius. I love it and I unabashedly love it. I want other people to love it. But I have to be a bit critical, even about the things that I adore. The very conceit unfortunately subjects it to elements of trying-too-hard. It's Rian Johnson's first full length film and it has a lot of elements that kind of feel both a mix of film school and also a bit of '90s indie aesthetic. Perhaps it is the budget. Perhaps it is a bit of eager directorhood, but there are certain things that really pale technically compared to stuff that he would be doing later. But none of that matters. It's totally cool to be a fan of Bottle Rocket or Clerks. Everyone has to start somewhere and Brick is one of those movies that transcends most people's first movies. It's very tight. While it might be a hard sell, the movie beams passion. Every single line stays in the world of the film. The characters are interesting and complex. I have a theory about writing mysteries that may or may not be accurate. If I had to write a mystery, I would write it backwards. What result would I like? Then, I would write the chronological, unbroken narrative...that scene where the protagonist explains the whole mystery. Finally, I would systematically cross out excess information and dump major plot points in non-chronological order throughout the story. I don't think that's what is happening with Brick. Brick seems more challenging. There's something far more deep about Brick. It seems like this was intricately sculpted. There's so much going on with so many levels. For all I know, Johnson used my method for writing, but there's something that acts as a painting withing the movie. It's really impressive. I...am genuinely impressed. Now that I'm knee deep in film noir, though, is Brick a member of the film noir family? Is it an homage to film noir? It might be something else completely. There's this idea that I have beating around my brain that I'm formulating. The language of Brick has the same absurdity as some of the stuff that I've seen in film noir. Whatever can be defined as 1940's slang is accentuated and embraced throughout the film. But with Brick, it is a conscious effort. Perhaps Hollywood was exaggerating the language of the era at the time to create a sense of otherness, but it took the rudiments of the culture and expanded upon it. Brick's active effort to create that sense of otherness is perhaps a commentary on the film as a whole. Perhaps the inspiration was the great moments of film noirs, with the mile a second dialogue that is so laced with idiom that it ultimately lacks clarity, but it almost has a Shakespearean element to the language. There's a line, and I ask for your forgiveness that I don't remember the exact wording, that mirrors "Not where he eats, but where he is eaten." My weird theory is that it all started with an admiration for the jargon of film noir and then it evolved into an appreciation on a Shakespearean level. I wonder if the whole film is a comment on how film noir should be considered high art, not disposable art. The thing that I think I want to challenge is the conceit that is staring me in the face. I've been dancing around this is exclusively film noir element. The conceit is that it is film noir in high school. The real bummer answer would be "it just fits." In the same way that Encyclopedia Brown solved mysteries, I suppose that Brendan too can also solve mysteries. But there's a seriousness woven into the absurdity of Brick. We're both supposed to laugh and hold back from laughter. Someone says the best comedy is that which takes itself seriously. I don't know if that's absolutely true, but the movie treats it as such. So if this film is an homage to the era of film noir, what does the high school setting say about what film noir is all about? My current theory is the idea that there is something developmentally stilted about film noir characters. Focused on their own happiness and neuroses, these characters are moved forward by id and desires of instinct. Listen, I'm not going to slag off high schoolers, at least not all of them. I teach high school and it is irresponsible to lump a bunch of people into one group. But high school is obsessed with an imbalanced sense of empathy. Brendan believes that he is hunting Emily's killer to the ends of the Earth. There's something romantic in both meanings of the word with Brendan's quest. But as much as Brendan claims altruism for his quest, it is an odd narcissism that Brendan is seeking. He is the center of a world of insanity. It's probably why he falls for Laura so hard. It's that odd dynamic knowing that this is a quest for Emily, but he's driven entirely by the obsession with revenge. Emily almost seems distant for a percentage of the film, but that doesn't really seem to matter. Instead, there's an odd almost Viking glory to Brendan's quest. He takes abuse and takes pride in being able to power through a near death experience. Johnson reminds us of Brendan's deterioration through his gag-worthy coughs throughout the film. He's on a suicide mission and it is the kind of suicide mission that only a high schooler can go through. I'm reminded of D.O.A., the absent thought of self-preservation woven throughout the movie. I think I have some rough ideas of what I could talk about. I now have to see if there are scholarly articles on Brick. I'm going to guess that it's pretty minimal, but we'll see. Regardless, there's some really good content here. I'm going to whole-heartedly recommend this movie. It's not encapsulating of my film tastes, but I'm also not ashamed of liking this movie either. Not rated! We don't even have a "Passed" or "Approved" stamp for this movie. Honestly, I don't know what to do now. I mean, it's no different when it comes to saying inappropriate things that happen in the movie. I will say that the most distressing thing about The Third Man is the sick ward full of dying children. You don't actually see the kids, but it is a bit of a horror movie knowing what Harry has done in the name of profit. There's shots fired. People die from gunshot. But really, the movie is pretty quiet, especially considering that I just wrote about Scarlet Street. It's not rated, but it is more about what you don't see than what you do.

DIRECTOR: Carol Reed It's the Orson Welles movie that's not actually an Orson Welles movie. I always associate this movie with Orson Welles, both with performance and with direction. I watched it back in the day when I bought the Criterion of it and then I haven't really revisited it since. But in my head, everything in the movie is Orson Welles. Welles, at best, has five minutes of screen time? Don't worry, I'm not saying anything new. Peter Bogdanovich opens the film with a special guest introduction. With his name-dropping persona, he comments that "Orson" loved stuff like this. It was the perfect role for someone. Everyone talks about the character for the majority of the film and when he finally shows up, his performance is considered genius. I like Paper Moon, Mr. Bogdanovich, but I wish you would just be slightly objective over the whole thing. (Although, is he the director in It: Chapter Two? Probs.) It's actually really weird that I love The Third Man so much. 1) I always mix it up with Touch of Evil, which makes me a bad film blogger and 2) it shares a lot of the same DNA with the Cold War spy drama, similar to the stuff that John LeCarre writes. As much as I find the Cold War fascinating, John LeCarre bores the living daylights out of me. But The Third Man more meets the tone of the Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy stuff more than the rambling jargon of those movies. Really, it takes the best elements from those films and purges all of the nonsense that I find unbearable. A lot of that comes from the unique environment. Vienna post-war is this very specific location. The law doesn't work like it normally would. Like post-war Germany, Vienna is divided into zones. The law works one way in one place. It is a different beast in another. When setting becomes so important to the plot, it kind of offers us something that we're not really accustomed to. The rules not applying almost creates something wholly original. It's a crime that I confuse this movie for Touch of Evil because I actually think that The Third Man might be wholly unique. Perhaps someone out there might be able to make a healthy comparison to another movie, but I'm blanking on anything right now. (Note: I don't feel like rewriting this paragraph, but I am aware that The Third Man is pre-cold war. If anything, this is an ancestor to The Spy Who Came in from the Cold.) I know that it is going to sound like I'm straining to find something to write about, but I'm really not. There's something oddly prescient about The Third Man for today's culture. It seems like low hanging fruit to attach this movie to a #metoo culture, but we're kind of in a world that asks us to question those around us. It's not even that topical to go #metoo, but I do want to make the connection between the two. I was a huge Chris Hardwick fan. I know. That makes me that guy. I listened to a billion episodes of Nerdist for years. I saw him perform live in Montreal and I think his persona is genuinely inspiring. I know that he's grating with his type-A personality, but I'm a guy who has been teaching for a decade, has a blog, runs four miles a day, and used to have a podcast. There's some connection there. But when Chloe Dykstra made those accusations about him, I didn't know what to think. Honestly, I still don't really know the whole story. The old guard within me wants to believe Hardwick. After all, I've been in a toxic relationship where my ex-girlfriend yelled at me for all of the horrible things that she had done. But the other end of the spectrum, it also seemed eerily plausible that Hardwick may be abusive, at least emotionally. The Third Man, despite it's great reveal that Harry is alive the whole time, questions the morally noble concept of loyalty and puts it up against the crime of ignorance: selective blindness. Maybe we're in an era that we have to start questioning everything we do. I had a conversation with my wife about The Outsider on HBO. If my wife had damning circumstances surrounding a murder, I 100% would believe that she didn't do it. But she didn't say the same thing about me. I know that I'm a pacifist, but in a heartbeat she would sell me down the river. The Third Man is this criticism about the role of humanity. Joseph Cotton's Holly Martins is a likable guy, but he's kind of a brute. He's instantly standoffish. He is really to quarrel before he has facts. And he's the likable hero of the whole piece. Anna, perhaps, is the most sympathetic character throughout the story. While technically a criminal, much of her criminality focuses on simply being an illegal refugee in a region that does not want her. Yet, she is also completely allowing actual evil crime to happen in the name of her own selfish love. This is one of those rare films noir that has the police completely moral and justified in their actions. Holly seems like he is fighting for a crusade out of loyalty to a police force that is more worried about conviction and closing books than doing anything actually beneficial to society, but it is really quite the opposite. In a way, Holly is a villain of the piece until the truth is revealed. He becomes heroic not through his investigation, but through his character development. I go through these phases where I wonder if the world is a good or bad place. I may have written about this before and I ask you to forgive me if this is just a broken record. Since I was in high school, I kept wondering if the world is a good place with bad people in it or is it a bad place with good people in it. For the past four or five years, I've lent into the latter. The Third Man kind of confirms this. Harry seems like this really great guy. Everyone seems to like him. But for all of his charisma and relationship with Holly, Harry finds the idea of not profiting off of someone's misery naive. I would like to say it is because Harry is the surprise antagonist of the piece, but this is how the world works. I polled my class if they could take a job where they would be paid remarkably well for doing something they thought was immoral. Thinking that the class would be split pretty evenly, I could then start a debate. There was one kid in the entire room who would refuse that job. I would like to think that they were just bragging and playing a game, but one of my more moral students was woo-hooing the downfall of the stock market. He bet that everything would crash and he just started sweeping up cash. I don't know exactly what he had invested in, but it was the direct result of everything else failing. When I told him that people would probably be suffering because of this crash that he bet on, he didn't really seem to care. This is a kid I completely respected and that I lead in prayer every day. It's a little bit of a bummer because as a humanities teacher, that's exactly what you expect to pass along: humanity. I talk about morals and conflict and the role of man's soul and it seems like that is fighting an uphill battle. So then why do I like The Third Man when it is so depressing to think about? I think addressing the themes that Carol Reed's The Third Man discusses reminds us that we should be like Holly. Holly is a braggart who changes when the facts are presented to him. This is a world that actively distorts facts to match personal bias. Holly really wanted to deny everything that he was hearing, but God forbid, he did a little research on his own and discovered that maybe these reports weren't lies. Maybe our gut might not be the best litmus test for what makes a good person. I mean, the movie by itself is great. If you removed all of the pompous morality that I just dropped, the film holds up beautifully. But it's so weird that a movie like The Third Man is calling out people for unhealthy skepticism. Approved. I wonder what the difference between "Approved" and "Passed" is. While my bet is that it is simply shifting terms from year-to-year, I know that Scarlet Street was banned for on-screen violence and lewd behavior. I'm actually really weirded out that IMDb lists Scarlet Street as approved because I don't think it was allowed to have a wide release. While film noir tends to get violent, most of that is pretty Hollywood-y, slightly cartoonish, or off-screen. The murder in this one is actually kind of brutal. There's also a really graphic suicide attempt and the premise of the movie is about infidelity. It also makes infidelity look a bit sympathetic, despite the fact that everyone gets his or her due in these morality tales.

DIRECTOR: Fritz Lang Guess what, gang? I did my presentation on Fritz Lang just before watching this movie. Mind you, the presentation was on M, so I don't know how much it will help while writing this. Regardless, I feel slightly more authoritative when it comes to writing about Scarlet Street. Again, I'm just as likely to be wrong, but I'll be wrong even more confidently. Fritz Lang is another one of those directors that I get really excited to see pop up as director. I don't think I realized it before, but Lang does a lot of things that he really likes. Leitmotifs, if you will. Doing a presentation on M and then immediately watching Scarlet Street made me a little more hyper-vigilant things like this, but I couldn't help but notice Lang and his use of crowds. Also, his anxiety inducing use of pipe organ might be a little intense. Mathematically, this movie shouldn't work. I know that I enjoyed it overall, but there are some absolutely bizarre choices happening in Scarlet Street. Maybe it's film noir, or cinema in general, that believes in the absolutely insane world of coincidences. I guess this hearkens to theater in general. Storytelling becomes so much more interesting knowing that the long shot is going to pull through. It's just in these consecutive viewings of film noir, I really start to question whether or not fate actually exists. Like Detour, Scarlet Street really rides the whole coincidence train to the station. New York must be the smallest little village that ever existed because anyone who could run into each other actually does. I don't know why this bothers me so much. I think I have a threshold that seems to really teeter on broad skepticism. It's just that there are so many moments where the wrong person shows up at the right time and the story wouldn't really work otherwise. To really stress this point, look at Chris (even his name is admitting to the fact that he will be running into the wrong people at the right time. Chris Cross. Wow.) at the beginning of the film. Chris's life is insanely small. The party that is thrown for him (weirdly set in the past) makes him feel like he is an attendee at his own party. He runs into a cop who happens to be feet away from an assault. Running into this woman, who conveniently mistakes his profession and his level of income sets him down a road to a con job that couldn't be predicted. His paintings, seen by everyone as mediocre, are then the pivotal Macguffin for a series of sales without his knowledge. It's then that a famous art critic recognizes Chris's gift, despite the fact that everyone says otherwise. It's then that this art dealer becomes this amazing detective and hunts down the painter. But not only does he get hoodwinked by Kitty, but that Chris's wife sees the paintings in the art critics window despite the fact that Chris's wife abhors art. Then, the most insane thing, the painting on Chris's wall of his wife's deceased husband foreshadows the return of the husband, who is NOT AT ALL DEAD, which is the get-out-of-jail-free card he's been hoping for throughout the majority of the film? It's all a bit much. That trial in the end is really a reminder that the movie shouldn't really make a lick of sense, but we still have to buy it if the movie is going to progress. Then why do I like it? A couple of days ago, I kind of railed against D.O.A.. I considered it incomprehensible, which made it nearly impossible to appreciate the character development. Scarlet Street doesn't have the exact same problem. I completely understood every element of Scarlet Street. But like D.O.A., it has that one thing that is a glaring problem with the film as a whole. While D.O.A. made no sense, Scarlet Street really borderlines into the almost silly. The odd thing is, again, I feel like it is to tell a fairly simple morality tale in a feature length sitting. I'm not complaining about the runtime of this movie because 1 hr 42 isn't that long of a film. But it also kind of feels like a comic book. Listen, the people who know me know my obsession with comic books. I adore them. I teach with them. I consider them a viable medium. But the glory of the comic book is the episodic nature of the storytelling. Scarlet Street is a character development story that really can shape up over the course of 40 minutes. The movie works perfectly fine at an hour 42. I have no beef with that. It's just that all the silliness that's added to the tale to make it a long movie is what is detracting from the believability of the film. At its core, the story is about a lonely gentleman who married poorly. At this midlife crisis, he meets a girl who makes him feel young again. She takes advantage of him until he ultimately snaps and kills her. It reads very much like the old EC horror stories. It's a tightly contained morality play about appreciating what he has. It reminds society to stay in their lanes and to choose age appropriate relationships. Chris's sin is actually pretty sympathetic in the movie. We get that he has a harpy for a wife who doesn't appreciate his passions. But as Lang and his team really establish, that's his (Chris) cross to bear. The thing that the runtime does allow for is great stuff with the villains of the piece. Dan Duryea as Johnny Prince is so over-the-top it actually is pretty enjoyable. I don't know why I give some people a pass and some people I really harangue about nuancing their characters. I just do. Also, Johnny's absolute insanity throughout the piece really sets up for a great downfall. I couldn't help but notice some parallels with literature that would come up later with the themes, but I love the idea of a guy being used up by someone else and the parasite taking the fall for something he ultimately didn't do. Fritz Lang has his cake and eats it too. Johnny is, despite all he's done, innocent of the crime he's convicted for. But Johnny is such a sleaze and such a criminal throughout, that it's oddly cathartic to know that he has the punishment of death. It's a terrible thing to want, but it is such a great moment. I don't know if this surprised anyone, but we had a debate in class about the more torturous ending. Lang wants us to say that Chris had the worst fate. I don't know, man. Emotionally and logically, I kind of agree with Lang. But the cynical part of me thought that Chris is simply self-flagellating. It's not like Johnny was a good dude. That guy was a spousal abuser and is cool with all kinds of evil. I know. In real life, I'm a pacifist and a Catholic who is all about forgiveness. But from an entertainment perspective, the death of Johnny is truly gratifying. This kind of leads me to the whole EC horror comic element that I was talking about earlier. The end of the movie appeals to that horror element that I like. It's such a tonal and genre shift at the end that it's almost surprising. Yet, the entire movie, with its bizarre coincidences and twists, telegraphs that this movie is a horror movie. It's about an adorable painter (which is some odd casting that really works) and his sheepish romance. But then we have that hard turn and the entire movie makes sense. While I like the romance and the con, the movie really sells itself in the last ten minutes. Honestly, when I think about this movie, I'm only thinking of the climax on. That denouement is painful and perfect at the same time. There's a shot where the door shuts on Johnny and I thought, for sure, that the movie was going to end there. It's so great and it's so definitive. But I wouldn't trade this ending for the real ending. Yeah, it's heavy-handed. I don't care. The rest of the movie is tempered enough to allow a moralistic, apocalyptic ending. At gunpoint, I'd have to admit that the movie is kind of dumb. But there's skill here. The movie is pretty impressive when it comes to making us care for these characters. The way the movie is made speaks to something primal and emotional. Despite the absolute melodrama that is being conveyed here, there's something that makes Scarlet Street something truly valuable. I dig it. I don't care that I laugh at it a bit, the movie is something to be admired. Passed. Another passed. This one seems more violent somehow. Perhaps it's the fact that John Huston is behind the camera. It's not like it's that far off the mark of what other films noir do, but it just kind of feels it somehow. There's a tragic tale of a father on the wrong side of the law. He'll never see his baby again. That's pretty depressing, but I don't know if it specifically falls under any purview of the MPAA. Oh, the gross old man ins into younger girls. You can put that on your list. Regardless, it just seems rougher than its peers. Regardless, passed!

DIRECTOR: John Huston Do you know how exciting it is for me to break out the old LaserDisc player? It's very exciting. Sure, it gets frustrating within seconds because the hunk o' junk doesn't work very well. But when it gets going, it's a really good time. Also, my wife genuinely enjoys making fun of me for the LaserDisc player, so any time it gets to justify its own existence is something that I can consider a bit of a win. I was going to use this movie as an extra credit assignment. The last time I watched it was when I purchased my LaserDisc player almost two decades ago. (If you do the math, you can still see that I had no reason to buy a LaserDisc player, but I'm not going to explain myself to you. I love movies.) The weirdest thing about The Asphalt Jungle is, despite the fact that I've seen it twice --once recently--I have a really hard time remembering what the darn movie is about. Like, I watched this less than a week ago. That's nothing. That's chump change. I tend to backlog my blog articles for longer periods of time than that. But it honestly took me looking through a lot of photos to jog my brain to what it is about. The worst part of it is, both times that I watched the movie, I really enjoyed them. My wife fought sleepiness out of boredom. Giving up her phone for Lent forces her to watch movies directly sometimes. (Although she has a caveat that work stuff is allowed and, basically, every article in the world is about Coronavirus.) But there's something that I can spin out of this that doesn't necessarily let me off the hook, but lets Huston off the hook. Commenting repeatedly that a movie is forgettable doesn't really sell it very well. But the thing that I do stress is the atmosphere and the tone of the whole thing. A lot of the films noir that I've been watching have been pretty great. They tell a story of darkness and evil rooting around in men's souls. People do awful things to one another in the name of selfish preservation. But they all seem restricted to a certain degree. I don't want to make this a competition for best because this is only one element of cinema, but John Huston made The Asphalt Jungle perhaps the most intense and hard-boiled crime movie of the lot. I'm going to use Double Indemnity as the contrast, mainly because it might be my favorite OG film noir of the lot. Double Indemnity rides pretty hard on its plot, as does Asphalt Jungle. But what separates Indemnity from Jungle is the fact that Billy Wilder is kind of playing while he makes this movie. It's remarkably fun throughout. While I completely enjoy The Asphalt Jungle (as I write, the whole thing is coming back to me), it definitely feels like Huston is chain-smoking and drinking his way through the production. There's some kind of angst behind the whole thing. I'll always prefer Double Indemnity, but I can feel the studio over the head of Billy Wilder. Wilder is definitely an artist and Double Indemnity is art, but it is art that needs to make a buck or else Wilder's head is on the chopping block. This is to assume that Huston was any different. It just feels like The Asphalt Jungle has a devil-may-care attitude towards filmmaking. The lighting is so harsh and the contrast is so intense. I'm flashing to that scene with James Whitmore in his diner. The diner is perfectly clean. There's nothing out of place. But the overhead lighting acts as an interrogator for everyone who walks in. It seems unpleasant, as does most of the film of Asphalt Jungle. That's probably why Marilyn Monroe seems shockingly out of place. Huston was known to be a bit of a man's director. I don't say this with a point of pride, but the guy loved what he loved. He hardly had time for femininity or vulnerability in his pictures. Instead, he touted up the rugged persona of the patriarchy and flew that flag as hard as he could. But there's something so tragic about The Asphalt Jungle. The movie almost telegraphs the downfall of all these characters. Normally, I'm used to seeing the people who have the greatest falls have the highest highs. While it's hard to really nail down the protagonist of this film, I have to go to Dix because the movie almost tells me that I have to. Dix has the least character motivation. He's almost a protagonist because he has Jean Hagan working as a foil. We sympathize for her, thus we sympathize for Dix. He also begins and ends the movie, so that probably contributes to the whole affair. But Dix is never that great of a guy. It's really weird that Hagan's Doll is into him. He has no redeeming features. He gambles all of his money away. He treats her like dirt, but he's the protagonist. The movie really only alludes to his dream to escape in the latter half of the movie. It's almost like Huston is setting up the whole escape to be an ironic death for him. There's the image of his face in the grass as the horses graze around him that mockingly laughs at the idea that this character ever deserved a minute of joy. And that's almost the purpose of the film as a whole. It's pretty common to see that the antiheroes of these films get their comeuppance. It was part of the standards and practices of the era. If you committed a crime in these movies, you needed to have some kind of punishment for your actions. It's the rules and it makes sense. But Huston, instead of rebelling against an era that was strict about morality in film, decided to ride that notion as hard as it could go. Everyone in this movie is absolutely horrendous and they all seem to be competing for more ironic end. Heck, they aren't even that ironic. They're just mercilessly tragic. It's a little torture porny. But, like, in the best way possible. I suppose that I should add suicide to the list of ways that people die in the MPAA rating, but I didn't think of it and now it has greater impact. The odd thing is that The Asphalt Jungle has one of my favorite plots, despite the fact that I kept on how utterly forgettable it is. The thing about film noir is that it always seems to be surrounding the idea of a collapse of a morally ambiguous man. This movie takes full on pride in the immorality of its characters. In the dumbest connection that I can make, The Asphalt Jungle is the much more tragic precursor to Ocean's Eleven. There's a complexity to the heist. I think I'm just getting used to crimes kind of happening off screen that it is oddly refreshing that we get to see the beat-for-beat heist actually happen. And the weirdest part is that the most likable character in the movie is the perviest. Imagine Danny Ocean if he was into little girls. That's a weird choice. The movie presents Doc Erwin, a German geriatric in a post WWII America, as the most sympathetic character. He's the archetype of a man who has clear genius, but has been robbed of the opportunity to truly be something. Every scene with Doc Erwin reminds us that he's the smartest guy in the room, yet he is manipulated and handled. And he kind of knows it. It's this depressing element that forces us to empathize with him. It's because he's our grandfather. There is a void when it comes to likable characters, with the exception of Jean Hagan, who doesn't really have a meaty part in the movie. But then the movie throws in this really toxic trait. Is it because we know that he has to have his just reward for his evil actions? I mean, I just said that John Huston really wanted to torture these characters. The character has two choices: 1) we could avoid that weird fatal flaw of liking younger girls (we're not talking kids, but teenagers...which is still gross especially when I write it). He goes to prison and that might be the most uncomfortable ending. Or 2), we need him to go to prison, so adding the fatal flaw makes it okay for us to understand that Erwin deserves what he got. It's an odd shift because before this moment, we are kind of rooting for the amoral gangsters to get away with their deeds. Perhaps, to align with the standards for the era, that had to be an element of disdain for the actions of the film. After all, there is a seductive appeal to watching the misdeeds of others. That's what the censors are genuinely worried about. It's silly, in retrospect. But then again, people actually admire the Joker and the Punisher, so they might have a point. The Asphalt Jungle carries with it a great street cred that I keep remembering as I flip through my LaserDiscs. It's a pretty fantastic film noir and oddly is a standard for a lot of films from that era. I don't know why it's not on the syllabus, but I own it so who cares? Passed. But that being said, it's a movie NAMED Gun Crazy. Both of those words in isolation are problematic. Together, I mean...watch out. There's some theft, juvenile delinquency, high speed chases, peril, and straight up murder this movie. Some innocent people just get point blank shot. Admittedly, it's 1950. The concept of skull shrapnel isn't a thing and, by today's standards, the violence is remarkably tame. But there's all kinds of gun craziness contained in an hour and twenty-seven minute movie. But who am I to deny the value of Gun Crazy. It passed!

DIRECTOR: Joseph H. Lewis Status: Still in Facebook jail. I managed to make a makeshift shiv out of memes and anti-vaxxer propaganda. I don't know if I'll ever see the light of day. I write to maintain my sanity. But how can someone keep their sanity when everything is so...Gun Crazy? Gun Crazy wasn't originally a lock on the syllabus. It was up to a pair of students to choose which movie in the pile was going to be the next film assignment. Let's be honest, I was really jazzed that they picked this one because it sounded the most bonkers out of the group. Yep, even more bonkers than the absolutely insane D.O.A. But with all this being said, I really want to establish my personal politics because I'm going to be talking a lot about guns in a movie entitled Gun Crazy. I'm a pretty intense pacifist. If I can get through this life without ever having to cause another person harm, that means I've won. I'm pretty anti-gun. I have fired weapons, but really find no joy in it. If you confront me on my gun politics, I will get mad and then I'll get depressed because I think that the world is a terrible place. There. It's all laid out for you. Don't be surprised if I go anti-gun later. Gun Crazy might be one of the dumber movies that I really like. Listen, I came out swinging and that's a pretty big step for a pacifist. I know. It's easy to call something dumb. I'm sure that one could defend the genius of this movie, but it's pretty dumb. Title wise, you can't really sever the ties between Gun Crazy and Reefer Madness. They both kind of have the same purpose. They're morality tales that actually are far more interesting as entertainment than steering people away from lives of crime. With Gun Crazy, the first ten minutes establishes a very different film than the rest of the movie. The conceit of the film is that the protagonist has ze goon kraziness [I refuse to give you more insight into that spelling] He can't help it. (I really want to break that down later and criticize the whole 1950s for their heteronormativity). He just needs guns. As such, he gets really good at using guns. Now, what I find interesting is that the character really doesn't want to kill. After killing a baby chick --which by-the-bye, has to be a real baby chick because that's how things were done back then --he vows never to kill a living creature again with his sweet shooting skills. I mean, this guy is a crack shot. He can hit anything anywhere anytime. He's very good. That's a cool character choice because the beginning reads like NRA propaganda. (It's not. It's a complete misdirect. It doesn't mean that I wasn't uncomfortable for the whole beginning of the movie.) So his trajectory is that he becomes this professional crack shot. Surely, that will matter in the story later on, right? Nope. The boy grows up, becomes a sideshow act for his amazing gun skills and those gun skills are used precisely once. When Bart goes on a crime spree, he uses that marksmanship to shoot out a tire just once in the entire movie. The first ten minutes shows him doing all of this insane gunplay, but he never uses it once the inciting incident happens. It's bonkers. Why have all of this setup? I'm really playing devil's advocate here, but is it to show that even the most knowledgable gun owner will go off the rails and enter a life of crime. (Please note: despite my very anti-gun stance, I do not believe this and cannot believe that people would believe this.) Most of what I'm going to talk about is the first ten minutes because I...I just can't. It's so much. Like, it's Mystery Science Theater much. The rest of the film is a completely watchable interesting film noir, but the tone and the logic of the first ten minutes is mind blowing. The movie's opening is that Bart, as a teenager, throws a brick through a hardware store window to steal a revolver. We get an understanding of why Bart NEEDED this gun from the store window through the testimony of his sister. I wonder if the movie is commenting on the fact that a boy needs a father to be raised with a sense of absolute right and wrong, but we'll move beyond that. He kills the chick as a child, like I said. He avoids killing a mountain lion despite the fact that it is probably going to kill some poor picnicker down the way somewhere. But the biggest insane moment is the fact that Bart loses is initial sidearm because he was showing it to everyone at school. I'm going to step back and acknowledge that I'm putting 21st Century progressive morality over 1950s conservative America. It's really unfair. Bart lived in a time where a rural school would be a place where a gun wouldn't set off the alarms it does today. But there's this shot...oh this shot! There's a shot of Bart completely surrounded by young school children as he pantomimes firing the gun like the Lone Ranger or something. It's too much. Like, my brain can't handle it. He gets his gun taken away as a low-key punishment. It's the equivalent of me catching a student with a cell phone in my class. So his brain goes into theft mode immediately. He's so driven by the need to continually possess a firearm that he HAS to break into a hardware store. And the nutty part is that is Bart's pretty much only defense. It wasn't his fault, according to his family, because he had his gun taken away. I mean, thank God that the judge thought that argument was nonsense, but it's still insane. But this isn't even the most crazy scene in the movie... I try to keep this page FREE OF ABUSE AND VULGARITY (despite what an anonymous Facebook user submitted), so I can't tell you about the Behind the Scenes of this moment. I encourage you to Google "Joseph H. Lewis Gun Crazy" and find his direction for actor John Dall with the scene I'm about to talk about. When Bart gets out of reform school, he goes to the carnival and is really turned on to a marksmanship exhibit. I don't know why I called it that. It's trick shooting. Peggy Cummins plays femme fatale Annie Starr, who is also a crackshot like Bart. He instantly falls in lust and competes against her trick-shottery. Now, the game isn't target practice. Each person takes a turn wearing a crown with candles. The goal is to SHOOT THE FLAMES OF THE CANDLES OUT without ruining the candle and / or MURDERING THE OTHER PERSON. Now, suspension of disbelief says that Bart could let Annie shoot at him. After all, she is a pro. We see this stuff in magic tricks all the time. But the thing that I can't wrap my head around, no matter how much I lie to myself, is the fact that ANNIE ALLOWS BART TO SHOOT AT HER. Remember, from her perspective, he's a random audience member trying to make $50 bucks. We know nothing about his skills. More than likely, he's not as good a shot as her, let alone better. Yet, this stranger fires at an expert with the assumption that he won't kill her. This entire article is just therapy! I could talk about the feminization of the male protagonist. I could talk about toxic relationships. I could break down the femme fatale. But I won't. Nah, I only care about the absolutely insane first ten minutes of the movie and how it fits, in no way, with the rest of the film. My recommendation: prep for a hilarious first ten minutes and then settle in for a pretty fun Bonnie and Clyde style crime spree that's pretty entertaining. PG-13. I guess this one was reviewed by the MPAA retroactively, but it also makes my job way easier in this section. Touch of Evil is actually pretty intense for an older film. I mean, it's 1958. It's not that old and the roaring '60s are around the corner. There's a lot of content that could be considered pretty offensive. There's on-screen murder, involving one character's eyes bulging out. There's an implied gang rape. A character is forced to use drugs. Also, and this is more of a cultural thing than anything else, there's a pretty intense use of makeup to change races. I don't know why I'm dancing around this: it's pretty close to blackface and I want to say that with the full severity of the term. While the actors don't play stereotypes and aren't in makeup to be laughed at, it's still really uncomfortable. Regardless, PG-13...

DIRECTOR: Orson Welles So let me tell you the State of the Union on this blog. Most of my publicity comes from Facebook and Twitter. Someone decided to flag me as abusive spam. That's fun for me. So the big thing right now is that I feel like I'm writing to the void. I don't think I have a following enough to have people bookmark my page, so we'll see if I can break through the void. It is really hard to write this on a daily basis. While overall it brings me joy, I am really an incentive based person. Sometimes, I need a carrot dangling to get me to be productive. I realized fairly recently that I don't give myself a lot of downtime. My self-care has to be positive and active. The two things that I do for me are writing and exercising and it's hilarious that I don't love doing either while they are happening. I just feel good after I exercise and I feel accomplished after I write. (BTW, when do I watch movies? While I exercise. Ouroboros.) Anyway, I might have a lot to say about this movie. For those people who have been following, this week is film noir week, mainly because I have to catch up on all of the things that I watched for my film noir class. The kicker on this one is that Touch of Evil is the film I'm presenting on, so I have done way more research on this movie than I have for other films. I watched the movie, then watched a commentary for another cut of the movie, and then read a whole bunch of books on it. A lot of the writing I do about movie is me shooting from the hip. When you write about a movie every day, sometimes you have to cut a little bit of the fat from the writing. It can't all be quality. But there's something remarkably soothing about low-stakes writing with my other movies. If I'm wrong, then I'm wrong. No big deal. But there's something absolutely exciting knowing that you have the right interpretation and that there's a whole bunch of evidence backing you up. But given all that, I want to talk about something that none of the things I researched talked about: the look of the movie. Part of this probably comes down to tone. But there's something about Touch of Evil that feels akin to a low budget beach movie. I know it's not a low budget film. Charleton Heston called it the greatest B-movie ever made, but it's definitely not a B-movie. Instead, it just didn't get the publicity that it deserved at the time because of Orson Welles and his reputation as being a difficult director to work with. It's just that the way that the camera moves. Welles loved have a kinetic camera and it shows in his other films. I know that cinematographer Russell Metty was an absolute genius with a camera and a crane shot. After all, I've shown the opening of Touch of Evil to every film class I taught. But the rest of the film is absolutely bananas, and I say that in the best way possible. It takes a little getting used to, but the movie looks and feels more like Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!than anything that came out of the film noir era. It's really nuts, but I really dig it. If there's nothing else to say about Touch of Evil is that it just feels gutsy. Welles is acting as a guerrilla filmmaker despite the fact that he is an expert at his craft. There's nothing really safe about this movie. It's 1958. It's not the first movie to be critical of Americans openly, but it definitely is a pioneer when it comes to that distinction. I'm probably never going to write amazing things about Charleton Heston, not out of a political stance or anything like that, but more out of he has just never really impressed me all that much. But Heston kind of works in this role. Because he's not even attempting to do an accent or a dialect, but rather just being Heston in uncomfortable racist makeup, it kind of gets forgettable. But the hero of the story is the Mexican and the bad guy is the American. That's pretty insane. It's calling the U.S. on its casual racist history while, somehow, making the villain also somewhat sympathetic. Welles hated everything that Quinlan stood for. The movie is openly criticizing the way that police were working in the era. While border police were getting results, they were cutting corners and entrenched in a bias that they could no longer see. He deals with a drug epidemic in a pretty hilarious way by today's standards, but acknowledges that there is a drug problem. It seems like such a risque movie compared to all of the other film noir entries that I've watched. (Admittedly, there's some debate whether or not Touch of Evil technically counts as film noir, so there's that.) It's just that with all of the other entries in this class I'm watching the crime is always kind of ambiguous. We know that someone is evil because they're sitting in a well-lit basement bemoaning the police and stuff like that. We often deal with the consequence of crime and not the actual crime itself. But Touch of Evil really lets us see that crime is happening. Uncle Joe is this heavy who keeps pressuring things his own way. We get a rowdy gang that drives Mrs. Vargas insane. This is a world of chaos and it is really interesting to see it play out. There's two elements of the movie that I absolutely adore. (I'm actually finding this harder to write than I care to admit because I like the movie so much. When a movie is simply okay, I can write page after page. I just hate gushing.) It's a bit on the nose because those two elements are the things that Orson Welles set out to accomplish. The first thing I adore is the relationship and downfall of Quinlan. Quinlan is a great villain. He's so good because he knows that he's the hero of the story. He's a guy who keeps shifting his moral code by an inch time-and-time again. Touch of Evil is a look at a man who has moved that line so many times that by the time we meet him, he's morally kind of bankrupt. Yet he holds onto his victories and his morals as justification for all the evils he does. I love that Quinlan starts the film as a recovering alcoholic. He's gotten fat on candy bars, which makes his girth indicative of a man who has just given up. But he uses that sobriety as a high horse. It's this double effect of pride in failure. It's really excellent. Yeah, the movie goes "Demon in a Bottle" on him when he returns to the booze, but it explains so much about his character. Similarly, and this is kind of gross on my part, I really find the whole B-plot of Mrs. Vargas interesting. For someone married to a higher up in the Mexican police force, her choices in the film are a bit bizarre. I don't think that Welles is commenting on the ineptitude of women, at least I hope he isn't. But she starts the film with such agency. She chooses not to define herself by her husband. She addresses a threat to their domestic bliss by accepting the invitation to meet Uncle Joe. It's just that we, as audience members, quickly recognize her mistake. As gross as it is from today's standards, watching Janet Leigh get flung into the insane criminal underworld is haunting. I think I know why I like it so much and it doesn't really let me off the hook. Janet Leigh's portion of the movie is a horror film. She's completely overwhelmed by her situation. While there's no blood or death, she's tortured throughout the film and we want to see her as the final girl get revenge on those who tortured her. I'm also a fan of bummer endings, knowing that everything doesn't quite work out for her. She gets a bittersweet ending, freed from the torture of the gang. But the gang continues to live on, without justice being brought to them. One of the things in the commentary blew my mind. There's a really weird performance in the movie that I instantly made the connection to Anthony Perkins' Norman Bates. Dennis Weaver plays the night manager of the motel and his performance is insane. It was clear the archetypal connections between Norman Bates and Touch of Evil's night manager, mainly because they serve the same role in the film and are also very clearly insane. There's something in the costume, too, that Hitchcock may have picked up on. Perkins is genius in his subtlety of Norman Bates. Weaver is an acid trip. But I didn't exactly make the really obvious connection that Janet Leigh is the one being tortured in a hotel room by a Norman Bates type. I'll talk about it in my presentation, but I can't believe I didn't pick up on this. Hopefully, I'll get out of Facebook jail soon once it is reviewed. But until then, I will yell into the darkness until I get too depressed to write anymore. Touch of Evil is definitely worth a watch. It's a little weird and can get a little tedious at times, but it absolutely is a work of genius. Approved. It's about a man knowing he's going to die in the next few days, so death is a common theme here. There's a sniper at one point. I don't know if we ever really feel the horror of what it would be like to be under sniper fire or the moral ambiguity that would accompany that with a movie like D.O.A., but I can't deny that it is in this movie. Also, the movie treats adultery pretty casually. The sin that the main character commits is that he has a weekend where he wants to cheat on his girlfriend and she kinda/sorta gives him a free pass. Regardless, the movie is pretty tame. Unless you have a mental trigger when it comes to the sound a slide whistle makes, you'll probably be fine.